The Rape of Europa (83 page)

Read The Rape of Europa Online

Authors: Lynn H. Nicholas

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Art, #General

It was a big dump. A man was splitting small logs on the head of a grey stone twelfth-century Tiger. Further on two goats jumped around two more stone faces which peered demon-like out of a pile of half rotten straw. Next to this in a pig sty was a big Chinese bronze drum full of manure.

63

He had arrived just in time, for the woodcutter had planned to drag away the “junk” and throw it in a lake. (Reutti wondered to himself what theories of intercontinental trade this might have inspired in future archaeologists.) Baron von der Heydt had trouble getting the things to Switzerland, where he had taken up residence since the war, but the East Germans finally surrendered them in exchange for two butter knives and a tea glass and strainer which had once belonged to Lenin. Reutti was succeeded by searchers of equal passion such as Klaus Goldmann, curator of the Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte in Berlin, who spent years on his particular obsession, the location of the Trojan gold. Not until 1992 was that mystery solved by the revelation that the treasure did indeed go to Russia in 1945.

After the mid-fifties the question of Nazi loot was no longer of great interest except to museum professionals and dispossessed owners, though sporadic finds and returns did cause little flurries. The two tiny Pollaiuolo panels from the Uffizi entitled

Hercules Killing the Hydra

and

Hercules Suffocating Antaeus

, which had been unaccounted for in 1945, turned up in the hands of a former Wehrmacht soldier who had emigrated to California. The Soviet Union returned most of the Dresden and Berlin collections to the German Democratic Republic in the late fifties. In 1955, with the help of Miss Hall at the State Department, the Czartoryski family, after threatening a suit, got a cash settlement for two of the medieval enamels they had hidden so long before in Poland. The pieces had been sold to the Boston Museum by Wildenstein, who had found them in Liechtenstein. It was not an unfriendly arrangement; afterward, the Czartoryskis and Wildenstein joined forces in an attempt to trace their missing Raphael, which the Metropolitan wished to buy. But this effort, alas, came to naught, and the picture remains lost.

64

For a long time there was little further news of the fate of missing objects. In Washington, Miss Hall and her successors toiled away on cases of theft by military personnel and whatever else came to their attention. In Austria, several thousand unidentified works languished in the monastery of Mauerbach until their presence was revealed by

ArtNews

reporter Andrew Decker in 1984. And in all nations, most of the records relating to confiscation and recovery lay classified and often sealed for terms of fifty years and more. The United States Army retired and then destroyed files on which there had been no action for a number of years, among them the one relating to the unsolved theft of church treasures from the small East German town of Quedlinburg.

This was too bad, for after decades of silence rumors began to circulate that certain objects from the treasure were being offered for sale in Switzerland. Joe Tom Meador, the light-fingered GI, had died in 1980 and his sister and brother had inherited the objects. They then seem to have sold a number locally. Their lawyer, more sophisticated, felt that the objects might bring more on the New York market, and had the gold and jewel-encrusted

Samuhel Gospels

appraised. The heirs were stunned to discover that this piece alone might be worth upwards of $2 million, but deeply disappointed when the appraiser also told them that it was probably stolen and therefore unsalable. Despite this advice, in the next few years they sent out feelers to dealers and museums. The Getty turned them down, as did Sotheby’s. One Paris dealer who was willing to play offered the

Gospels

around Europe at the exorbitant price of $9 million.

By now rumors of the availability of the manuscript were spreading

nicely. In Washington, Willi Korte, a free-lance German researcher who had done considerable work in the American archives for Klaus Goldmann in his efforts to trace the Trojan gold, consulted an American lawyer, Thomas Kline, for advice on how to track down the owners and retrieve the treasure. But in 1990, before he could find them, news came that an entity called the German Cultural Foundation of the States had bought the

Gospels

from a Bavarian dealer for $3 million, of which two-thirds was paid to the Meadors on delivery. The Bavarian had acquired it in Switzerland, and was secretly negotiating the sale of a second Quedlinburg object through the same channels.

A sale of this magnitude inevitably attracted press attention, and William Honan, covering the story for

The New York Times

, began his own investigation to identify the sellers. It did not take long. As soon as their names were published, Meador’s old Army friends began to call Honan to report that they well remembered that Meador had taken the Quedlinburg objects. A little research in the Army files revealed his hometown. Korte and Kline rushed to Texas to try to negotiate with the family. After first agreeing to let the duo photograph the remaining objects and put them in a safe place, the Meadors suddenly changed their minds. Kline, by now representing the Quedlinburg Church authorities, obtained a restraining order which prohibited removal of the pieces, but in the meantime two more vanished from the bank.

The German Ministry of the Interior and the Cultural Foundation, who had not previously known the identity of the sellers, now offered to negotiate a settlement. In the end the Meadors got $2.75 million for the objects still in their possession. The German Cultural Foundation, which had been prepared to pay far more, did not wish to bring charges against them and even allowed a fancy little show at the Dallas Museum of Art before the ancient relics returned to a newly installed treasury at the Quedlinburg Church. The U.S. government was less relaxed: the Meadors will now have to deal with the IRS and possibly the FBI. Though many deplore this paying of “ransom” for stolen goods, the whole affair has had the salutary effect of inspiring a number of other ex-GIs or their families to turn in things they “found” during their duty overseas.

65

The search for missing works of art still goes on. International law enforcement agencies and private foundations such as the Institute for Art Research in New York keep an eye on the markets. The reunification of Germany and the raising of the Iron Curtain have led to the renewal of investigations all over Europe. In the now accessible areas of eastern Germany, treasure hunters and adventurers scour long-sealed passages and

remote caves, hoping to find the Amber Room or see the gleam of gold. The French Foreign Ministry has retrieved Rose Valland’s papers and is busily perusing them at the Quai d’Orsay. Scholarly groups in Germany and Eastern Europe are attempting once again to list losses, while the Russian and German governments are negotiating the still politically potent issue of restitution of objects held by their respective nations.

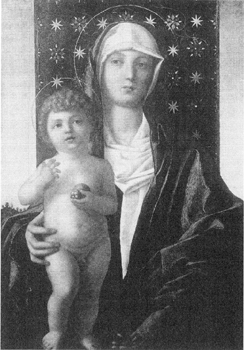

Still missing: Giovanni Bellini

, Madonna and Child,

from the Kaiser Friedrich Museum, Berlin

This is, therefore, a story without an end. It has been sixty years since the Nazi whirlwind took hold, sweeping the lives of millions before it. Never had works of art been so important to a political movement and never had they been moved about on such a vast scale, pawns in the cynical and desperate games of ideology, greed, and survival. Many were lost and many are still in hiding. The miracle of it all is the fact that infinitely more are safe, thanks almost entirely to the tiny number of “Monuments men” of all nations who against overwhelming odds preserved them for us.

NOTES

CURRENCY VALUES

, 1939

$1.00 = RM 2.50

$ 1.00 = FF 50

$1.00 = Dfl 1.90

$1.00 = SF 4.30

Dfl 100 = RM 133

FF 20 = RM 1

ABBREVIATIONS

| AAA | Archives of American Art, Washington, D.C. |

| ANF | Archives Nationales de France, Paris. |

| CIR | Consolidated Interrogation Report |

| DIR | Detailed Interrogation Report |

| FRUS | Foreign Relations of the United States |

| LC | Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, Washington, D.C. |

| MFAA | Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives |

| NA | National Archives, Washington, D.C. |

| NGA | National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. |

| OSS/ALIU | Office of Strategic Services/Art Looting Investigation Unit |

| RC | Roberts Commission |

| RG | Record Group |

| SD | State Department, Washington, D.C. |

| SG | Secretary General |

| UST7FFC | United States Treasury, Foreign Funds Control, Washington, D.C. |

1. PROLOGUE: THEY HAD FOUR YEARS

1.

M. Feilchenfeldt, interview with author, 1986.

2.

J. Pulitzer, Jr., letter to author, November 20, 1986.

3.

Ibid.

4.

Quoted in P. Gardner, “A Bit of Heidelberg Near Harvard Square,”

ArtNews

, Summer 1981.

5.

P. Assouline,

An Artful Life

(New York, 1990), p. 258.

6.

AAA, Barr Papers, Barr to Mabry, July 1, 1939.

7.

Beaux Arts

, “La Vente des oeuvres d’art dégénérés à Lucerne,” July 7, 1939. Translated by author.

8.

A. Hentzen,

Die Berliner National-Galerie im Bildersturm

(Berlin, 1971), p. 53.

9.

Barr Papers, various letters.

10.

Alfred H. Barr, “Art in the Third Reich—Preview 1933,”

Magazine of Art

, October 1945, p. 213.

11.

Ibid., p. 214.

12.

Barr Papers, undated note.

13.

Institute of Contemporary Art,

Dissent: The Issue of Modern Art in Boston

, exhibition catalogue (Boston, 1985), p. 32.

14.

H. Lehmann-Haupt,

Art under a Dictatorship

(New York, 1954), p. 15.

15.

Cited in B. Hinz,

Art in the Third Reich

(New York, 1979), p. 49.

16.

Ibid., pp. 49–50.

17.

Lehmann-Haupt, op. cit., pp. 37–40.

18.

Hentzen, op. cit., p. 61.

19.

A. Speer,

Inside the Third Reich

(New York, 1970), p. 93.

20.

B. M. Lane,

Architecture and Politics in Germany 1918–1945

(Cambridge, Mass., 1985), pp. 156–58.

21.

Hinz, op. cit., pp. 25–26.

22.

Speer, op. cit., p. 49.

23.

Ibid., p. 27.

24.

Hentzen, op. cit., pp. 10–16.

25.

Lehmann-Haupt, op. cit., p. 75.

26.

Baltimore Museum of Art,

Oskar Schlemmer

, exhibition catalogue (Baltimore, 1986), p. 204.

Other books

A Growing Passion by Emma Wildes

Rosemary and Rue by McGuire, Seanan

The Sorcerer's Vengeance: Book 4 of the Sorcerer's Path by Brock Deskins

Circus by Alistair MacLean

yolo by Sam Jones

The Hunt for Summer (NSC Industries) by Sidebottom, D H

Sweetgrass by Monroe, Mary Alice

When Sparks Fly by Autumn Dawn

Krampus: The Three Sisters (The Krampus Chronicles Book 1) by Halbach, Sonia

Sucker Punch by Pauline Baird Jones