The Race to Save the Lord God Bird (11 page)

Read The Race to Save the Lord God Bird Online

Authors: Phillip Hoose

HARD TRAVELING

For the next three weeks Tanner drove, hiked, galloped, and waded around Florida chasing leads, scribbling notes, leaving his pictures behind, and trying not to get frustrated. The Suwannee had a promising habitat, but no Ivory-bills. The best lead yet took him to a forest near Brooksville, Florida, where an Ivory-bill had been reported only the year before. Tanner searched the area with two local men and at last found a sign: “a dead pine from which the bark had been completely scaled, apparently the work of an Ivory-bill.” Tanner assumed the bird was only passing through, though, since the habitat didn't seem good enough for nesting birds.

On March 17 he took off west for Louisiana and the Singer Refuge, the one place where he knew he could actually find Ivory-bills. Two items of good news awaited him: J. J. Kuhn, the woodsman who had guided the Cornell sound team so expertly before, was available and eager to help. Just as happily, Tanner and Kuhn could use the Singer Manufacturing Company's cabin in the woods as a base of operations. That meant they could stay in the woods all the time except when they had to go into town for supplies.

Tanner and Kuhn concentrated their search on the east side of the Tensas River. On March 26 they finally spotted a pair of adult Ivory-bills winging swiftly through the flooded backwater called John's Bayou, and after four days of hard searching Tanner found their nest, chiseled in the top of a sweet gum. All day long the parents took turns shuttling long white grubs to a single open-mouthed baby, who constantly yapped for food.

The very next day, the little bird hopped up onto the lip of the nest hole, steadied itself, spread its wings, and leaped into its first flight. It never returned to the nest again, and the family's address shifted to a tree about a quarter mile away where they sleptâor “roosted”âtogether each night.

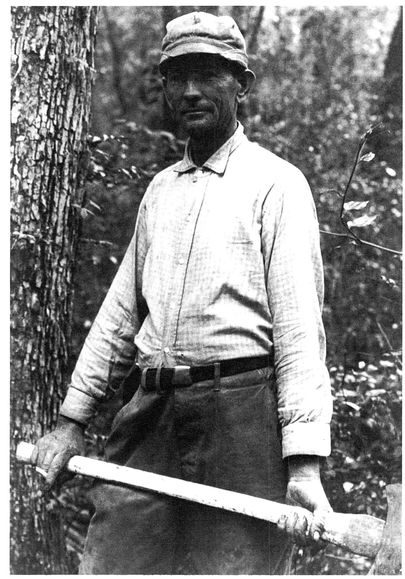

J. J. Kuhn, warden of the Singer Refuge and Tanner's indispensable companion

“[The young bird ] flew well from the start,” Tanner wrote proudly. “The family hunted together close to the nest tree for the next two months. The youngster grew stronger and more independent every day. Within a month it could join its parents on

food-finding trips two miles away from their home tree. By mid-July it was nearly as big as its mother and father, a powerful flyer and a mighty hunter of grubs.” It still called to be fed, though, as young birds often do. Tanner found himself delighted by the prowess of this young bird, but worried that the family had produced only one egg. “This pair of birds gave no indication of nesting a second time,” he wrote, “even though they nested so very early.”

food-finding trips two miles away from their home tree. By mid-July it was nearly as big as its mother and father, a powerful flyer and a mighty hunter of grubs.” It still called to be fed, though, as young birds often do. Tanner found himself delighted by the prowess of this young bird, but worried that the family had produced only one egg. “This pair of birds gave no indication of nesting a second time,” he wrote, “even though they nested so very early.”

Throughout May and June, Tanner and Kuhn combed the forest for more Ivory-bills. The daily hikes installed a mental map of the forest in Tanner's head. He came to know where the waterways called bayous emptied into the forest, where the lakes were, and how the forest trees changed when the ground got lower or higher, wetter or drier. The Ivory-bills nested and slept in sweet-gum and oak trees that sprouted from dry ridges that had long ago been banked up by the Mississippi's floods. Tanner called them “first bottoms.”

Kuhn and Tanner usually split up so that they could cover twice as much ground. They searched mainly in the morning, when the birds were most active. Tanner's strategy was to stop walking and listen about every quarter mile, since the Ivory-bill's call carried about half a mile. He always heard Ivory-bills before he saw them. When he wasn't searching for birds, he was working on other parts of his research project, doing things like counting trees, collecting and inspecting grubs, scouting new locations, and investigating the biology and ecology of the Ivory-bill in countless other ways.

Sometimes he just sat still. As a young boy, he had practiced sitting still outdoors for long periods of time. Now this was helping him in his profession. As he sat and listened, swatting bugs, taking notes, trying not to scratch his poison ivy welts, daydreaming and dozing every now and then, he occasionally tried to imitate the Ivory-bill's call to see if the birds would answer. They never did. Once he tooted through the mouthpiece of a saxophone. No luck. But from time to time an Ivory-bill would call on its own from somewhere way off in the forest, sending him springing to his feet and tearing off after it, through the underbrush.

During the winter and spring of 1937, Tanner and Kuhn found evidence of adult Ivory-billed Woodpeckers in seven different parts of the Singer Tract. Since adult Ivory-bills mated for life and stayed together all year round, Tanner assumed there

were seven different nesting pairs, even though he saw only one young bird the whole time. Another parent was seen winging across a lake with a grub dangling from its bill, which almost certainly meant there was a young bird to be fed, but they couldn't find the nest and never saw a nestling.

were seven different nesting pairs, even though he saw only one young bird the whole time. Another parent was seen winging across a lake with a grub dangling from its bill, which almost certainly meant there was a young bird to be fed, but they couldn't find the nest and never saw a nestling.

Tanner kept wondering why all those adults produced so few young birds. Was Doc right about inbreeding? Were they tormented by mites? Or was it something else they hadn't even thought of? After the small Ivory-bill family Kuhn and Tanner found on March 26 had abandoned its nest tree, Tanner shinnied high up the sweet gum and inspected the nest. Once again there was no evidence of parasites or mites, nor were there signs of struggle. The disappearing Ivory-bills were still a mystery.

When summer came, broad leaves made treetops almost impossible to see and the air filled with swarming mosquitoes. Tanner rolled up his bedroll, packed his boots, and got ready to hike out to Tallulah and head home. But just before he left, he and Kuhn heard news that hit them both hard: the Singer company had sold six thousand acres of its land to a lumber company, and logging had already started. The land was on the west side of the Tensasânot the best Ivory-bill habitat in the forest, but now the lumbermen had their feet in the door. Even worse, Singer had sold the rest of the west side to the much bigger Chicago Mill and Lumber Companyâwhich had a major sawmill in Tallulah. Singer was even allowing an oil company to drill test wells in prime Ivory-bill habitat.

Tanner said goodbye to Kuhn on June 29 and spent another month tracking leads in Louisiana and South Carolina before he turned north toward home. Back at Cornell, he sorted through the hundreds of pages of notes he had compiled, and began to reflect on what he had learned so far.

In his first season of sleuthing, he had been able to find Ivory-bills only at the Singer Tract. There was still promising habitat at Big Cypress Swamp and the lower Suwannee River, both in Florida. These sites merited follow-up visits. Four other places looked good, too, but less so. The birds at Singer were not reproducing well, and he still didn't know why. But he now knew more about the kinds of trees the birds liked, what they ate, and how much space a nesting family seemed to need.

Casting a shadow over everything was the sale of Ivory-bill habitat at Singer. Tanner didn't let his emotions show easily, but there was desperation in his year-end report

to John Baker of the Audubon Society. Time was running out. “Those woods should be

preserved,”

he wrote. “That area should be a national monument, and I strongly recommend that a movement be started towards that goal, even though the lumbering interests and possibility of oil present difficulties.”

to John Baker of the Audubon Society. Time was running out. “Those woods should be

preserved,”

he wrote. “That area should be a national monument, and I strongly recommend that a movement be started towards that goal, even though the lumbering interests and possibility of oil present difficulties.”

Looking back at that winter and spring, Tanner knew there were still many more questions than answers, but one thing was certain: he had done some hard traveling. He wrote a tribute to his indestructible Ford that might well have reminded him of himself. “It has been the first car to break a way over many a muddy road,” he said. “It has had several springs broken, mufflers knocked off and running-boards knocked loose, bumpers broken on trees, and the front axle bent. But it still runs.”

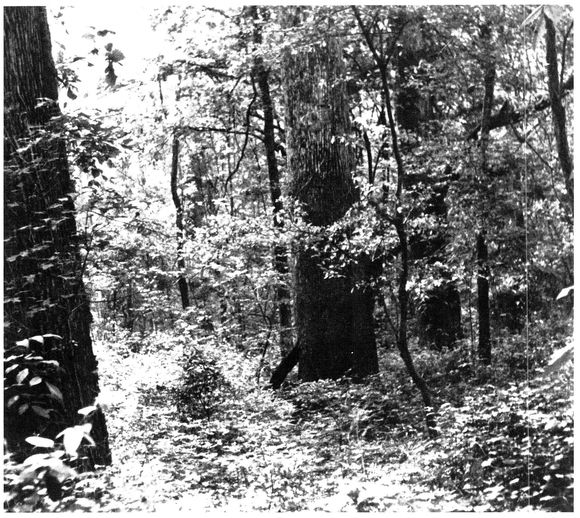

The Singer Tract was the last significant scrap of a vast riverbottom forest that once covered millions of acres

THE LAST IVORY-BILL FOREST

The Ivory-bill has frequently been described as a dweller in dark and gloomy swamps, has been associated with muck and murk, has been called a melancholy bird, but it is not that at all ⦠The Ivory-bill is a dweller of the tree tops and sunshine; it lives in the sun ⦠in surroundings as bright as its own plumage. It is true that the man trying to watch and follow these birds is probably in the shade and mud, among the fallen trees and running vines, but that does not affect the Ivory-bill in the least. He stays above all that, and is a handsome, vigorous, graceful bird.

âJames Tanner

F

OUR MONTHS LATER, TANNER WAS BACK IN THE SOUTH. HIS RESEARCH OF THE PREVIOUS spring had narrowed down the number of likely habitats for Ivory-bills, and there was no time to waste. The place he wanted to explore most was a swamp around the Santee River in South Carolina. Museum specimens and local reports left no doubt that many Ivory-bills had once lived there. Local experts confidently predicted that eight to twelve nesting pairs still remained.

OUR MONTHS LATER, TANNER WAS BACK IN THE SOUTH. HIS RESEARCH OF THE PREVIOUS spring had narrowed down the number of likely habitats for Ivory-bills, and there was no time to waste. The place he wanted to explore most was a swamp around the Santee River in South Carolina. Museum specimens and local reports left no doubt that many Ivory-bills had once lived there. Local experts confidently predicted that eight to twelve nesting pairs still remained.

By now the Ivorybill was to be found only in one place: the Singer Tract in northeastern Louisiana

Early in December, Tanner and a guide pulled on their boots and set out to comb every part of the Santee swamp for Ivory-bills. Eleven days later they came back disappointed. While they had seen a few stripped trees, Tanner wasn't sure Ivory-bills had done the work. And they hadn't heard a single call.

The Santee search made Tanner rethink how much habitat Ivory-bills really needed. “I believe [the local experts] have underestimated the range of the birds, and so overestimated the numbers,” he wrote. In short, he feared that there wasn't nearly enough food for eight to twelve pairs in a forest the size of the Santee's. He thought

back to the Ivory-bill family he had studied in the spring at the Singer Tract. They were nomads. Within a month, even the little bird had been able to fly two miles from its home tree in search of food. He realized that it must take a lot of territory to contain enough food for a family of Ivory-bills. The Santee was less than half the size of the Singer Tract. Tanner figured it was big enough for only two, maybe three, pairs at most.

back to the Ivory-bill family he had studied in the spring at the Singer Tract. They were nomads. Within a month, even the little bird had been able to fly two miles from its home tree in search of food. He realized that it must take a lot of territory to contain enough food for a family of Ivory-bills. The Santee was less than half the size of the Singer Tract. Tanner figured it was big enough for only two, maybe three, pairs at most.

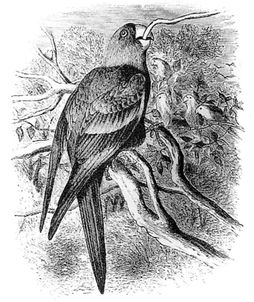

THE CAROLINA PARAKEET

Southern U.S. forests once teemed with emeraldgreen parakeets sporting a bold yellow streak where the wing met the body and a bloodred patch around the eye. Audubon said they were so abundant that they covered orchards “like a brilliant coloured carpet.” Now the species is extinct. Why? Farmers killed them because they ate fruit. Market hunters shot, stuffed, and sold them to collectors. Hatmakers loved the green plumes, and hunters found the birds easy targets. When one bird lay dead on the ground, others in a flock often joined it, making themselves targets, too. The last Carolina Parakeet, Inca, died in the Cincinnati Zoo in 1918.

With this ominous new theory, Tanner gunned the engine of his Ford and swung toward Louisiana, racing through the Georgia hills and across the Mississippi to Tallulah in a single day. By dusk Tanner and J. J. Kuhn were walking single file long the slippery trail to their cabin, balancing sacks of groceries on their shoulders as they picked their way around mud-holes and stepped over logs.

Beginning at dawn the next day, Tanner explored the Singer Tract day and night. Step by step he learned where the bayous ran and how the forest changed from its flat soggy bottom, laced with vines, to its drier ridges. He came to sense the subtle changes of the seasonsâthe lengthening of shadows, the fragrance of blossoming vines, the smell of wet leaves, and the steady electric hum of insects. Finally these patterns converged into a picture of the whole magnificent forest.

Tanner's visits to other swamps in the South had usually been disappointing because loggers had sliced the forests up into small patches. Less than halfway through his study, he began to suspect that the Singer Tract was the last big uncut swamp forest left in the entire Mississippi deltaâmaybe in the whole South. The Singer Tract was the one forest that looked and felt and smelled and sounded as it must have thousands of years before. There was a good chance that every single species that had ever lived in this forest was still there except for the Carolina Parakeet and the Passenger Pigeonâboth extinct. Everything elseâfrom Ivory-bills, panthers, and wolves to grubs, mites, and frogsâwas still there.

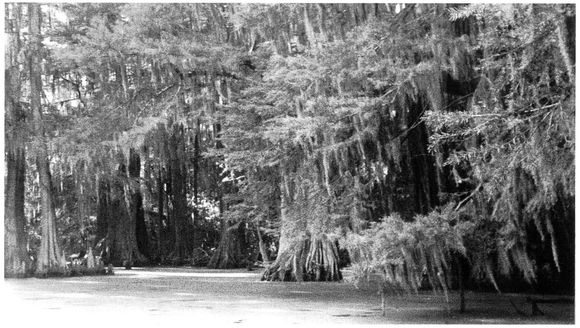

Feather-topped cypress trees fringed the lakes inside the Singer Tract

Tanner was beginning to realize that in order to understand the Ivory-bill's life history, and to save it at the Singer Tract, he had to know the forest completely, to understand it as a single colossal organism throbbing with life. So the whole forest became Tanner's lab, and it fascinated him as much as any species within it, even the Ivory-bill. Often he began hiking before the sun rose and was still out after dark.

Winter was by far Tanner's favorite season. Ivory-bill calls carried a long distance through the leafless forest, and he could spot the birds more easily when they flew through the bare limbs. Plus, there were no mosquitoes or snakes. One winter morning he made his way to an Ivory-bill roost tree while it was still dark, hours before the woodpeckers would be active. Plumping up a cushion of palmetto fronds, he settled himself against a tree to hear the forest wake up. It was great entertainment, he thought, and he didn't even need a ticket.

Just as the first pink stripe appeared behind the black-silhouetted trees, Barred Owls signed off the night shift with their final

“Who cooks for you, who cooks for you

-

call”

hoots. The spreading sunlight brought the day crew to life, singer by singer and song by song.

“Who cooks for you, who cooks for you

-

call”

hoots. The spreading sunlight brought the day crew to life, singer by singer and song by song.

THE RED WOLF

A Red Wolf can be any color from tan to black. Smaller than its cousin the Gray Wolf, it once hunted deer and smaller mammals in forests, marshes, and swamps from Pennsylvania to Texas and in southeastern states. Many were shot and trapped early in the twentieth century as suspected killers of cows and sheep. At the same time, their habitat was cleared and drained.

By the late 1930s, only two populations remained in the United States, including some at the Singer Tract. In 1967, the Red Wolf was declared endangered. Six years later, with the species nearing extinction, biologists captured 14 wolves so they could breed in safe, zoo-like situations. Now there are 270 to 300 Red Wolves, of which 50 to 80 live in the wild.

Brown Thrashers led off the dawn chorus with a hoarse, once-repeated

churr

that welled up from the brambles. White-throated Sparrows chimed in next, with a high melody whose first four notes sounded like “Here comes the bride.” Then the amazing Winter Wrens burst onto center stage, stub-tailed midgets who threw back their heads and belted out the longest song of any bird, rattling their entire frames with the effort. By the time the late-sleeping Ivory-bills finally appeared at their hole to preen their feathers, the forest was bathed in light. By then, Tanner noted, seven other woodpecker species had already called.

churr

that welled up from the brambles. White-throated Sparrows chimed in next, with a high melody whose first four notes sounded like “Here comes the bride.” Then the amazing Winter Wrens burst onto center stage, stub-tailed midgets who threw back their heads and belted out the longest song of any bird, rattling their entire frames with the effort. By the time the late-sleeping Ivory-bills finally appeared at their hole to preen their feathers, the forest was bathed in light. By then, Tanner noted, seven other woodpecker species had already called.

Sometimes surprise guests appeared during his silent vigils. One December morning Tanner was seated on the ground, listening for Ivory-bills, when the vines in front of him rustled and the stiff palmetto fronds gave way to something big and

solid. At first the glossy black back that passed slowly before his eyes seemed to belong to a small horse. Then, suddenly, he realized it was a wolf walking along a log. When it plopped silently to the ground and vanished into a thicket, Tanner raised himself to a half crouch so he could see better. The wolf came out of the brush and passed slowly across a clearing maybe thirty steps away. “He was handsome, powerful ⦠with a deep chest and a lean belly, self confident, alert ⦠black from tip to tail,” Tanner wrote. Cupping his hands, Tanner tried to squeak like a wounded bird to catch the wolf's attention, but it trotted off.

The forest became silent and still at midday, when creatures active in daylight hours seem to take a break. The forest pulse quickened again at dusk and stayed brisk until sundown, which ushered in a whole new cast of characters. One night Tanner rowed a small wooden boat out into the middle of a lake, put his oars at rest, and remained silent as he scanned the moonlit water. “The forest stretched away for miles from the black wall of trees surrounding the lake,” he later wrote. “The air shook with noise ⦠The chorus of frogs came from all sides ⦠loudest by weight of numbers were the tiny cricket frogs on the floating duckweed ⦠sitting and beating out their rasping notes.” He flicked on a flashlight. The beam swept across the surface of

the water until it caught “a glowing coal that burnt for a moment and then went outâthe eye of an alligator that sank beneath the surface.”

the water until it caught “a glowing coal that burnt for a moment and then went outâthe eye of an alligator that sank beneath the surface.”

Day or night, poisonous snakes were a huge worry, especially around Greenlea Bend. Timber Rattlesnakes slithered out from their winter dens just as spring covered up the foot trails with vines, leaves, and brambles. The “thick-bodied water moccasins” and Copperheads that Theodore Roosevelt had seen on his hunting trip were still there, too, and plenty of them. Since Tanner and Kuhn couldn't look up for birds and down for snakes at the same time, there were many unscheduled meetings. Once, as Kuhn went charging through a thicket of vines after a bird, his boot came down on a rattler. The unmistakable sound sent him leaping in the only direction he couldâstraight up. Then, penned in by brambles on all sides, he landed on the only place he couldâstraight down. The snake was still there, rattling away. Heart pounding, Kuhn jumped again, with the same result, and kept on jumping until the snake darted away.

In spring and summer, the two men wore long-sleeved shirts with all the buttons closed tight to the neck and the collars turned up, and sometimes they wore their hats jammed down over their ears. But still the insects bit and stung them. Annoying as it was, it gave them something in common with all the other warm-blooded creatures of the forest, and they had no choice but to accept it.

The most awesome event in the woods occurred when one of the giant trees fell. This usually happened after a hard rain, when a grand old monarch's soaked crown became so heavy that the trunk could not hold it up any longer. Then, as Tanner wrote, “the quiet of the woods would suddenly be broken by a resounding crack ⦠then a series of loud snaps merging into a roaring crescendo as the tree crashes downwards to hit the earth with a dull, echoing boom. The echoes quickly die away, but the forest still seems to hold its breath until gradually the birds resume their song, the normal quiet sounds return, and the listener collects his scattered thoughts.”

In the evenings, Kuhn and Tanner ate their supper together by a kerosene lamp on the cabin's screened-in porch. Since they often split up during the day, they used the night to catch up. “We talked ⦠just as Mark Twain's river pilots endlessly discussed the details of the river's course,” wrote Tanner. “Although learning of the Ivory-bill and its life history was our goal, the forest was our working place and we had to know itâ[how] to find our way, to travel quickly and to know where to hunt.”

Other books

Amanda Ashley by After Sundown

Outback Flames: Australian Rural Romantic Suspense by Brandyn, Suzanne

In the End by Alexandra Rowland

Love Spell by Crowe, Stan

Under the Net by Iris Murdoch

A este lado del paraíso by Francis Scott Fitzgerald

Against the Night by Kat Martin

Trained by Three Panthers [Caves of Correction 3] by Cara Adams

Captain Nobody by Dean Pitchford