The Race to Save the Lord God Bird (14 page)

Read The Race to Save the Lord God Bird Online

Authors: Phillip Hoose

BOOK: The Race to Save the Lord God Bird

13.49Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

WAR IN A BOX

To the Chicago Mill and Lumber Company, World War II came in a box. The armed forces needed boxes to hold airplanes, shells, tanks, medicine, and dry food to be shipped overseas. Overnight, Chicago Mill could sell all the boxes it could make to the

War Department. There was only one problem: with so many young men drafted into service, who would be left to cut the trees?

War Department. There was only one problem: with so many young men drafted into service, who would be left to cut the trees?

EXECUTIVE ORDER 8802

In 1940 the NAACP's magazine Crisis ran a story titled “Warplanes: Negro Americans May Not Build Them, Repair Them or Fly Them, but They Must Help Pay for Them (with Taxes).” Fewer than 1 percent of the jobs in airplane factories were held by blacks. Black leaders threatened to organize a huge march on Washington demanding good, high-paying defense jobs unless President Roosevelt did something about it first.

The pressure worked. On June 25, 1941, President Roosevelt passed Executive Order 8802 setting up the Committee on Fair Employment Practices to ensure that blacks got their share of the factory jobs. Roosevelt said, “There shall be no discrimination in the employment of workers in defense industries or government because of race, creed, color, or national origin.” After that, doors flew open for blacks in shipyards and factories. And many black women and men from southern states like Louisiana walked through them.

The problem was severe in northeastern Louisiana, where there were far more blacks than whites. Before 1940, there were only 5,000 African Americans in all the U.S. Army. By 1944 there were 700,000. The need to manufacture war supplies created factory jobs in northern cities that lured black women and men away from their plows and fields in the South. Between 1940 and 1950, more than a thousand blacks left Madison Parish, many of them laborers who had worked in the woods and fields.

In March 1942, Chicago Mill's president, James F. Griswold, showed up at Audubon House in New York City, finally ready to talk with Baker about the Singer land. The two men bent over maps and talked about how much money it would take to buy Greenlea Bend. The price they came up with to save four thousand acres was about $200,000. The men got along surprisingly well, and the meeting gave Baker a glimmer of hope. “Mr. Griswold has just been with me here at Audubon House,” he wrote to Tanner. “He was most agreeable and sympathetic in his attitude.”

And so, as the clock ticked down the final minutes of the chance to save a big scrap of the Singer Tract, things seemed to be falling into place. Louisiana governor Sam H. Jones came up with $200,000 to buy the land. He joined the governors of Tennessee, Arkansas, and Mississippi in writing a letter to Chicago Mill and the Singer company, urging them to sell their rights so the trees could be preserved. Officials of the Roosevelt Administration agreed to state in writing that the United States didn't need the lumber at the Singer Tract to win the war.

Baker found a publisher to produce a book of Jim Tanner's report on the Ivory-billed Woodpecker so more people could know how important this issue was. With only a few weeks left before he had to leave for the Navy, Jim set up a card table in his

living room and plunked his typewriter on it. He worked day and night to finish his manuscript.

living room and plunked his typewriter on it. He worked day and night to finish his manuscript.

Finally, Chicago Mill consented to an all-or-nothing meeting with everyone who was pressuring it to stop cutting at the Singer Tract. The date was set for December 8, 1943, in Chicago. As the meeting date drew near, Baker ordered an Audubon worker named Richard Pough to quietly slip down to the Singer Tract and look for Ivorybills “so that no one could say there weren't any down there.” Pough's instructions were to avoid all Chicago Mill people if he couldâin effect, he was a spy.

Baker probably woke up on the day of the meeting with a cautious feeling of hope. With the labor shortage and the money that had been raised, maybe the companies would at least sell the rights to Greenlea Bend. But something else was happening that Baker didn't know. Chicago Mill was no longer short of workers in Louisiana. Help had arrivedâfrom an unimaginable place.

Entrance to the Chicago Mill and Lumber Company mill, Tallulah, Louisiana

VISITING WITH ETERNITY

When the last individual of a race of living things breathes no more, another heaven and

another earth must pass before such a one can be again.

another earth must pass before such a one can be again.

âWilliam Beebe (1906)

T

WELVE-YEAR-OLD BILLY FOUGHT SCUFFED HIS BOOT IN THE RED DUST AS HE WAITED for his school bus to come where Sharkey Road crossed the Chicago Mill railroad tracks. It was a late autumn day in 1943. The leaves were already starting to turn. Billy and his ten-year-old brother, Bobby, were new to the countryside. After their mother had died, their dad had moved them from Tallulah to take a job driving a spur train for the Chicago Mill and Lumber Company. Now they were “swamp rats,” living in Chicago Mill's portable logging camp and playing and fishing in the bayous. But they still had to go to school, and so there they stood, alone, waiting for the bus.

WELVE-YEAR-OLD BILLY FOUGHT SCUFFED HIS BOOT IN THE RED DUST AS HE WAITED for his school bus to come where Sharkey Road crossed the Chicago Mill railroad tracks. It was a late autumn day in 1943. The leaves were already starting to turn. Billy and his ten-year-old brother, Bobby, were new to the countryside. After their mother had died, their dad had moved them from Tallulah to take a job driving a spur train for the Chicago Mill and Lumber Company. Now they were “swamp rats,” living in Chicago Mill's portable logging camp and playing and fishing in the bayous. But they still had to go to school, and so there they stood, alone, waiting for the bus.

The Ivory-bill made its last stand within the Singer Tract, at John's Bayou, once the site of Camp Ephilus and the birthplace of Sonny Boy

Billy looked up when he heard a motor. Instead of the bus, he saw a black truck, filled with men. The truck stopped, and about twenty husky young white men were ushered out by armed guards. The men wore identical blue jumpsuits, navy-blue caps, and armbands with the big letters “PW.” Whatever they were saying to each other, it sure didn't sound like English.

Billy had heard the grownups talking about this, but it hadn't seemed possible. German soldiers, the enemyâ

Nazis

âhad come to work in their woods. But it was true. Day after day, the truck arrived at the crossroads and the young men jumped

out, some carrying hand-carved wooden lunchboxes. Enemy soldiers from the very same army that was trying to kill American soldiers halfway around the worldâsoldiers from Tallulah, evenâstood around the clearing, stretching and chatting for a few minutes each day until they were led into the woods or sent out to work on the railroad tracks. One day, one of them actually beckoned to Bobby and offered him a candy bar. As Bobby slowly reached out his hand for it, Billy grabbed his arm. “Don't eat it!” he hissed. “It might be poison!” The German got down on one knee to look directly at Bobby. He said, in English, “Please take it. I have a boy at home, too. You remind me of him.”

Nazis

âhad come to work in their woods. But it was true. Day after day, the truck arrived at the crossroads and the young men jumped

out, some carrying hand-carved wooden lunchboxes. Enemy soldiers from the very same army that was trying to kill American soldiers halfway around the worldâsoldiers from Tallulah, evenâstood around the clearing, stretching and chatting for a few minutes each day until they were led into the woods or sent out to work on the railroad tracks. One day, one of them actually beckoned to Bobby and offered him a candy bar. As Bobby slowly reached out his hand for it, Billy grabbed his arm. “Don't eat it!” he hissed. “It might be poison!” The German got down on one knee to look directly at Bobby. He said, in English, “Please take it. I have a boy at home, too. You remind me of him.”

The German on the other end of that candy bar had seen a lot of the world in the past two years. He had been captured in North Africa, where he had fought as part of an elite German unit called the Afrika Korps. Its mission was to conquer Egypt and seize control of the Suez Canal between the Red Sea and Mediterranean so that the Axis forcesâGermany, Japan, and Italyâcould command the oil fields of the Middle East.

Instead, caught in a trap between U.S. and British forces, the German soldiers were defeated. Many were killed and a multitudeâhundreds of thousands of Axis troopsâwere captured. Since British jails were already full, the British asked the United States to take them, and the War Department reluctantly agreed.

The prisoners were marched onto big, flat-decked “Liberty Ships” that sailed from North Africa to Scotland and then on to Liverpool, England. Most prisoners probably assumed they had reached their destination, but there was yet another body of water to crossâthe Atlantic. Weeks later, when the great ships approached New York City, all prisoners were ordered on deck to see the Statue of Liberty and the giant skyscrapers take shape on the western horizon. Many stared in open-mouthed disbelief, for their officers had told them New York had been destroyed. Some thought it was a trickâa Hollywood film set.

In New York the men were put on trains and transported under guard to prison camps throughout the United States. It surprised some German prisoners that they were allowed to sit in cars reserved for whites, while blacks, who were fighting for America, sat in segregated cars. In all, about twenty thousand prisoners of war journeyed to Louisiana, where they were then sent to one of four main camps. On

August 14, 1943, the first three hundred Afrika Korps prisoners, still tanned from the African sun, marched into Camp Ruston, a prison camp about forty miles from Tallulah.

August 14, 1943, the first three hundred Afrika Korps prisoners, still tanned from the African sun, marched into Camp Ruston, a prison camp about forty miles from Tallulah.

The next month, the War Department announced that the POWs would be available to Louisiana planters and other companies that needed laborers. Employers would have to pay them a small salary, transport them between their prison camps and the work sites, provide guards, and feed them. The Tallulah fairground was wrapped in barbed wire for 505 German prisoners, who promptly set up their own kitchen, bakery, and library.

Chicago Mill was one of the first companies to snap up the cheap labor, sending trucks to pick up the POWs at the camp and drive them out to the Singer Tract each morning. And that was why Bobby Fought, standing on a red dirt road near Tallulah, Louisiana, found himself on the other end of a candy bar offered by a Nazi soldier.

Some of the German prisoners picked up crosscut saws and took on the hard work usually done only by black workers. Others chopped logs or loaded freight cars or worked on the railroad. Those with professional training became mechanics and engineers. None of them had ever seen forests anything like the thick, tangled woods of the South. One complained, “When we Germans hear the word âforest' we think of the beauty of our homeland ⦠[Here] a thicket of thorns blocks the way to the trees. You have to hack your way in.” And they hated the insects. Wrote another, “Who does not know these little red stitches ⦠itching and biting like hundreds of ants? ⦠There seems to be no medicine against the bite of a spider like a point of a needle.”

THE ENEMY AMONG US

About 375,000 German prisoners worked and lived in forty-four states between 1943 and 1946. They labored in canneries, foundries, quarries, forests, mills, and mines. They picked cotton, dug potatoes, and harvested corn.

They marched into camps as hardened Nazis, but most became less and less militant as the months wore on. They were fed well and quickly gained weight. They seemed to like outdoor work and were glad not to be in prison. Guiltily, local teams played against them in football and soccer. Prison officials, at first nervous, relaxed their guard and let them supervise their own men at work. The POWs baked good bread, which they sold at prison stores. Americans stood in line to buy the things they carved. In Louisiana, one prisoner carved a fine chess set. At Tallulah, a German made a fine violin from scrap. At Camp Livingston, one man made a collapsible model house. Few tried to escape, and many returned to the United States to live after the war.

The Germans were like a gift from heaven to the Chicago Mill and Lumber Company. Now it could make money three ways in one project: it could clear the Singer Tract with workers who were practically free; it could sell as many boxes as it could make to the ravenous War Department; and it could sell the cutover land to rural

families who wanted cheap farmland. Chicago Mill didn't even have to clean up the mess it had made. “The waste, you couldn't believe it,” recalls Gene Laird. “If you stood at a cut-down tree and it didn't measure three feet around, they'd just leave it on the ground.”

families who wanted cheap farmland. Chicago Mill didn't even have to clean up the mess it had made. “The waste, you couldn't believe it,” recalls Gene Laird. “If you stood at a cut-down tree and it didn't measure three feet around, they'd just leave it on the ground.”

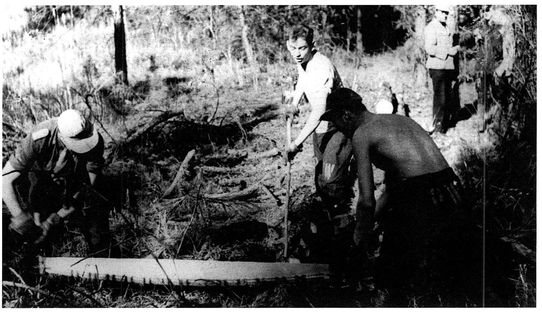

German prisoners of war cut trees in the South

With new muscle from the prisoners, the 45-foot-long conveyor belt that delivered logs to a giant toothed blade at the Tallulah sawmill ran twenty-four hours a day. Log by log, two hundred years of southern history was ground into yellow dust. The mysterious, howling Tensas swamp forest, nightmare of planter families, was tamed by a single machine. From time to time the blade jammed on balls of shot from the Civil War still buried in the logs coming through. When that happened, the log was tossed aside, a switch was flicked, and the blade ground on.

Against those whirring teeth the last great Ivory-bill forest collapsed day by dayâand with it went Chicago Mill's interest in saving even a single tree.

“WE ARE JUST MONEY GRUBBERS”

At noon on Wednesday, December 8, 1943, a group of men stomped in from the Chicago winter, squirmed out of their overcoats, placed their hats on racks, and shuffled

into Chicago Mill's downtown boardroom. Seated around the table were important representatives from the federal government, the southern states, the Audubon Society, and the Singer company. After introductions, the group quickly settled down to business. Audubon president John Baker's report tells what happened next: “[Chicago Mill] refused to cooperate in any way, and said that it would not enter into any deal unless forced to. The Chairman said, among other things, âWe are just money grubbers. We are not concerned, as are you folks, with ethical considerations.' They would not help in any way with the creation of a park or refuge âunless forced to do so.'”

into Chicago Mill's downtown boardroom. Seated around the table were important representatives from the federal government, the southern states, the Audubon Society, and the Singer company. After introductions, the group quickly settled down to business. Audubon president John Baker's report tells what happened next: “[Chicago Mill] refused to cooperate in any way, and said that it would not enter into any deal unless forced to. The Chairman said, among other things, âWe are just money grubbers. We are not concerned, as are you folks, with ethical considerations.' They would not help in any way with the creation of a park or refuge âunless forced to do so.'”

The Singer company's position was the same. It no longer cared about the trees on its propertyâwhat happened to them was up to Chicago Mill. Singer wasn't even making sewing machines during the warâits manufacturing equipment was now cranking out gun sights and triggers.

The bad news didn't stop there. Richard Pough, the man Baker had sent to Louisiana to find Ivory-bills, telegrammed that after three weeks of searching he hadn't been able to find a single bird. What he

had

seen turned his stomach. “It is sickening to see what a waste a lumber company can make of what was a beautiful forest,” Pough wrote to Baker. “I watched them cutting the last stand of the finest sweet gum on Monday. One log was six feet in diameter at the butt.”

had

seen turned his stomach. “It is sickening to see what a waste a lumber company can make of what was a beautiful forest,” Pough wrote to Baker. “I watched them cutting the last stand of the finest sweet gum on Monday. One log was six feet in diameter at the butt.”

But three weeks later, as freezing rain popped onto the forest floor and spread a fine glaze of ice over the bare limbs above, Pough's luck changed. From a logging road at John's Bayou, he heard at last the “kent, kent” cry he had been awaiting for so long. Hopping over tractor gashes, he chased the sound through a wasteland of mashed limbs to an ash tree in a small section of the forest still not cut. He raised his eyes and finally found his trophyâa female Ivory-billed Woodpecker. Her well-used roost tree was riddled with six large holes. Though it was well into January, she still had no mate.

Pough sadly watched the bird feed for a while, then hiked into Tallulah to telegram Baker in New York. “I have been able to locate only a single female and feel reasonably sure there are no other birds here,” he dictated. He soon followed it with another message: “I really fear the area will be cut any day.”

Baker kept trying to stop the logging and save the land. He wrote letters to magazine

writers and politicians, hoping to put pressure on Chicago Mill. Even if the Ivory-bills were almost gone, he argued, wouldn't a scrap of the last virgin forest left in the Mississippi River delta still be worth saving? Didn't we owe that to future generations of southerners, at least? But the nation could hear only war. Chicago Mill's saw whined on without pause as more and more boxcars, sometimes fifty at a time, lined up for the wood. The War Department needed plywood cut from sweet gums to make gasoline tanks for jet fighters. They wanted boxes to hold shells. Even the British army had a special need for the last Ivory-bill forest. A history of the Chicago Mill and Lumber Company says, “The Tallulah plant was so busy making tea chests for supplying the English army with its tea that they had a regular production line which ended in three box cars sitting side by side on the railroad siding tracks.”

writers and politicians, hoping to put pressure on Chicago Mill. Even if the Ivory-bills were almost gone, he argued, wouldn't a scrap of the last virgin forest left in the Mississippi River delta still be worth saving? Didn't we owe that to future generations of southerners, at least? But the nation could hear only war. Chicago Mill's saw whined on without pause as more and more boxcars, sometimes fifty at a time, lined up for the wood. The War Department needed plywood cut from sweet gums to make gasoline tanks for jet fighters. They wanted boxes to hold shells. Even the British army had a special need for the last Ivory-bill forest. A history of the Chicago Mill and Lumber Company says, “The Tallulah plant was so busy making tea chests for supplying the English army with its tea that they had a regular production line which ended in three box cars sitting side by side on the railroad siding tracks.”

Several members of the Audubon Society's New York City staff journeyed to John's Bayou as if they were saying farewell to a friend with a terminal illness. Baker himself went to see the bird, as did Roger Tory Peterson. Don Eckelberry, who illustrated Audubon field guides, bundled up his outdoor clothes and sketch pads and boarded a southbound train as soon as he read Richard Pough's disastrous news. Eckelberry was determined to sketch and paint the last Ivory-bill before it died.

Eckelberry arrived in Louisiana in April 1944. He was welcomed by Jesse Laird, a local warden who had helped Jim Tanner in the final year of his study. One late afternoon, Laird and Eckelberry reached the ash tree where the female Ivory-bill had been roosting every night. The men sat silently on a log and waited as sunlight slipped away. At 6:25 they heard her rap on a tree in the distance. There was no answer. She called for about twenty minutes more, as if beckoning a mate. Finally, wrote Eckelberry, “she came trumpeting into the roost, her big wings cleaving the air in strong, direct flight, and she alighted with one magnificent upward swoop. Looking about wildly with her hysterical pale eyes, tossing her head from side to side, her black crest erect to the point of leaning forward, she hitched up the tree at a gallop, trumpeting all the way.”

With too little light left to sketch, Eckelberry just watched, awestruck, until dark. He felt like he was staring at eternity. This single unmated female was all that remained of the Lord God bird that had commanded America's great swamp forests for thousands of years. She was the sole known remainder of a life-form that had predated

Columbus, or Christ, or even Native Americans. The arrow-like flight, the two-note whacks that echoed through gloomy forests, the ability to peel entire treesâall that was left of these ancient behaviors was now right before his eyes.

Columbus, or Christ, or even Native Americans. The arrow-like flight, the two-note whacks that echoed through gloomy forests, the ability to peel entire treesâall that was left of these ancient behaviors was now right before his eyes.

Eckelberry returned to the tree most days for the next two weeks, riding to the Sharkey plantation in Jesse Laird's jeep and then hiking half a mile into the forest with his paper, brushes, paint, pencils, sketch pads, and binoculars. He sketched at dawn and dusk, when the bird was at her roost tree, because he couldn't begin to keep up with her as she flew over the forest. He liked to think he was “waking up with her” and “putting her to bed.” Sometimes he lost track of time until he realized he was sitting in darkness. Then he hoped the moon would come up bright so he could find his way home.

On one of those days, Billy and Bobby Fought were skipping stones off the bridge at the Sharkey plantation road with two other boys when Mr. Laird's jeep drove up. The door opened and a stranger got out, carrying a huge sketch pad and a box of pencils. He was slender and dignified-looking, and he walked with a limp. The boys clustered around. He introduced himself as Don Eckelberry and said he was hiking to a tree to sketch the last Ivory-billed Woodpecker. Did they want to go with him? Mr. Laird said they should, it was their chance to see a great bird maybe no one would ever see again. “You'll have to be quiet,” Mr. Laird said. The Fought brothers quickly stepped forward as the other boys turned back to throwing rocks. “Will it be okay with your parents?” the stranger asked. “Yessir,” replied Billy Fought. “We don't have to ask when to go into the woods.”

So the two boys and Eckelberry waded and splashed to the gnarled ash tree and sat down on a log, a boy on either side of the artist. He sketched everything in sight as they waited. He drew the ash tree, a wolf, the flowers, the birds, even Bobby Fought. He couldn't seem to stop, and they had never seen anyone who could draw so fast or so well. And then, around suppertime, the air seemed to stand still as the Ivory-bill winged in. She rapped on the tree with her gleaming beak, hopped up, went into the hole, stuck her head back out as if to say good night, and then disappeared. The artist told the brothers that he hoped they could understand how special this moment was and that he hoped somehow they would remember it always, even though they were young. He drew as he spoke, and the great bird seemed to come to life on his pad.

“I've never been quite the same since,” says Billy Fought, now in his seventies. “I'll never forget Mr. Eckelberry, or that bird, or that day, as long as I live.”

“I've never been quite the same since,” says Billy Fought, now in his seventies. “I'll never forget Mr. Eckelberry, or that bird, or that day, as long as I live.”

Other books

Otherlife Dreams: The Selfless Hero Trilogy by William D. Arand

Crash by Vanessa Waltz

Delta Force Desire by C.J. Miller

If I Could Be With You by Hardesty, Mary Mamie

’Til the World Ends by Julie Kagawa, Ann Aguirre, Karen Duvall

Tombstone by Jay Allan

The Epherium Chronicles: Echoes by T.D. Wilson

The Man in Lower Ten by Mary Roberts Rinehart

The British Lion by Tony Schumacher

The Devil's Soldier by Rachel McClellan