The Rape of Europa (62 page)

Read The Rape of Europa Online

Authors: Lynn H. Nicholas

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Art, #General

Like hyenas the Anglo-American barbarians in the occupied western territories are falling upon German works of art and beginning a systematic looting campaign. Under flimsy pretexts all private houses and public buildings in the whole area are searched by art experts, most of them Jews, who “confiscate” all works of art whose owners cannot prove beyond doubt their property rights…. These works of art, stolen in true Jewish style, are transferred to Aachen, where they are sorted and packed and then dispatched to the U.S.A.

2

Meanwhile, at every step the Army bureaucracy, impatient with the irritating demands of the Monuments officers in the midst of battle, made the efficient use of the few specialists nearly impossible. Stout was refused clearance to go from one headquarters to another. SHAEF would not print Off Limits notices. Patton’s Third Army, headed directly for southern Germany and the greatest concentration of repositories, even suggested that MFAA officer Robert Posey’s presence was unnecessary, and that he be relieved. Stout and his colleagues did not give an inch, and by constant badgering of headquarters staffs and wide distribution of the above propaganda, managed to maintain their presence, which in a short time would be recognized at all levels as very necessary indeed.

They had known about Siegen since October. In December Mlle Valland’s revelations had added the ERR treasure castle of Neuschwanstein and four others to the list. From liberated Metz came news that the stained glass windows of the Strasbourg Cathedral and other Alsatian treasures were in a mine at Heilbronn. By the end of March, Walker Hancock had followed Stout to Cologne and on to Bonn and found Metternich’s assistant, who added 109 depositories to the list. Rushing from one headquarters to another, Hancock pinpointed them on the operations maps of the three Army Corps within Third Army.

3

Of the Berlin evacuations and the dramas in the Salzkammergut they as yet knew nothing. Stout felt that Siegen, which he knew contained Charlemagne’s relics, might be the most important repository of all, and the tactical

troops approaching the city were sent special cables with details of its possible contents. Well before the town had been taken, Stout had asked permission to go in, setting a tentative date of April 2.

On the same Easter Sunday which had so frustrated Goebbels, he and Walker Hancock set out for this objective, picking up the Vicar of Aachen Cathedral on the way. There was only one road, covered with rubble and bloodstains, which was not under fire. American patrols were still rounding up pockets of Germans, while from across the river Sieg the main German body fired sporadically. The warnings sent ahead had been heeded;

indeed, the mayor of Siegen had been amazed that one of the first questions the American commander who took the city asked was, “Where are the paintings?”

4

The Monuments men found the mine heavily guarded by members of the Eighth Infantry Division. With the Vicar they searched for the proper entrance. Up to now there had not been anything unusual about the shattered town; they had seen many in the last weeks. But once they entered the mine, Stout wrote,

what followed was not commonplace…. The tunnel… was about six feet wide and eight high, arched and rough. Once away from the entrance the passage was thick with vapor and our flashlights made only faint spots in the gloom. There were people inside. I thought that we must soon pass them and that they were a few stragglers sheltered there for safety. But we did not pass them…. We walked more than a quarter of a mile … other shafts branched from it…. Throughout we walked in a path not more than a foot and a half wide. The rest was compressed humanity. They stood, they sat on benches or on stones. They lay on cots or stretchers. This was the population of the city, all that could not get away. There was a stench in the humid air—babies cried fretfully. We were the first Americans they had seen. They had no doubt been told we were savages. The pale grimy faces caught in our flashlights were full of fear and hate … and ahead of us went the fearful word, halfway between sound and whisper, “Amerikaner.” That was the strange part of this occurrence, the impact of hate and fear in hundreds of hearts close about us and we were the targets of it all.

It took a child to relieve the tension. Stout felt something touch his hand; turning his light in that direction, he saw a small boy:

He smiled and took hold of my hand and walked along with me. I should not have let him do it, but I did and was glad. What could have made him know that I was not a monster?

5

This was not the shaft which contained the repository. The proper one was not much less crowded, but its occupants were Allied prisoners of war and forced laborers clamoring to know when they could go home. In a locked room measuring about two hundred by thirty feet, with vaulted bricked walls and concrete floors, were nearly six hundred high-quality paintings from the Rhineland museums, a hundred sculptures, and stacks of packed cases. Here were the manuscript of Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony and the great oaken doors of St. Maria in Kapitoll of Cologne. Mold covered many of the pictures. The ecstatic vicar found six cases containing

the gold and silver shrines with the relics of Charlemagne, the robe of the Virgin, and the rest of the cathedral treasure. The conditions were so bad that immediate evacuation was called for, but there was as yet no place to take the fragile objects. All Stout and Hancock could do for the moment was post guards and convince their commanders of the importance of this room. As they left, a demented old man followed them, screaming of Nazi atrocities. In the darkness they drove slowly back to their billets on roads jammed with muddy tank retrievers.

The hiding places were not all so hellish; a few days later Stout and Hancock would find another major part of the Rhineland collections in two serene and idyllic refuges utterly undisturbed deep in the country on the river Lahn.

6

Their colleagues were finding other things. The unlikely team of Robert Posey (a bluff architect definitely not part of the museum crowd) and Private Lincoln Kirstein (who had been instrumental in the

founding of the Museum of Modern Art) had quite by chance discovered the hiding place of the Ghent altarpiece.

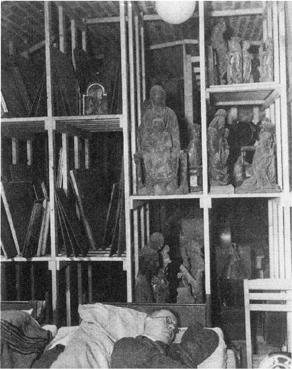

Art and Man sheltered at Siegen

Captain Posey had been stricken with a toothache while in Trier and consulted a German dentist, who revealed that his son-in-law had been involved in Kunstschutz activities in Paris. The dentist guided Posey and Kirstein to his daughter’s house, where they found Dr. Hermann Bunjes, once so helpful to Goering. The house was decorated with photographs of French monuments, undoubtedly from the documentation project undertaken by the German Institute in Paris. Bunjes, who in a very short time poured forth volumes of information—including the existence of Alt Aussee—did not fail to mention that he had once studied at Harvard and, now that the war was over, would like to work for the Americans. It also soon appeared that he would even more like to have a safe-conduct for himself and his family to Paris so that he could finish his research on the twelfth-century sculpture of the Ile de France. In the course of these outpourings he confided that he had been in the SS and now feared retribution from other Germans. Posey and Kirstein, who as yet knew little of the machinations of the ERR, found him rather charming, but could offer him nothing, and left. Charm had masked desperation: after a subsequent interrogation, Bunjes shot his wife, his child, and himself.

7

While their fellow officers were thus engaged, another team, consisting of Captain Walter Huchthausen and Sergeant Sheldon Keck, a conservator in civilian life, had set out in response to an inspection request from a forward unit of the American Ninth Army, somewhere north of Essen. Finding their chosen route impassable, they tried to detour around, and soon found themselves on an autobahn heading east. After a time Sergeant Keck noticed that there were suddenly no other American vehicles in sight, but Huchthausen, who felt sure that they were safe, pressed on. Finally they saw American soldiers peering over the highway embankment, but when they stopped to ask directions their jeep was raked with machine-gun fire. Keck dove into a foxhole, but Huchthausen was hit. From the foxhole Keck could not see him. Another GI reported that the captain “was bleeding from the ear, that his face was snow white.” While Keck was making his way to the nearest command post, Huchthausen’s body was taken away by medics. For thirty-six hours Keck searched one medical unit after another before he was told of Huchthausen’s death.

8

This second loss occurred just as Patton’s Third Army, racing across Germany, arrived in the Werra region of Thuringia and took the small town of Merkers. On April 6 an MP patrol stopped two women walking on the outskirts of town in violation of the curfew. After questioning them the MPs offered to drive the ladies on into Merkers. As they were passing the

entrance to the Kaiseroda mine, the women told the soldiers that it was “where the gold bullion was kept.” Their story was soon confirmed by other DPs and prisoners of war who had been forced to unload the gold when it arrived, and who indicated that the mine probably contained a large part of Germany’s gold reserves. This was not just a bunch of old pictures which could be protected by a couple of guards. After a few soldiers were caught with helmets full of gold coins, Patton sent an entire tank battalion and seven hundred men to guard every possible access to the mine, and ordered reports of the discovery to be censored.

Responsibility for securing this mine’s contents went not to the MFAA but to the Financial Section of SHAEF, whose deputy chief was Col. Bernard Bernstein, a trusted insider from Morgenthau’s Treasury Department, where heated discussions on the future of Germany were still in progress. In the absence of any firm Allied policy Bernstein acted on the basis of the latest draft “Financial Directive,” proposed on March 20, which called for the impounding of “all gold, silver, currencies, securities … valuable papers, and all other assets” of various categories including “works of art or cultural material of value or importance, regardless of the ownership thereof.”

9

To deal with the estimated four hundred tons of art from Berlin’s museums in the mine, Bernstein called in Robert Posey, who had so recently been considered superfluous by Third Army. Posey informed MFAA chief Geoffrey Webb of the find, and requested the services of technical expert Stout. By the time they arrived, the story of the gold had leaked to the world. Furious, Patton fired the responsible censor. Stout and Webb were surprised to find that Colonel Bernstein had taken custody of the entire contents of the mine and that, not being Third Army, they needed his permission to inspect the works of art. To back up his authority, Bernstein produced a letter from Patton himself. After some hours permission was granted to Stout, but not to the British Webb. Stout was told that he was to stay at the site until further notice, and was billeted with a large contingent of financial staff.

Before anything could be moved the mine was inspected by Generals Eisenhower, Bradley, and Patton, who later joked over dinner about what they could have done with the trove “if these were the old free-booting days when a soldier kept his loot.” A bit of levity was badly needed. The mine visit was bracketed by their first view of a different sort of repository, the Nazi death camp at Ohrdruf—where thirty-two hundred emaciated bodies, naked and covered with lice, had lain strewn about where their captors had shot them before they fled—and the news of Franklin Roosevelt’s death, which came in the night.

Other books

When Fangirls Lie by Marian Tee

Center Stage! (Center Stage! #1) by Caitlyn Duffy

Thomas Jefferson Dreams of Sally Hemings by Stephen O'Connor

Desire by Design by Paula Altenburg

Since You've Been Gone by Morgan Matson

Dangerously In Love by Allison Hobbs

Wicked Break by Jeff Shelby

The Drowning Girl by Caitlin R. Kiernan

The Murder on the Links by Agatha Christie

Haiku by Stephen Addiss