The Vulture

Authors: Gil Scott-Heron

THE VULTURE

GIL

SCOTT-

HERON

THE VULTURE

Grove Press

New York

Copyright © 1970 by Gil Scott-Heron

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author's rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003 or

[email protected]

.

First published in the United States in 1970 by

The World Publishing Company

First published in Great Britain in 1996 by the Payback Press

an imprint of Canongate Books Ltd, Edinburgh

This edition originally published in 2010 in Great Britain

by Canongate Books

Printed in the United States of America

Published simultaneously in Canada

eISBN-13: 978-0-8021-9392-6

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Distributed by Publishers Group West

12 13 14 15 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Mr Jerome Baron

without whom the ‘bird’

would never have gotten

off the ground.

Standing in the ruins of another black man's life.

Or flying through the valley separating day and night.

‘I am Death,’ cried the vulture. ‘For the people of the light.’

Charon brought his raft from the sea that sails on souls,

And saw the scavenger departing, taking warm hearts to the cold.

He knew the ghetto was a haven for the meanest creature ever known.

In a wilderness of heartbreak and a desert of despair,

Evil's clarion of justice shrieks a cry of naked terror.

Taking babies from their mamas and leaving grief beyond compare.

So if you see the vulture coming, flying circles in your mind.

Remember there is no escaping, for he will follow close behind.

Only promise me a battle; battle for your soul and mine.

The Bird is Back

It would not be much of an exaggeration to say that my life depended on completing

The Vulture

and having it accepted for publication. Not just because it placed more money in my feverish hands than I thought I might ever see at one time, but also because I had bet more than I had a right to on that happening and it was such a long shot.

In 1968 I was a second-year college student at Lincoln University in Oxford, Pennsylvania. I had put up all the money I had earned plus a small grant from the school to follow up what had been a less than scintillating freshman year.

Six weeks after school opened I quit. I dropped out. The reason was the same one that had brought my first year crashing down around my ears. I had an idea for a novel and wanted to write it. I thought I could find the proper rhythm and could balance my schedule between class-work and work on the story, but there was no way. I was getting nothing done. There's a story I heard once about a jackass that was set down squarely between two bales of hay and starved to death. I was just like Jack. When I opened a textbook I saw my characters and when I sat at the typewriter I saw my ass getting kicked out of school for failing all my subjects.

What I asked the school for was similar to leave of absence. I would remain on the campus for the rest of the semester since I had paid for room and board, but I would be at work on the novel and would receive I (Incomplete) for all my final grades. The advantage was that when I finished the book and if I wanted to apply for re-admission to Lincoln or elsewhere, I would not have a complete set of failures to overcome.

The Dean reacted as though I had taken leave of my senses

and asked me to get the school psychiatrist to approve. That read like a challenge and perhaps a bit of ‘C.H.A.’ by the Dean. (In traditional institutions when someone makes a request for extraordinary consideration the person responsible for approval likes to ‘cover his ass’.) The Dean must have thought I was crazy. It certainly seemed crazy that someone as poor as I would bet his last money on a first novel.

My plan was to finish the book before the second semester began in February. That showed how little I knew about what I was doing. By January I had little more (that I felt good about) than I had when I saw the psychiatrist in October and gained his approval. And I still had no ending for the damn thing.

January brought me the idea for the ending I needed and a method of connecting the four separate narratives to the book's opening. Now all I needed was a chair and my typewriter.

That was damn near all I had. Over the next two months I worked in a dry-cleaners about a quarter-mile from the school. The owner and his wife both needed to work elsewhere and wanted someone to mind their property. I slept in the back and took meal money from the small income generated by the students.

The miracle that got

The Vulture

accepted by a publisher, along with

Small Talk at 125th and Lenox

(a volume of poetry published simultaneously), consisted of a series of cosmic coincidences and intervention by ‘the spirits’ on my behalf. Let it suffice to say that the interest in the book of three brothers at Lincoln I will never forget; Eddie ‘Adenola’ Knowles (a percussionist on four of our first six albums and founding member of The Midnight Band), Lincoln ‘Mfuasi’ Trower (Eddie's roommate, who also missed a good deal of sleep as they sat up reading the manuscript instead of doing their school work), and Lynden ‘Toogaloo’ Plummer (my best customer at the cleaners who never failed to sit down and read a few pages when he came in with his things). Those three

friends probably have no idea that they were the barrier that saved me from being pulled into the discouraging blank pages that I faced occasionally when a scene or an idea about the plot, the characters, the connections, something, would not work. I will always owe them.

I must also say here that I came from a family that zipped through college much like high school and kindergarten. My mother and her two sisters and brother all graduated from college with honors, literally at the top of their respective classes. I set quite another precedent by being the first one of their line to ('Ahem') ‘take a sabbatical’.

To say the least it was not a popular decision but my mother had faith. In a telephone conversation we had after the deed had been ‘undone’ she said that she ‘

didn't think it was the best idea I'd ever had‘

but to

‘go ahead and finish it and promise that, whether it was published or not, I would go back to school somewhere afterwards and get my degree.‘

She finished by saying that

‘I would always have a home with her and that she loved me.’

I did not dedicate

The Vulture

to my mother. I dedicated

Small Talk at 125th and Lenox

to her instead because she always appreciated the poetry so much and helped me with lines and ideas (including the punch line for

Whitey on the Moon

).

And there was a special man, a very gentle man, the father of a high-school classmate of mine, who was the person I believe ‘the spirits’ helped me connect with somehow.

I did go back to school. I have a Master's degree from Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore that was sent, sight unseen, to my mother upon my completion of the work, and I have since dedicated many accomplishments in my career to the person who brought me no further grief at that time of stress and need for a kind word, Mrs Bobbie Scott Heron. She is a helluva person and a good friend.

I hope you enjoy

The Vulture

as much as I enjoyed the thrill

of writing it. My experience of putting it together was my way of doing the high-wire act blindfolded, knowing that if it didn't work, if it wasn't published, there was no safety net that I could land on and no hole that I could crawl into, no way to face the other folks at Lincoln and no money to go anywhere else. In retrospect, I think it has held up remarkably well.

The major task of a murder mystery writer is to conceal the identity of the perpetrator while not getting caught yourself. It's a bit like a puppet master who must not be seen pulling the strings.

I admit that as a 19-year-old I had never put on a puppet show in my life. I knew that I was controlling the characters connected to each other. I knew that as the story progressed I had to advance the reader toward the identity of the killer(s), but not that each revelation had to shed new light on all of the suspects.

I was also caught in a language and culture trap. I was writing a story for anyone/everyone to enjoy and guess about as they read, but my characters and their way of speaking and language had to be true to the neighborhood and the murder had to be true to the underworld culture and its symbols.

The Vulture

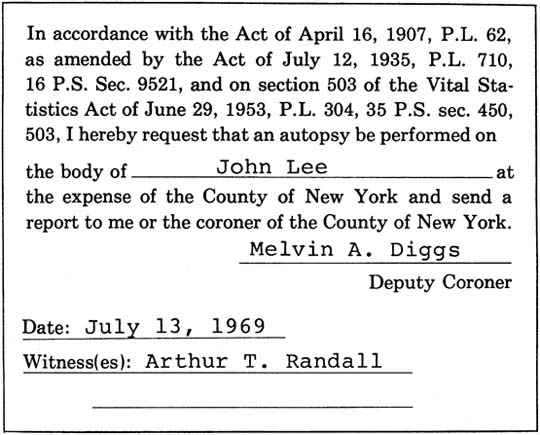

might work as well (or better!) on film as it does on the page. My biggest problem setting it up was how

to show you

the murder of John Lee without showing you the murderer. Hence, the autopsy report in the opening section.

Some people accused me of using that and a half dozen other devices as ‘red herons’. Why they are so adamant about that is ‘a mystery to me’.

I do hope you enjoy ‘bird watching’.

Gil Scott-Heron

New York, September 1996

Phase One

John Lee is dead

July 12, 1969 / 11:40 P.M.

Behind the twenty-five-story apartment building that faces 17th Street between Ninth and Tenth avenues, the crowd of onlookers stared with eyes wide at the bespectacled photographer firing flashbulbs at the prone body. The hum of conversation and the shadows of the rotating red lights cast an eerie glow and kept the smaller children tugging at their mothers’ cotton dresses.

From the apartment windows high above the ground, faces with no visible bodies scanned the darkness and listened to the miniature confusion below.

A young white policeman stood next to the curb leaning into the patrol car, ear to the receiver, listening to the drone of the dispatcher. Suddenly he placed the receiver down and yelled something to the photographer, who cursed and yelled that he

was

hurrying.

The police ambulance driver stood next to his wagon and chatted with a second officer, a kinky-haired black, waving occasionally at the body. The two ambulance attendants, both in their early twenties, sat on the hood of the prowl car smoking cigarettes.

‘You through, Dan?’ the white officer asked the photographer.

‘Keep your shirt on,’ came the irritated reply.

The crowd of passersby inched closer to the corpse, trying to get a better look. Here and there women turned their heads and shielded their children’s eyes as they noticed for the first time the red ooze that trickled from the base of the skull.

The photographer limped away muttering, and the wagon attendants moved in with a flexible stretcher. With some

difficulty they hoisted the bulky frame of the deceased onto a hammock-style death rest and pulled a sheet over his head. Then they loaded their cargo into the van, and within seconds they were whistling down the block toward Eighth Avenue.

The black policeman was asking questions of the group of pedestrians and receiving negative replies to all of his inquiries. He walked back to the patrol car and slid in under the wheel.

‘What do we have?’ his partner asked.

‘Nothing but the wallet.’

‘What about the woman who found the body?’

‘Nowhere to be seen. She’s prob’ly somewhere pukin’ her guts out.’

The prowl car lurched toward Ninth Avenue. The whine of the siren bit into the heavy silence of the night. The neon midnight beacons summoned the restless for beer and whiskey. The youngsters, knowing the Man as they do, followed the prowl car’s progress up the avenue with suspicious stares.

‘Does the name John Lee mean anything to you?’ the black finally asked.

‘No,’ the rookie replied. ‘I donno what to think.’

‘I know what you mean. At first I thought some junky had taken another overdose, but when I saw that blood comin’ out the back of his head, I figured somebody did him in . . . But he wuzn’t robbed.’

‘Shit!’ the rookie exclaimed. ‘I don’ give a damn. It’s outta our hands now. Let the others worry about it.’

‘Yeah. But these Puerto Ricans piss me off.’

‘What?’

‘Talk a mile a minute all day an’ cain’ answer one simple question for me.’

‘They got so many junkies they probably identify.’

‘We oughta bury ‘um all in the gutter.’

‘Can’t.’ The young white laughed. ‘Against the law to bury a man at home.’