The Rape of Europa (11 page)

Read The Rape of Europa Online

Authors: Lynn H. Nicholas

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Art, #General

Anyone who could, from Kenneth Clark and Bernard Berenson to Matisse and Picasso, travelled the long road to see it.

55

Late in August one of the last visitors, the Paris dealer René Gimpel, wrote in his diary:

The conflagration is not far from bursting upon us. We have been here for forty-eight hours to see the Prado Exhibition…. Death hangs over our heads, and if it must take us, this last vision of Velázquez, Greco, Goya, Roger van der Weyden, will have made a fine curtain.

56

A year later, Gimpel, a Resistance fighter, would die in a concentration camp.

The pace of preparation in the great museums intensified during the summer of 1939 and Europe’s inexorable progress toward war. Everyone

feared that closing the museums would be a terrible blow to public morale, but the breaking point was reached with the announcement, on August 22, that a German-Soviet nonaggression pact was about to be signed. The National Gallery in London closed on the twenty-third. King George had stopped by to watch the packing at the Tate, which cleared its galleries one by one at midday on the twenty-fourth. Along with the trains taking millions of Londoners to safety went the Royal train, filled with the packed treasures of the capital, creeping along at ten miles an hour to keep vibration to a minimum. The Dutch museums got word of their colleagues’ actions and immediately followed suit. The museums of Paris were authorized to close their doors on the afternoon of Friday, August 25. Like an enormous kaleidoscope, the treasures of Europe would soon be flung outward into a strange new pattern.

Rembrandt’s

Night Watch

rolled for storage

The careful preparations were now more than justified. Most of the British objects reached their designated refuges even before the formal declaration of war on September 3. By the fifth virtually everything of importance had been moved. In Holland, after dutifully putting some things in the storage areas of the museum, the director of the Rijksmuseum sent the

Night Watch

and his other most important pictures to a castle in

Medemblik, north of Amsterdam. The Mauritshuis availed itself of the vaults of a local bank, and in one of the most unusual solutions to the problems of protection, the Stedelijk Museum stored its collections on barges grouped on a canal near Alkmaar. On September 13, nearly two weeks after the outbreak of war, the Ministry of Education appropriated DFl 2 million for the building of shelters. The Belgians, more relaxed, also put their collections in their basements and vaults, but decided they might as well leave the Memling show in Bruges open, as it only had a few weeks to run.

57

At the same time the carefully designed French plan was initiated. Orders to take down the stained glass windows were issued on August 27; within ten days more than eighteen thousand square meters of windows from the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris and the cathedrals of Bourges, Amiens, Metz, and Chartres were secured. At the museums, curators and technicians who had left for the sacred August vacation were recalled by telegram. Within hours the great gallery of the Louvre looked like a gigantic lumberyard. In the midst of boxes and excelsior, secretaries typed lists in quadruplicate of the contents of each case, marked only with numbers to disguise their contents, while the official assigned to each section coordinated the order of packing. One curator was amazed to find her packers, recruited from two department stores, the Bazar de l’Hôtel and the Samaritaine, dressed in long mauve tights, striped caps, and flowing tunics, as if they had just stepped out of the fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Italian pictures they were about to wrap.

58

As the ultimatums flew back and forth the pace increased. Many of the exhausted, dust-covered workers slept their few hours during the nights of September 1 and 2 in the Louvre itself.

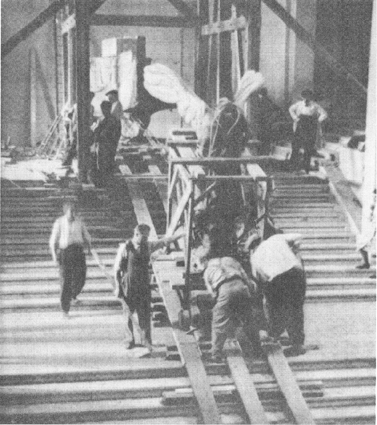

On the afternoon of September 3 news of the formal declaration of war was announced to many of the Louvre staff as they stood in a group at the top of the staircase, around the great

Winged Victory of Samothrace.

They were informed that all the most important works must be out by that night. The

Victory

now had to descend the long staircase and be taken to safety:

Monsieur Michon, then curator of the department of Greek and Roman antiquities … gave the order for the removal. The statue rocked onto an inclined wooden ramp, held back by two groups of men, who controlled her descent with ropes stretched to either side, like the Volga boatmen. We were all terrified, and the silence was total as the Victory rolled slowly forward, her stone wings trembling slightly. Monsieur Michon sank down on the stone steps murmuring, “I will not see her return.”

59

Paris:

Winged Victory

descending a staircase (Photo by Noel de Boyer)

Scenery trucks from the Comédie-Française had been brought in to move the biggest paintings. Although some had been rolled, Géricault’s enormous

Raft of the Medusa

was too fragile for this treatment. The trucks moved off at six in the evening, just as darkness was falling. In the careful planning, which had included measuring all the bridges between Paris and Chambord, the trolley lines in the town of Versailles had somehow been overlooked, and the

Raft

became hopelessly ensnared in crackling wires. Magdeleine Hours, sent off in the total darkness to wake her colleagues at the Palace of Versailles, vividly describes in her memoirs the terrifying

task of finding the doorbell, somewhere on the vast entrance gate. In the end, the

Raft

and some of its companions were left in the Orangerie until chief curator René Huyghe could rescue them some weeks later, this time accompanied by a team of post office employees who carried long insulated poles to raise any threatening wires.

Through the night the precious convoys crept toward Chambord. It was not easy to keep them together. Most of the drivers had never driven outside Paris or at night, and the blackout forbade the use of headlights. The roads were also jammed with the populace of the city, seeking refuge beyond the traditional protection of the Loire. Military cars and travelling circuses were mixed with the rest. One curator looked at a passing van and recognized the insignia of the Banque de France on its door; pictures were not the only treasures leaving Paris. Just outside Chambord, the progress was further slowed by thick fog. A vehicle check revealed the absence of the truck containing all the Watteaus. The driver had followed a bicycle light in the fog, and come to a terrified halt only a few feet from the river-bank. Dawn was breaking as the convoy arrived at the great peaceful chateau.

60

The exodus continued everywhere well into October, as lesser collections followed the masterpieces. By the first of November almost everything was where it was supposed to be, firefighting equipment was in place, sand spread on floors, hygrometers working, and guards and their families settling into their new country lives. Having little now to do, John Rothenstein, director of the Tate, whose job was still considered too important to allow him to join the Army, went off to the United States to promote the British cause. Kenneth Clark volunteered for work at the brand-new Ministry of Information. In France most of the male curators were drafted. Everyone was glad that the collections were safe. They could not know that the frantic days of packing and evacuation had only been a dress rehearsal.

III

EASTERN ORIENTATIONS

Poland, 1939–1945

Blitzkrieg it will be forever called: a revelation to the world, a sudden, devastating, preemptive campaign coming from nowhere. A strike which was over before anyone knew it, before Poland’s supposed allies could bestir themselves. A perfect military operation, using surprising new techniques against the heroic but antiquated Polish forces. Film footage preserves for us the drama of lines of tanks rolling past dead horses, infantry with ancient rifles running from dive bombers, the elegant Prussian war machine at work, arrogant in its reclamation of areas taken from its control by the hated Treaty of Versailles.

Never had lightning been more carefully directed. The location and execution of the Polish campaign should not really have surprised anyone. In 1926 the obscure Hitler had written a whole chapter on “Eastern Orientation” in

Mein Kampf

, advocating expansion beyond the “momentary frontiers” of 1914 “to secure for the German people the land and soil to which they are entitled on this earth … if we speak of soil in Europe today, we can primarily have in mind only Russia and her vassal border states.” He even foresaw “the general motorization of the world, which in the next war will manifest itself overwhelmingly.”

1

All this was not taken seriously at the time, but by 1939 these ideas had become his firm policy.

For many months detailed plans had been ready at the German General Staff for this invasion, spelled out even down to the date in the famous “Case White” directive of April 3, 1939. For many more months, Hitler had kept relentless economic and diplomatic pressure on Poland by demands for access to Danzig, propaganda barrages at home, the expulsion of Polish Jews from the Reich, and unequal trade proposals, creating, as he readily admitted, “propagandist reasons” for the long planned attack.

2

Hoping beyond hope, the Polish government waited well into the summer of 1939 to warn its citizens to prepare for war. A United States embassy cable reported the first precautionary measures on June 26. Landowners in the western provinces were advised to send their livestock

“to the interior,” and to speed up the harvesting of cereal crops. “Secret advice” was sent “to all persons living in the aforementioned zone and possessing valuable works of art or other transportable factors of value, to move them gradually to the interior. Particular emphasis is laid on the necessity of conducting these movements in such a way as to cause the minimum attention and alarm amongst the local community.” To the rest of the populace they only announced that each house in Warsaw should provide itself with a bomb- and gas-proof shelter by August 1.

3

Perhaps with a sigh of resignation many of the Polish gentry once again sent their collections eastward to what they hoped was safety. The “continual need to rescue the evidence of ancient history and culture from the destructive power of the Partitioning Powers” (Austria, Prussia, and Russia) had kept Polish collections in a state of flux for nearly two centuries. Objects had repeatedly been carried off to Berlin or Russia, or been evacuated by their owners to Paris and Switzerland. The famous Czartoryski collections, consisting of more than 5,000 paintings, antiquities, porcelains, and graphics, were removed from the family-built museums in Goluchow (outside Poznan) and Cracow, and taken to the vaults of a country house at Sienawa. Into the darkness went Leonardo’s

Lady with the Ermine

, Rembrandt’s

Landscape with the Good Samaritan

, and Raphael’s

Portrait of a Gentleman.

From many other country houses, such collections found refuge with friends and relations in the East or were sent to Warsaw’s National Museum. The Tarnowskis, to be extra safe, sent twenty of their best pictures to the museum founded by the Lubomirskis in Lvov, where that family’s magnificent collection of Dürer drawings was also kept. Others could not be bothered: Prince Drucki-Lubecki buried his silver in the basement, and Count Alfred Potocki at Lancut packed away the best things in the usual hiding places and left the rest where they were.

4

Other books

Stepbrother With Benefits 10 (Second Season) by Mia Clark

Apache Death by George G. Gilman

Gold Dragon Codex by R.D. Henham

Lifers by Jane Harvey-Berrick

September (1990) by Pilcher, Rosamunde

#Rev (GearShark #2) by Cambria Hebert

Sweet Silver Blues by Glen Cook

A Week in Paris by Hore, Rachel

Voices from the Air by Tony Hill

Thorns of Decision (Dusk Gate Chronicles) by Puttroff, Breeana