The Race to Save the Lord God Bird (16 page)

Read The Race to Save the Lord God Bird Online

Authors: Phillip Hoose

MARCH 16

The old peasant squinted at the picture of the bird Giraldo Alayón had handed him, and then smiled. His smile split into a grin when Alayón clicked on his tape recorder and the rapid succession of toots and yaps came pouring out. These were sounds he

clearly recognized. Without hesitation he led Alayón directly to a tree whose upper limbs were stripped of bark.

clearly recognized. Without hesitation he led Alayón directly to a tree whose upper limbs were stripped of bark.

Alayón looked around. Here was a wild and primitive forest, with pine-carpeted mountains plunging steeply down to meet clear green streams lined with thick brush. Locals called the place Ojito de Agua. Ever since Lester Short had left, Alayón had been interviewing mountain people, looking for the best place to begin a new expedition when breeding season began. Ojito de Agua looked like the spot.

Alayón organized an all-Cuban Ivory-bill search team, the first ever. With him were herpetologist Alberto Estrada, two other scientists, a mule driver, four guidesâall hunters and miners who knew the mountains like the backs of their weathered handsâand a young photographer named Carlos Peña who had become famous in Cuba as a champion boxer. Their cook was an old woman who kept them strong with rice, beans, and canned meat.

LEARNING ABOUT BIRDS IN CUBA

At this writing, Cuba has about forty professional ornithologists and a much larger number of ornithology students. Classes in the island's natural history begin for all students in fourth grade. Cubans have learned about their birds with very little equipment. The island has little money, and scientists are often restricted by their government from traveling to conferences outside of Cuba.

So Cuban scientists work without batteries, pens, binoculars, paper, thermometers, or gasolineâusually for free. They do it for the love of learning. At Zapata Swampâa vast ocean of grass like the EvergladesâOrestes Martinez, known as “El Chino,” has become the world expert on three birds found only thereâthe Zapata Wren, the Zapata Sparrow, and the Zapata Rail. He started a bird club called “The Three Endemics” to help local children learn about these special birds. “Their fathers and uncles hunted them,” he says. “The children want to protect them. That means the birds have hope.”

They set out in February 1986, rumbling in a truck to a flat clearing in the lower mountains where they unloaded a huge canvas tent and set up a base camp. Then they divvied up the rest of the gear and food into their

mochilas,

or backpacks. They were fit, well prepared, and optimistic.

mochilas,

or backpacks. They were fit, well prepared, and optimistic.

The trail to Ojito de Agua seemed to have been made for goats. One part, which they marked as “Three-Rest Mountain,” was too steep and rocky for even the agile guides to accomplish in a single climb. For several days the team collected insects and reptiles and searched for Ivory-bills. On the morning of March 13, Estrada caught a brief glimpse of a huge black bird flashing across the path. It might have been a crow, but it struck Estrada as far too big, and he thought he saw white on the wing. Minutes later, several explorers thought they heard an Ivory-bill call far to the south. For the next two days they explored the hills in a state of keen expectation, but found no sign of the great woodpecker. Then, just after breakfast on the morning of March 16, they set out on an old lumber trail that zigzagged along a mountainside. Footing was difficult,

and the men frequently stumbled. By nine o'clock a light fog had reduced visibility and made the rhythmic crunching of their boots seem even louder. Soon a thin mist glistened on the green crowns of the huge old pine trees.

and the men frequently stumbled. By nine o'clock a light fog had reduced visibility and made the rhythmic crunching of their boots seem even louder. Soon a thin mist glistened on the green crowns of the huge old pine trees.

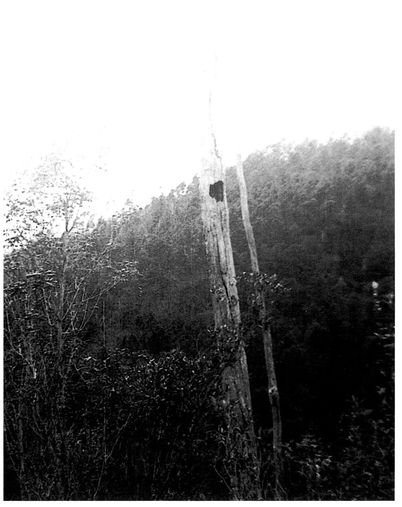

Giraldo Alayón surveys habitat during one of the expeditions when the Ivory-bill was rediscovered in Cuba in the mid-1980s

Alayón was alone in the middle of the pack, trudging with his head down, when he heard a crow call. He lifted his head to the right and, as he remembers, “I saw two big crows chase a female Ivory-bill. They were moving fast, from one side of the valley to the other. It was like a flash. Two big black birds, with another big bird ahead of them. But the one in front had a flash of white on the wings. I was frozenâcompletely paralyzed. And then it was over so fast. I screamed for the others to come back,

but it was gone by the time they got there. I stomped my foot and punched my fist in the air and screamed

âLo vÃ! Si! Si!'

[âI saw it!'] It was one of the biggest moments of my life.”

but it was gone by the time they got there. I stomped my foot and punched my fist in the air and screamed

âLo vÃ! Si! Si!'

[âI saw it!'] It was one of the biggest moments of my life.”

A week later he returned to Havana and immediately called Lester Short in New York. “I saw the Ivory-bill!” he said. “Come back!” Short was there in a matter of days, this time with his wife, ornithologist Jennifer Horne, as well as sound technician George Reynard. A well-equipped international team explored the forest for ten days straight, with spectacular success. One male Ivory-bill and at least one female were seen seven different times by six different people. The birds streaked across valleys and through trees like black-and-white comets, electrifying anyone who caught a glimpse.

Word of the rediscovery crackled around the island. On their way down the mountain, the searchers were met by a Cuban television crew coming up by mule to interview them. By the time they got back to Havana, even their hotel maids knew. Meetings were arranged with important officials who took notes as Alayón and Short made recommendations much like those of Tanner earlier: no cutting of trees within three and a half miles of the Ivory-bill site; no one allowed in the area except for scientists and wildlife managers; girdling of trees to provide more food. This time Cuban authorities took their advice and closed the area within a week.

Back in the United States, Lester Short told his story to reporters from

People

magazine and

The New York Times,

among many other publications. Privately, he worried about the birds. Though it had been breeding season, they hadn't seemed attached to any one place. Rather than calling to defend nesting territory, they had flown randomly around, acting like the last frantic survivors of a doomed population. “They seemed very wary,” Short recalled later. “They were like a hunted animal; they'd just disappear like the mist in front of you. You couldn't even chase them. They should have been on eggs by March, going to a regular site, but there was none of that. I thought maybe we were seeing first-year birds, maybe brother and sister ⦠I felt deep in my heart there might not be many more than these two or three.”

People

magazine and

The New York Times,

among many other publications. Privately, he worried about the birds. Though it had been breeding season, they hadn't seemed attached to any one place. Rather than calling to defend nesting territory, they had flown randomly around, acting like the last frantic survivors of a doomed population. “They seemed very wary,” Short recalled later. “They were like a hunted animal; they'd just disappear like the mist in front of you. You couldn't even chase them. They should have been on eggs by March, going to a regular site, but there was none of that. I thought maybe we were seeing first-year birds, maybe brother and sister ⦠I felt deep in my heart there might not be many more than these two or three.”

A year later, in 1987, Giraldo Alayón got one more look at an Ivory-bill. He was again at Ojito de Agua with an all-Cuban crew including his new bride, Aime Posada, also a biologist from Alayón's hometown of San Antonio. The Ivory-bill expedition

was their honeymoon. Their wedding reception had turned into a sort of planning session for the expedition until Aimé had shouted at the biologists, “Hey, this is my wedding day! Stop talking about birds!”

was their honeymoon. Their wedding reception had turned into a sort of planning session for the expedition until Aimé had shouted at the biologists, “Hey, this is my wedding day! Stop talking about birds!”

On March 16, the anniversary of the day he had seen the Ivory-bill the preceding year, Alayón awoke with a premonition that he would see it again. He turned to Aimé and whispered, “Today's the day.” She didn't stir. He pulled on his boots and went outside to fix

café con leche

for the crew. As the thick brew bubbled, he found himself thinking that maybe he should be paying more attention to crows. Maybe they competed with Ivory-bills for the grubs beneath the bark of the trees. If that was so, crows could be a key to finding the woodpeckers. Shortly after noon, he thought he heard an Ivory-bill call, a single sharp note sounding in the far distance. He couldn't be sure. The crew worked into the blazing heat of the afternoon, then broke for a lunch of sardines, crackers, and juice. Late in the afternoon they relaxed in the camp with a favorite activity: listening to taxidermist Eduardo Solana tell them ghost stories.

café con leche

for the crew. As the thick brew bubbled, he found himself thinking that maybe he should be paying more attention to crows. Maybe they competed with Ivory-bills for the grubs beneath the bark of the trees. If that was so, crows could be a key to finding the woodpeckers. Shortly after noon, he thought he heard an Ivory-bill call, a single sharp note sounding in the far distance. He couldn't be sure. The crew worked into the blazing heat of the afternoon, then broke for a lunch of sardines, crackers, and juice. Late in the afternoon they relaxed in the camp with a favorite activity: listening to taxidermist Eduardo Solana tell them ghost stories.

At about four-thirty, Giraldo and Aimé hiked back to the spot where Giraldo had first seen the Ivory-bill the year before. It was a good place to find crows. The couple picked their way along the narrow ridge overlooking the Yarey River until Giraldo halted. He turned around to face Aimé and, pointing toward the river, said, “This is the place where I saw the female Ivory-bill the first time.” At that very moment three black birds appeared, flying from right to left: a female Ivory-bill being chased by two crows. It was an exact reenactment of what happened on the very same day the year before. The three birds flapped high over the valley, winging back in the direction of the camp until they disappeared. Once again Giraldo was too stunned to reach for the camera that was dangling around his neck. But Aimé was gleeful. “The white patches just shone in the sun,” she remembers. “It was so big and pretty.” Aimé raced off down the trail to tell the others while Giraldo remained behind in case the Ivory-bill reappeared.

By the time the rest of the team had assembled at the spot it was almost dark. Eduardo Solana said he had seen the Ivory-bill, too, when it flew over the campsite. Chatting excitedly, the team made plans about what they were going to do when they saw it the next day, as they were sure they would. But they didn't see it the next day or

the day after that. Though they searched with all their knowledge, strength, and imagination, they never saw it again. And though explorers have tried to find the bird nearly every year since, the sightings of Giraldo, Aimé, and Solana are probably the last anyone in Cuba has seen of the

Carpintero real.

Aimé Posada remains the only Cuban woman ever known to have seen it.

the day after that. Though they searched with all their knowledge, strength, and imagination, they never saw it again. And though explorers have tried to find the bird nearly every year since, the sightings of Giraldo, Aimé, and Solana are probably the last anyone in Cuba has seen of the

Carpintero real.

Aimé Posada remains the only Cuban woman ever known to have seen it.

“All the four times I have seen it, I have seen it on March r6,” muses Giraldo Alayón in his study. “I think that day has some magic.” Alayón himself has led over a dozen expeditions since he last saw the Ivory-bill, all without success. As forests have collapsed throughout the world, finding the Ivory-bill in Cuba has become one of the great quests left in ornithology, like searching for the Fountain of Youth or El Dorado. When Alayón is asked, in his small, tidy home filled with bookshelves lined with vials of spider specimens, whether he thinks the Ivory-bill is extinct, he taps on his desk and then answers with the hopeful tone that some U.S. scientists adopt when asked the same question. “Is the bird extinct? ⦠Well, no one knows, of course, but if I had to bet, I would say no. No, this bird is still out there somewhere. It is an astonishing bird. It is a soul that links the love of nature and the love of the great forest that was its home. It is still alive. And we will find it.”

A deserted Ivorybill roost tree found in eastern Cuba

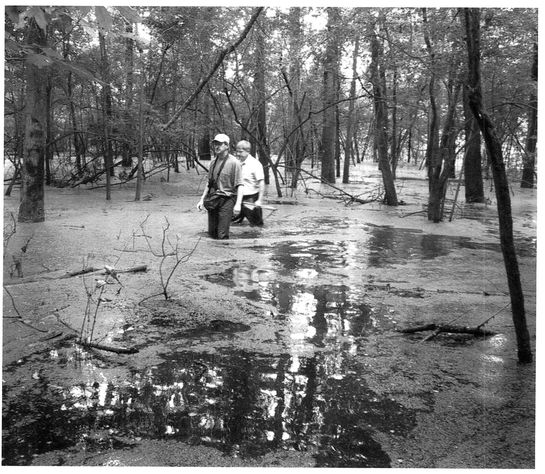

David Luneau (front) and biologist Richard Hines continue the search for the Ivory-bill in 2003

RETURN OF THE GHOST BIRD?

Without [hope], all we can do is eat and drink the last of our resources as we watch our planet slowly die. Instead, let us have faith in ourselves, in our intellect, in our staunch spirit.

âAnthropotogist Jane Goodall, who has lived among chimpanzees for more than forty years in Tanzania, Africa

A

NY STUDENT WHO PASSED THROUGH THE OFFICE DOOR OF PROFESSOR JAMES TANNER at the University of Tennessee was brought up short by a sign on his desk. Hand-carved into a block of wood, the message was positioned face out so that a visitor couldn't avoid it. The sign said “STUDY NATURE, NOT BOOKS.”

NY STUDENT WHO PASSED THROUGH THE OFFICE DOOR OF PROFESSOR JAMES TANNER at the University of Tennessee was brought up short by a sign on his desk. Hand-carved into a block of wood, the message was positioned face out so that a visitor couldn't avoid it. The sign said “STUDY NATURE, NOT BOOKS.”

Tanner didn't mean to show disrespect for books. Throughout his long life he had learned a great deal from reading. He was simply trying to pass on a personal truth, one that he had discovered in the low ridges of New York State as a boy. It was a truth that had guided him as a young man as he worked in the last swamp forests of the South, and one that still seemed as good as gold as he helped graduate students with their research in the forests of the Great Smoky Mountains: books helped, but if you wanted to understand nature, you learned your

real

lessons outdoors, watching and listening, noticing and puzzling, and inhaling the fragrance of living things.

real

lessons outdoors, watching and listening, noticing and puzzling, and inhaling the fragrance of living things.

Jim Tanner became a distinguished professor, founding the Graduate Program in Ecology at the University of Tennessee. And even as a white-haired old man he was

still able to outwalk his graduate students, leaving them gasping and bent over as he strode through the hills.

still able to outwalk his graduate students, leaving them gasping and bent over as he strode through the hills.

Still, like a professional athlete, he was always best known for work that he did in the early years of his life. As he sometimes told people, “I am the world expert on an extinct bird.” Being the world expert on the Ivory-billed Woodpecker was a little like being a world expert on UFOs or the Loch Ness monster. The job made Tanner the lifetime custodian of rumors, of Hashes, of questionable sightings.

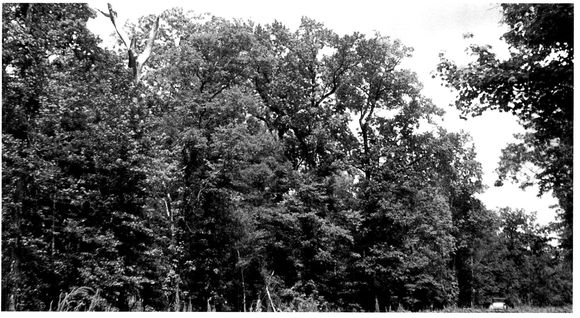

The Singer Tract in 1937, in all its glory. Note Tanner's car on the far right

In his office, he kept a list of the most believable Ivory-bill sightings. In 1949 there was a report that a pair had survived in the cutover rubble of the Singer Tract. But no one could prove it. The next year a pair was reportedly seen near the Apalachicola River in Florida. There was no evidence. In 1952 there was a report of a sighting twenty miles south of Tallahassee, and in 1954 several more reports from Florida, and on and onâa new report every few years. Tanner put the past behind him and pursued fresh interests, but always the Ivory-bill beckoned. Sometimes he went to track down a rumor himself. just as in the old days, but there was never a clear photograph, never a tape recording, never a moving picture. Tanner thought most of the observers

had really seen Pileated Woodpeckers. He thought the habitat the Ivory-bill needed was gone, that the great bird had truly disappeared from the United States. He tried to gain permission to search for the bird in Cuba, but he couldn't get a visa during the Cold War years.

had really seen Pileated Woodpeckers. He thought the habitat the Ivory-bill needed was gone, that the great bird had truly disappeared from the United States. He tried to gain permission to search for the bird in Cuba, but he couldn't get a visa during the Cold War years.

Tanner returned to the Singer Tract one last time in 1986, after an absence of forty-five years. Now it was called the Tensas River National Wildlife Refuge, and Tanner was invited back to tell the refuge managers about the forest that had been there before. One morning they all took a walk around Little Bear Lake, in the heart of what used to be Ivory-bill country. Passing by the massive stumps of cypress trees cut long ago, Tanner remembered that those very trees had once reminded him of “columns of a Greek temple.” His youthful companions noticed that he seemed “pensive,” and that he didn't say much. When they asked him how things had changed, he glanced around and said, “There is more sky, smaller trees, more trunks, and more saplings.”

There were other changes, of course. The Ivory-bills were missing, as were panthers, wolves, and other creatures Jim Tanner had once known. Even though the Tensas refuge was supposed to cover fifty thousand acres, in fact it covered much less. Bulldozers were still crushing trees to clear land for soybean fields on the very day Tanner arrived.

The same spot, forty-five years later, had become a soybean field

Fifth-grade students take notes on the environment at the Tensas River National Wildlife Refuge in the heart of the old Singer Tract

Tanner stayed in the area for about a week. Just before he left, he admitted that he had been depressed at first when he compared what he saw to his memory of the Singer Tract. But that couldn't keep a sense of optimism from welling up in him. “I'm tickled about the refuge,” he told his dinner companions. “It is not as big as I'd like, but it's off to a good start.” He hoped the trees remaining along the snaking Tensas River could be left alone to grow in peace. “Every kind of timber type grew in the Singer Tract,” he said. “These trees do grow fast, and if you come back in forty years you will be amazed.”

“SOMETHING I HAD NEVER SEEN BEFORE”

James Tanner died of a brain tumor in 1991, at the age of seventy-six. After his death, the Ivory-bill rumors and reports that he had fielded for so long went to Louisiana State University, the nearest university to the Singer Tract and the home of LSU's Museum of Natural Science. Since 1979, the museum's curator of ornithology has been Dr. James Van Remsen (known by everyone as “Van”). Most years, Van has gotten about ten reports of Ivory-bills. He has answered them politely, encouraging the caller to send him a photo or a video. Like Tanner, Van has assumed that most of the callers have really seen Pleated Woodpeckers.

Then came April I, 1999. Early that morning a twenty-year-old LSU forestry student

named David Kulivan climbed into his camouflage clothing, grabbed his shotgun, and drove off to hunt turkey. He chose the Pearl River Wildlife Management Area, a huge, tea-colored swamp forest about an hour from New Orleans. Early that morning, he was sitting quietly against a tree and cradling his shotgun when, he said, two Ivory-billed Woodpeckers landed on a tree nearby. One was a male, the other a female. He said he watched them closely for more than ten minutes and saw all the markings that distinguish an Ivory-bill from a Pileatedâthe white on the lower wings, the big white bills, the curve of the crests. At one point the birds were no more than thirty feet from where he was sitting. He had a camera, but it was zipped inside his jacket. He decided it would be better to remain still and keep his eye on the birds than to risk scaring them off by removing the camera and snapping the shutter. He later told a reporter, “I knew as soon as I saw them it was something I had never seen before.”

named David Kulivan climbed into his camouflage clothing, grabbed his shotgun, and drove off to hunt turkey. He chose the Pearl River Wildlife Management Area, a huge, tea-colored swamp forest about an hour from New Orleans. Early that morning, he was sitting quietly against a tree and cradling his shotgun when, he said, two Ivory-billed Woodpeckers landed on a tree nearby. One was a male, the other a female. He said he watched them closely for more than ten minutes and saw all the markings that distinguish an Ivory-bill from a Pileatedâthe white on the lower wings, the big white bills, the curve of the crests. At one point the birds were no more than thirty feet from where he was sitting. He had a camera, but it was zipped inside his jacket. He decided it would be better to remain still and keep his eye on the birds than to risk scaring them off by removing the camera and snapping the shutter. He later told a reporter, “I knew as soon as I saw them it was something I had never seen before.”

Kulivan debated with himself whether or not he should report his finding. On one hand, of course the birding world would want to know. But on the other hand, wouldn't people think he was crazy, or making a story up to attract attention? It didn't help that it had happened on April Fool's Day. Many people before him had reported seeing Ivory-bills only to be hooted down by the experts. Did he need that? He decided to tell his wildlife professor, Dr. Vernon Wright. Predictably, Dr. Wright grilled him with hard questions, but Kulivan had all the details right, right down to which way the crests on the heads of a male and female curved.

Dr. Wright sent Kulivan to talk to Van, who in turn put him before a panel of very skeptical experts. No one could crack his story. Van thought it was the best Ivory-bill report he had heard in thirty years. “Kulivan either saw a pair of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers,” he said, “or he saw Pileateds and for some reason went nuts ⦠He passed with flying colors.”

Kulivan's report was kept quiet for nearly a year while all logging in the refuge was suspended and state officials searched for Ivory-bills on foot and from the air. But in January 2000, a Jackson, Mississippi, newspaper broke the story, and overnight, bird-watchers from all over the world flocked to Louisiana. Birders filled up local motels and, flipping out credit cards, emptied the stores of film, batteries, cassette tapes, compasses, insect repellent, sunscreen, and snake boots. Then they waded into the

dark waters of the Pearl River. Some played the old Cornell recording on their tape recorders, confusing each other. Some searched in teams, spreading out and communicating by cell phone. One team maintained steady cell-phone contact with a Florida woman who described herself as an “animal communicator.” She said she was tuned in to the spirits of woodpeckers. In the end, even her clients sloshed out with soaked trousers and no images or recordings of Ivory-bills.

dark waters of the Pearl River. Some played the old Cornell recording on their tape recorders, confusing each other. Some searched in teams, spreading out and communicating by cell phone. One team maintained steady cell-phone contact with a Florida woman who described herself as an “animal communicator.” She said she was tuned in to the spirits of woodpeckers. In the end, even her clients sloshed out with soaked trousers and no images or recordings of Ivory-bills.

Van's LSU office became the nerve center of this international sensation. His phone was flooded with reports of Ivory-bill sightings from fifteen states and even Canadaâcold, snowy places far from where Ivory-billed Woodpeckers had ever been. Van knew that the logging would soon resume, but he worried. What if the Pearl really

was

the last home for the species? What if they really were out there? Then one day Van got a call from Anthony Cataldo, an executive representing Zeiss Sports Optics, a binocular manufacturer, volunteering to finance a search for the Ivory-bill at the Pearl. Cataldo wanted Van to put together an all-star team of bird experts from around the world for a thirty-day search. Van chose six searchersâtwo specialists at finding birds in difficult places, three woodpecker experts, and a computer scientist who knew the Pearl River in detail. They rushed to Louisiana, for the world of birding held no greater prize than the rediscovery of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker.

was

the last home for the species? What if they really were out there? Then one day Van got a call from Anthony Cataldo, an executive representing Zeiss Sports Optics, a binocular manufacturer, volunteering to finance a search for the Ivory-bill at the Pearl. Cataldo wanted Van to put together an all-star team of bird experts from around the world for a thirty-day search. Van chose six searchersâtwo specialists at finding birds in difficult places, three woodpecker experts, and a computer scientist who knew the Pearl River in detail. They rushed to Louisiana, for the world of birding held no greater prize than the rediscovery of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker.

Sixty-six years after Allen, Kellogg, Sutton, and Tanner had recorded the Ivory-bill's voice at Camp Ephilus, Cornell University returned to try again. This time technicians from Cornell's Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds placed twelve microphones at equal distances throughout the swamp. Unlike the bulky old sound mirror that Jim Tanner had to place practically in a bird's nest, these were lightweight computerized microphones called acoustic recording units that detected even the tiniest sounds over great distances and stayed on twenty-four hours a day. Without doubt, the Zeiss search would be the best-equipped, best-planned, and best-financed expedition to search for Ivory-bills since the Cornell sound team's mission of 1935.

Early in January 2002, the six searchers moved into a bunkhouse near Slidell, Louisiana, and began preparations for their mission. Then, for the next thirty days, they sloshed through the thirty-five-thousand-acre swamp and also explored a neighboring area almost as large. They hunted in pairs, swatting away the webs of enormous

Banana Spiders as they walked. They were often chest-high in water as they waded across sloughs and creeks. When the water got too deep, they hunted in boats. “Soaking wet” became their normal condition.

Banana Spiders as they walked. They were often chest-high in water as they waded across sloughs and creeks. When the water got too deep, they hunted in boats. “Soaking wet” became their normal condition.

Sometimes they came upon tantalizing signs. Broad sheets of bark dangled in loose strips from the high reaches of several trees. They found Ivory-bill-sized cavities dug out of several others. But by far the most dramatic event of all happened on the eleventh day of the search. On the morning of January 27, four of the searchers heard two loud, ringing cracks echo through the swamp, one right after the other.

Ba-DAM!

Then it happened again.

Ba-DAM!

And again. The Cornell microphones picked them up, too. Could this have been the signature double rap of the Ivory-bill? The searchers clicked their hand-held global positioning system units to fix their locations and charged off in the direction of the sound, but the water became too deep. They never heard the sounds again.

Ba-DAM!

Then it happened again.

Ba-DAM!

And again. The Cornell microphones picked them up, too. Could this have been the signature double rap of the Ivory-bill? The searchers clicked their hand-held global positioning system units to fix their locations and charged off in the direction of the sound, but the water became too deep. They never heard the sounds again.

After a month, the searchers waded out, cleaned the muck off their gear, and faced the world's cameras and microphones. Foreign reporters participated in a global press conference through a satellite hookup. One of the scientists began by reading a statement the six team members had written together. It said: “We have no proof for the presence of the bird in the area, but think it might be there. In view of the good habitat ⦠we recommend more searches in the area.” Weeks later, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology reported that computer analysis of the cracking sounds heard on the eleventh day showed that they were made not by woodpecker bills but by rifles.

Other books

An Accidental Tragedy by Roderick Graham

Shadow on the Sun by David Macinnis Gill

Beauty and the Duke by Melody Thomas

Too Many Traitors by Franklin W. Dixon

The World's Next Plague by Colten Steele

Christmas at Draycott Abbey by Christina Skye

The Dictionary of Homophobia by Louis-Georges Tin

Wasted: An Alcoholic Therapist's Fight for Recovery in a Tragically Flawed Treatment System by Michael Pond, Maureen Palmer

Tarantula by Mark Dawson

Nothing More than Murder by Jim Thompson