The Rape of Europa (29 page)

Read The Rape of Europa Online

Authors: Lynn H. Nicholas

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Art, #General

Once in Marseilles, Fry was to find his task almost overwhelming. As cover he started an American relief organization. Eager exiles soon taught him all the tricks of false papers and escape routes to Spain. Help came from such unexpected undercover operatives as André Gide, Henri Matisse, and the aged Aristide Maillol, who sent his model as a Pyrenees guide, after he himself had shown her how to cross the mountain ranges. But only Fry could help with the endless process of obtaining an American visa from the U.S. consulate, which often regarded the refugees as dangerous left-wing agitators. The lucky recipients had to be chosen, by an agonizing process of triage, from some eighty applicants a day. In one ten-day period in October he managed to get writer Lion Feuchtwanger, Werfel and Mahler, plus three of Thomas Mann’s relations off to New York. The journeys were not normal. Feuchtwanger (who had been rescued from a French internment camp by a sympathetic assistant American consul with the historic name of Miles Standish), Werfel, and Mahler, who was carrying the manuscripts of Werfel’s

Song of Bernadette

and Bruckner’s Third Symphony in her rucksack, climbed out over the Pyrenees. The resultant publicity, though it brought in much money in the form of contributions,

was not good. Himmler, who visited Madrid after the escape, extracted an agreement for stricter border controls from the Spanish government. The French and Portuguese followed suit, adding all sorts of exit and transit visas to the already daunting documentation necessary for freedom.

73

After this episode Fry felt it would be wise to be more private and rented a villa—dubbed “Château Espèrevisa”—just outside Marseilles which soon became an extraordinary artistic center. The presence of surrealist writer André Breton and his equally surrealistic wife, Jacqueline (“blonde, beautiful and savage with painted toenails, necklaces of tiger teeth, and bits of mirror glass in her hair”

74

), attracted the painter Max Ernst, who arrived after surviving a series of detention camps. A host of others lived in or spent their days at the villa, where they passed the time creating surrealist montages—Breton decorated the dinner table with an arrangement of live praying mantises—and holding exhibitions.

Word of this scene did not take long to reach Peggy Guggenheim, who, after many convolutions described at length in her memoirs, paid for the transatlantic passages of Ernst (whom she later married in New York), André Masson, Breton, and all their families, and helped the committee finance the escapes of Chagall, Lipchitz, and many more. There was a quid pro quo: for $2,000, minus the cost of the fare, Peggy asked for some of Ernst’s pictures. She did well, acquiring quite a generous number. Indeed, she had never stopped buying from needy artists who, like herself, were progressing toward escape.

75

Ernst left on May 1, 1941, having finally obtained his American visa. But his French exit papers were not in order, and at the border he was asked to open his bags. The paintings they contained were spread all over the customs area and Ernst was closely questioned about his artistic ideas. After a time the inspector informed him that his papers were not valid. He must return to Pau on the next train, which was standing on the near track. Under no circumstances, said the inspector, should he board the train on the far track, which was going to Madrid, adding, “Above all, monsieur, do not make a mistake. I adore talent.” Ernst made it to Madrid and went on to Lisbon. Feeling too encumbered by baggage, he went to the post office and sent one of his biggest paintings,

Europe after the Rain II

, to the Museum of Modern Art in New York by regular mail. It arrived.

76

Chagall, who was living in an ancient stone cottage in the village of Gordes, northwest of Marseilles, and who was very reluctant to leave, had a harder time. Fry had finally persuaded him to go, after having quieted his many worries, including the doubt that there would be cows in America, when he was arrested by Vichy police and only freed when Fry threatened to inform

The New York Times.

77

This ploy was successful, but the French clearly would not tolerate Fry forever. By August 1941 the United States consul and even Eleanor Roosevelt knew the operation was over. Fry tried to persuade Peggy Guggenheim to carry on for him, but the ever more frightening atmosphere of Marseilles and strong pressure from the consul were too much for her, and she declined. But it was not until she was questioned in her hotel by French police, whose chief apologetically released her upon discovery of her American papers, that she too got on a train heading for Spain.

Because of her name she was stripped and searched “for illegal currency” at the frontier, but she had none and continued on to Lisbon to meet Ernst and the rest of her family. On July 14, 1941, they all arrived in New York, where Ernst was immediately detained at Ellis Island as a German national. During his incarceration Peggy and his dealer visited him daily, crossing to the island in a small boat. After a barrage of recommendations from Alfred Barr and MoMA patrons John Hay Whitney and Nelson Rockefeller, Max Ernst too was allowed to set foot on American soil.

78

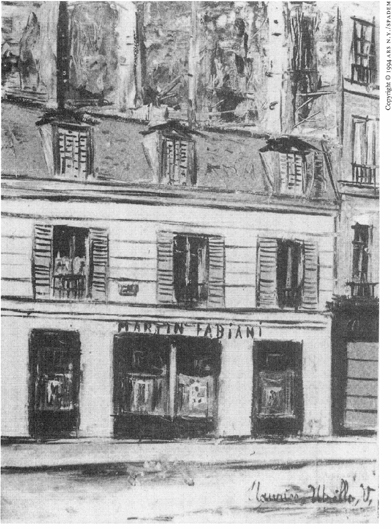

Martin Fabiani’s shop in 1943, by Utrillo (Photo by Henri Tabak)

VI

BUSINESS AND PLEASURE

France: The Art Market Flourishes;

Nazi Kultur Withers

The art market in France was, if anything, even more prosperous and fraught with intrigue than that in Holland. As the occupation government took hold, both sides had been impatient to revive the trade. The Archives Nationales files on the Kunstschutz are full of obsequious letters to Count Metternich from cash-starved countesses, Russian emigrés, and dealers of all kinds offering their possessions and wares. Everyone had apparently heard of the German propensity to spend.

Officials of the Hotel Drouot, the famous Parisian auction house, asked permission to resume sales on September 26, 1940. This was granted by Dr. Bunjes on condition that all catalogues be sent to him, that all works valued at more than FFr 100,000 be indicated, and that the name and address of the purchasers of such items be reported.

1

Like its Dutch and German counterparts, the Drouot was about to have its most successful years of the century. In the 1941–1942 season alone they would sell over a million objects; in March 1942 a Rotterdam paper reported on its front page that the Drouot was “filled with onlookers and buyers” and that the year 1941 had beaten all previous records, citing examples back to 1824. People bought everything they could get their hands on. “For want of Watteaus they bought presumptive Paters,” reported the Dutchman, two canvases by this artist having been snapped up for FFr 1.05 million.

2

Nineteen forty-two was even better, crowned by the phenomenal sale of the late dentist Georges Viau’s Impressionist collection on December 11—14. The auctioneer, Etienne Ader, had written to the Kunstschutz not to list works that would sell for FFr 100,000, which had become rather routine, but rather to report those expected to pass the million mark. Ader’s estimate that only one, a

Vallée de l’Arc et Mont Ste.-Victoire

by Cézanne, would reach this figure was wildly off.

3

The 120 works together brought FFr 46.796 million, the highest total ever reached at the Drouot at

a single session, to which had to be added a 10 percent luxury tax on top of a 15 percent sales tax. The Cézanne brought FFr 5 million, for which, a German report noted, one could easily have bought a château with considerable acreage. Degas’s

Femme s’essuyant après le bain

went for FFr 2.2 million, and thirteen other lots were sold for well over a million francs apiece.

The event got heavy press coverage both in Paris and Germany. Paul Colin of

Le Nouveau Journal

described the six hundred seated attendees, who were soon mobbed by a huge standing-room-only crowd, as paradoxically very

“vieille

France,” noting that it was filled with “monocles, and white moustaches à la gauloise,” elegant ladies of a “very certain age,” and jackets adorned with the red rosettes of the Légion d’honneur. He mentioned that no Jews were allowed to attend, and nastily pointed out that “the Parisian market needs neither Hebrews nor Yankees to have sensational prices reached … which,” he continued, “were absurd and accidental” and due to “Degas snobbism added to Viau snobbism.” As for the Cézanne, “we will perhaps never again find two buyers crazy enough—the word is not too strong—to bid each other up to 5 million for a little landscape (55 × 46 cm).” The Louvre was derided for refusing the Degas in 1918, when it could have been had for FFr 20,000.

4

German reports on the event were a bit more subtle, but no less nasty, attributing the high prices to “the needs of the nouveaux riches for capital investments.” One had the impression, one writer remarked, “that the buyers were more concerned with getting rid of their newly acquired paper money as quickly as possible.” He evidently did not know that the major buyer at the sale was not a French black marketeer but the German dealer Hildebrand Gurlitt, one of the buyers for Linz, who in addition to the Cézanne bought three other million-plus pictures: a Corot

Paysage composé, Effet gris;

a proscribed Pissarro; and for FFr 1.32 million a small Daumier

Portrait of a Friend.

The truth of the matter was that in France these “degenerate” works were among the hottest items in an overheated market and were being traded and bought to a large degree by those who had condemned them.

Alas for Gurlitt, both the Cézanne and the Daumier were fakes. The good dentist, it seems, loved to “finish” oil sketches by well-known artists, and copy other works outright. The little Daumier was a copy of the real picture, which had also belonged to Viau, but been sold elsewhere; the Cézanne pure invention. It is now in the study collection of the Musée d’Orsay.

5

Individual dealers, decorators, and purveyors of every stripe were doing just as well as the Drouot. The Germans were no different from the visitors

who had lost themselves in the antique-buyer’s paradise of Paris for generations. Behind the dignified façades of many an apartment building a colorful array of amateurs and professionals carried on an enormous secret market in their efforts to sell their conquerors everything short of the Eiffel Tower. One lady repeatedly offered Goering an entire Spanish courtyard. Another gentleman wondered if he would be interested in buying “twelve historic stone capitals which come from the Palace of the Tuileries and bear the ‘N’ of Napoleon,” and which were now “at my house … where I had intended to build a temple.” Monumental offers of this nature were not frivolous: inventories of the Reichsmarschall’s collections reveal that he actually did buy “a small eighteenth-century circular temple with six columns” and “the Cloister of the Cistercian Abbey of Berdoues (Gers)” from dealer Paul Gouvert.

The Galerie Charpentier, at the behest of Kajetan Mühlmann’s half-brother Josef, put on a show of medieval and Renaissance objects which was visited by Goering, who bought the lot. From his own very decorated apartment, the Vicomte de la Forest-Divonne sold carefully arranged objects and paintings (often obtained from ERR leftovers or the Clignancourt flea market) as if they were his own, claiming always that they had been in the family for generations. To encourage sales, clients were served champagne as they pondered. Another noble lady, the Countess de la Béraudière, worked the black market, accepting only cash transactions.

6

The art trade swarmed with middlemen fronting for French citizens who preferred not to reveal to whom they had sold. Thousands of works of art changed hands without receipts or any kind of record.

The architects helping Hans Frank refurbish the castle at Cracow came and shipped carloads full to the East. The Rhineland Museums (Krefeld, Essen, Bonn, Wuppertal, and Düsseldorf) had a whole team of curators covering Paris who spent well over FFr 40 million on French paintings and decorative arts, which even included a good number of Impressionists. Albert Speer bought twenty-five cases worth of

objets

, and the sculptor Arno Breker bought works by French artists he admired and shipped them home along with twenty tons of plaster, wine, and cologne. Dr. Hans Herbst spent FFr 15 million on items which were dispatched to the auction rooms of the Dorotheum in Vienna for resale, while Josef Mühlmann travelled the countryside to supply clients in Berlin and Poland, and a certain Herr Possbacher filled orders to the tune of FFr 4.5 million for lesser Nazi party officials unable to visit the City of Light.

7

Other books

Bound to Be a Groom by Megan Mulry

Chump Change by Dan Fante

As Gouda as Dead by Avery Aames

Conquest by Victoria Embers

The Nanny Arrangement by Lily George

Counselor of the Damned by Angela Daniels

Love Only Once by Johanna Lindsey

Arrive by Nina Lane

Cajun Magic 02 - Voodoo for Two by Elle James