The Race to Save the Lord God Bird (8 page)

Read The Race to Save the Lord God Bird Online

Authors: Phillip Hoose

SHOOTING WITH A MIKE

With the expansion of vision beyond the gunsight, an entire new world unfolded like the opening of a bud of a most wonderful, beautiful flower.

âDr. Boonsong Lekagul, ornithologist from Thailand

T

HE CORNELL TEAM, MINUS BRAND, WHO WAS IN ILL HEALTH, ROLLED OUT OF ITHACA in two freshly polished black trucks on February 13, 1935. The smaller truck was stuffed with machines for recording sound. The bigger vehicle contained camping gear and photographic equipment, food, tents, and other supplies. Folded down into a wooden box on top of the bigger truck was an observation platform that could be cranked up like a giant jack-in-the-box to raise a photographer to bird's-nest level, twenty-four feet above the ground.

HE CORNELL TEAM, MINUS BRAND, WHO WAS IN ILL HEALTH, ROLLED OUT OF ITHACA in two freshly polished black trucks on February 13, 1935. The smaller truck was stuffed with machines for recording sound. The bigger vehicle contained camping gear and photographic equipment, food, tents, and other supplies. Folded down into a wooden box on top of the bigger truck was an observation platform that could be cranked up like a giant jack-in-the-box to raise a photographer to bird's-nest level, twenty-four feet above the ground.

The team drove to Florida, where it searched without luck for Ivory-bills. But the members didn't waste their time. Each morning they practiced recording, faithfully rising before dawn so that Florida's milk trucks and tractors, roosters and barking dogs wouldn't drown out the birds. They worked out a routine: after arriving at a field or swamp, Paul Kellogg would drag a stool around in front of the sound truck, clamp earphones to his head, and begin twisting the dials that adjusted sound levels. Meanwhile, Jim Tanner would hoist the sound mirror in front of him like a jouster with his shield and advance steadily on the birds, dragging his boots slowly through the prickly brown Florida scrubland. As Tanner approached with the great gleaming

disk, the birds would turn to face him, puffing up their feathers and singing loud songs of warning, all of which would be recorded by Kellogg at the sound truck.

disk, the birds would turn to face him, puffing up their feathers and singing loud songs of warning, all of which would be recorded by Kellogg at the sound truck.

In April, after a month in Florida and Georgia, the trucks passed over the wide, brown Mississippi River at Natchez, Mississippi, and pulled into Tallulah, Louisiana, a flat, dusty crossroads whose office buildings and houses were bunched around a town square with a courthouse in the middle. The team drove the trucks a few blocks past the square and got out in front of the law office of Mason D. Spencer, the man who had found and shot an Ivory-billed Woodpecker just three years earlier.

Spencer was a heavyset, red-faced politician who dressed in a white linen suit and wore a straw hat. He rolled his own cigarettes, exhaling clouds of blue smoke that clung to the ceiling of his cluttered office. After introductions, Spencer gathered the Cornell scholars around a table and unrolled a map. Pointing to the spot where he had shot the bird, he repeated the epic tale of his famous discovery. It all started during a meeting of Louisiana wildlife officials in New Orleans, when someone passed on a rumor that an Ivory-billed Woodpecker had been seen in the Singer Refuge near Tallulah, along the Tensas River. After the laughter died down, someone else cracked that the local moonshine must be pretty good up there if anyone believed that.

But Mason Spencer wasn't laughing. He had a hunting camp on the Tensas, and everyone knew it. They were goading him, waiting to see how he would react. “I've seen them myself,” he declared. The others challenged Spencer to prove it by shooting one and bringing it back to New Orleans. Spencer said he'd be delighted to, if they'd write him out a state permit. Spencer got his permit, shot his bird, and, in April of 1932, went back to New Orleans and tossed a freshly killed male Ivory-bill on a conservation official's desk.

After a respectful silence, Professor George Sutton worked up the nerve to say what was on the minds of Tanner, Allen, and Kellogg as well. Clearing his throat, he said, “Mr. Spencer, you're sure the bird you're telling us about isn't the big

Pileated

Woodpecker?” The room fell silent as Spencer glared at Sutton. “Man alive!” he snorted. “These birds I'm tellin' you all about is

kints!

⦠I've known kints all my life. My pappy showed 'em to me when I was just a kid. I see âem every fall when I go deer huntin' ⦠They're

big

birds, I tell you, big and black-and-white; and they fly through the woods like Pintail Ducks!”

Pileated

Woodpecker?” The room fell silent as Spencer glared at Sutton. “Man alive!” he snorted. “These birds I'm tellin' you all about is

kints!

⦠I've known kints all my life. My pappy showed 'em to me when I was just a kid. I see âem every fall when I go deer huntin' ⦠They're

big

birds, I tell you, big and black-and-white; and they fly through the woods like Pintail Ducks!”

That was good enough for the Cornell team, especially the part about the Pintail Ducks. That was exactly how Ivory-bills flew, and only someone who had seen them could know it. Spencer sketched out a map to a guide's cabin in the swamp, and the team got hack in the trucks. Before long they were splashing through a flooded land, craning their heads out the windows to gawk up at giant trees that rose like cathedral walls from both sides of the road.

After a few miles they were waved to a halt by a man driving an empty farm wagon behind a team of mules. He introduced himself simply as Ike, and said he'd been sent to help them. They gladly pulled the trucks to the roadside, transferred their gear into his wagon, and climbed aboard. The mules plunged into the trees, following a watery trail for five miles to the cabin of J. J. Kuhn, a local warden who had agreed to help them search for Ivory-bills. It was too late in the day to start out, so they unrolled their sleeping bags on his big screened-in porch and stacked their gear in the kitchen. They were glad to hear Ike's son, Albert, already chopping wood for the fire that would cook their dinner.

Ike's wagon makes its way into the vast swamp

“DID YOU SEE IT?”

The next morning, Doc, Tanner, and Sutton filed out behind Kuhn into the great swamp forest. Kellogg stayed behind to work on the sound truck. A rainy March had turned the woods into an enormous puddle, and now only the highest ground was above water. Kuhn led the way with a long, swinging stride. Even in the muggy heat he wore a long-sleeved flannel shirt buttoned to the neck and a hunter's cap to protect his head. He rarely spoke. The always chatty Professor Sutton splashed behind in a crisply pressed shirt and a well-knotted tie. Young Tanner also dressed neatly and usually kept his thoughts to himself. Doc, always rumpled, brought up the rear.

Soon all the men's trousersâboth rumpled and crisply pressedâwere plastered to their legs. But, although soggy and uncomfortable, the men were enchanted by the vine-tangled wilderness they were passing through. The forest was fragrant with blossoms and spring warblers were singing. Best of all, it was still two weeks before mosquito season. They slipped along a narrow trail, then waded into a wide lake that Kuhn called John's Bayou. Finally, Kuhn stopped before a towering oak whose bark appeared to have been peeled like a giant carrot. Long strips of dead wood dangled in loose sheets from the trunk; they must have been pried back by something very powerful. Everyone looked around for suspects, but there were none in sight.

For two more days the men sloshed through the bayous. The forest was alive with hammering woodpeckers, but they heard no Ivory-bills, not even a call or a rap. By the third day Kuhn had grown anxious. He kept insisting that the birds were there, that he had seen them himself just weeks before. Finally, he decided the only choice

was to head into deeper water. The team doubled back through John's Bayou and, soaked to the skin now, turned due east, wading into what Sutton described as “a twilight of gigantic trees, poison ivy, and invisible pools.”

was to head into deeper water. The team doubled back through John's Bayou and, soaked to the skin now, turned due east, wading into what Sutton described as “a twilight of gigantic trees, poison ivy, and invisible pools.”

The four explorers spread out and advanced in a straight line like beaters on an African safari, shouting frequently since they couldn't see each other. After they had gone a few hundred yards, Sutton thought he heard Kuhn yelling excitedly, but he couldn't make out what he was saying. Sutton took off in pursuit, calling back over his shoulder for Tanner to follow, and Tanner began sprinting as he shouted back to Allen. When they all caught up with Kuhn, his face was red with excitement. “Right

there,

men,” he said as he jabbed his finger into the forest. “Didn't any of you

hear

it?” They cupped their hands to their ears. All they could hear was Pileated Woodpeckers.

there,

men,” he said as he jabbed his finger into the forest. “Didn't any of you

hear

it?” They cupped their hands to their ears. All they could hear was Pileated Woodpeckers.

So they advanced again, this time more slowly and closer together. Kuhn and Sutton were the first to hop onto a huge cypress log, teetering along it with their arms out so they could see and hear more clearly. Suddenly Kuhn stopped and whispered, “There it goes, Doc! Did you see it?” He grabbed Sutton's shoulder and whirled him around, nearly sending them both toppling off the log. Kuhn was shouting now. “A nest! See it! There it is, right up there!” Sutton was uncertain. He

had

seen something, an arrow-like shadow of some kind, fly to a dead tree, but he wasn't sure what it was. Gradually his eyes began to focus on a big oval hole high up in that same tree.

had

seen something, an arrow-like shadow of some kind, fly to a dead tree, but he wasn't sure what it was. Gradually his eyes began to focus on a big oval hole high up in that same tree.

Kuhn, overjoyed, grabbed the distinguished Ivy League professor and led him in a jig as Tanner arrived in a rush, nearly knocking them both off the log. Then Doc Allen entered the picture, crashing through the woods like a bear. The four of them, laughing, danced on the log, mostly to honor Kuhn, since they still hadn't seen what he had. And then, as they were dancing, a bird began to call. They froze in place. “The cry was strange, bleatlike,” Sutton wrote. “The moment I heard the sound I knew I had never heard it before.”

At that moment a large black-and-white spear went streaking toward the tree. Crouching low, Tanner and Sutton finally got their first look at the legendary bird, and Allen beheld an old friend again at last. A female Ivory-bill flew into the nest, poked her head out, and flew away again. “Much white showed in her wings,” Sutton remembered. “Her long black crest curled jauntily upward at the tip. Her eyes were white and fiercely bright. Her flight was swift and direct.”

An Ivory-bill, like the one seen by Allen, Sutton, and Tanner, flies away from its nest

Then she returned with her mate. The male was a little bigger, with a backward-sweeping red crest instead of a forward black one. The male caught sight of the men and turned his head to look at them directly. He flew to a limb overhead and looked down with head cocked, through first one brilliant amber eye and then the other. “What a splendid creature he was!” wrote Sutton. “He called loudly, preened himself, shook out his plumage, rapped defiantly, then hitched down the trunk to look at me more closely. As I beheld his scarlet crest and white shoulder straps I felt that I had never seen a more strikingly handsome bird.”

So there it was. After years of rumors, dead ends, and false alarms, Doc had his second chance and the Cornell team had its star bird for the sound project. Not just a single bird, either, but a mated pair with a nest. That night, back at Kuhn's cabin, they turned their attention to the next task. They had found the Ivory-bill; now the job was to record its voice. But how in the world would they ever haul 1,500 pounds of America's most sensitive sound equipment into the spongy middle of nowhere?

THE NIGHTMARE SWAMP

The wilderness in which the Cornell team now found themselves was a patch of the Mississippi River's delta, a vast area formed when the great river, swollen from melting snow and rains from as far north as Minnesota, flooded its hanks each spring, carrying with it a load of riverbottom soil known as silt. Thousands of years of floods had spread the silt like a rich layer of brown frosting over an area five hundred miles long and fifty miles wide. Mississippi delta silt was some of the best soil in the world for growing trees. The bottomland forest, as it was called, was prime Ivory-bill country.

Most of the delta had been cleared and settled, but there was one great wilderness forest southwest of Tallulah still standing. The Tensas River, an old, slow-moving channel of the Mississippi, snaked lazily back and forth through its trees as it had long before human memory. In the 1830s a few pioneers had arrived to clear away trees and plant cotton along the river's banks. After a levee was built to hold the Mississippi's spring floods, more families came, building grand white-columned houses. Set apart from the big houses were clusters of crude shacks, quarters for Negro slaves who soon outnumbered whites nine to one along the river.

Behind the buildings were fields of cotton which, after the cotton bolls burst open, shone bleached white in the blazing sun. And just behind the cotton fields, always in sight, loomed the imposing trees of the nightmarish Tensas swamp. People believed that everything that crawled, howled, lurked, snapped, hooted, screamed, and slithered lived right back there, just beyond the fields. And they were right. After visiting the swamp in 1907, Theodore Roosevelt wrote, “We saw alligators and garfish; and monstrous snapping turtles, fearsome brutes as heavy as a man with huge horny beaks that with a single snap could take off a man's hand or foot ⦠Thick-bodied water moccasins, foul and dangerous, kept near the water, and farther back in the swamp we found and killed rattlesnakes and copperheads.”

THE TAENSA

The Tensas swamp is laced with huge mounds that, from the air, look like welts in the muddy earth. They are burial mounds of the Taensa Indians, the group that occupied the area before whites appeared. When the French explorer Sieur René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle traveled down the Mississippi to explore the delta in 1682, he visited a Taensa village and was welcomed warmly. The French described the Taensa as a people who lived in large, well-made buildings. They worshipped the sun and kept a fire burning all the time in a temple that had a roof decorated with the carved likenesses of three birds. When a chief died, they sacrificed a number of his friends and relatives so that they could accompany him into the afterlife. Later, most of the Taensa Indian population was killed by smallpox and measles viruses carried by whites, against which the Indians had no defenses.

In 1861 the Civil War broke out, and the following year Yankee troops seized control of much of the Mississippi River. Yankee soldiers descended upon the Tensas plantations, stealing horses, cattle, and food, freeing slaves, and terrorizing those remaining in the plantation homes, most of whom were women and children.

Planter families faced a desperate choice: they could either stay at home and wait for the Yankees or flee to Texas through the dreaded swamp. Many said their prayers, set fire to their cotton crops, and plunged on foot and horseback into the dark trees.

Seventy years later, in 1935, when the Cornell ornithologists hunted for Ivory-billed Woodpeckers in this same swamp, there was little evidence of the cotton society or the Civil War. The ruins of a few plantation buildings lay smothered beneath fragrant flowering vines. Trees had sprouted back so quickly along the Tensas that they soon blended in with the giants behind them. It was as if no one had ever lived there.

But the rest of the vast Mississippi delta had changed plenty. Railroads finally reached the Tensas River sometime around 1900, ushering in lumber crews and logging equipment. For about thirty years loggers had been steadily closing in on the Tensas swamp from the north and the south, like a giant set of alligator jaws. Soon it was the last big scrap left of the Mississippi River bottomland forest, once a green carpet that had stretched from Memphis, Tennessee, to the Gulf of Mexico.

TR, BEARS, AND IVORY-BILLS

In the fall of 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt set out to kill a bear “after the fashion of the old Southern planters.” That meant tracking it on horseback and using dogs to sniff it out. TR's huge hunting party chose the Tensas River swamp, notoriously thick with bears.

The President thought he had seen big trees before, but he nearly got a cramp in his neck gawking up at the skyscrapers growing from the bottom of the swamp. “In stature, in towering majesty, they are unsurpassed by any trees of our eastern forests; lordlier kings of the green-leaved world are not to be found until we reach the sequoias and redwoods of the Sierras.”

The wild creatures were just as amazing. TR saw minks, raccoons, possums, deer, black squirrels, wood rats, panther tracks, and, of course, bears, one of which he killed. But one creature impressed him above all. “The most notable birds and those which most interested me were the great Ivory-billed woodpeckers. Of these I saw three, all of them in groves of giant cypress; their brilliant white bills contrasted finely with the black of their general plumage. They were noisy but wary, and they seemed to me to set off the wildness of the swamp as much as any of the beasts of the

chase.”

chase.”

The giant oaks and ashes and sweet gums along the Tensas seemed doomed, too, until, one day in 1913, the dry scratch of a pen against paper in New York City froze the powerful jaws of development in midbite. On March 28 of that year, Douglas Alexander, a portly white-haired man in a business suit, stood beside his elegant wife, Helen, in a New York City courthouse and looked on as she signed her name to a deed that gave the Ivory-bill one last chance. She signed it not to help woodpeckers, but so that her husband's company could sell sewing machines.

For Douglas Alexander was president of the Singer Manufacturing Company, and Singer needed oak trees. Many Singer machines folded down into cabinets, becoming flat-topped tables when no one was sewing. Women around the world loved the oak cabinets because they were beautiful, and because they saved space in cramped tenements and crowded rooms. But America was running out of oak trees.

For Douglas Alexander was president of the Singer Manufacturing Company, and Singer needed oak trees. Many Singer machines folded down into cabinets, becoming flat-topped tables when no one was sewing. Women around the world loved the oak cabinets because they were beautiful, and because they saved space in cramped tenements and crowded rooms. But America was running out of oak trees.

THE BIG REDS

In 1913, the year that the Singer Manufacturing Company bought a big chunk of the Tensas swamp, the company sold 2.5 million machines around the world to countries as far-flung as Spain, Russia, or Japan. Singer's headquarters, the Singer Building, was the tallest building in the world, rising forty-seven stories above Broadway in New York City. As president of the Singer company, Douglas Alexander commanded one of the biggest business empires in the world. He was fabulously rich, and so admired that in a few years he would even be knighted.

Alexander's scouts had found one last forest of uncut hardwoods. It was for sale in the Mississippi delta, in northeastern Louisiana. Singer bought the Tensas swamp for about nineteen dollars an acre and immediately declared its new property a “refuge,” meaning that the trees were not to be cut without the Singer company's approval. Hunting was forbidden. The forest began to appear on Louisiana maps as the Singer Refuge and was later called by conservationists the Singer Tract.

But Singer soon found that it was much easier to get the word “refuge” put on a map than to keep hunters out of a game paradise. Families had been shooting their food in these woods for years, and powerful politicians like Mason Spencer often retreated to hunting cabins along the Tensas River where damp bottomlands teemed with bear, deer, and turkey. No one was going to quit hunting on account of a sewing-machine company.

Finally, in 1920, the Singer company offered Louisiana's Fish and Game Department the chance to manage Singer's land as long as the state agreed to hire wardens to regulate hunters and tree poachers. J. J. Kuhn was employed as a Singer warden when Tanner, Allen, Kellogg, and Sutton showed up in Tallulah. At first he had seen his job simply as keeping hunters out. But for the past three years, ever since Mason Spencer had shot the big woodpecker, he had found himself guiding scientists through the forest looking for Ivory-bills. His curiosity about the great birds had grown by leaps and bounds, to the point where he not only knew where the birds were, but knew the entire forest by heart. What had seemed simply a game forest was now something more. Kuhn had come to realize that his place of work was a sort of forested oasis, an intact natural island surrounded by a rising tide of lawns, paved roads, and cotton fields.

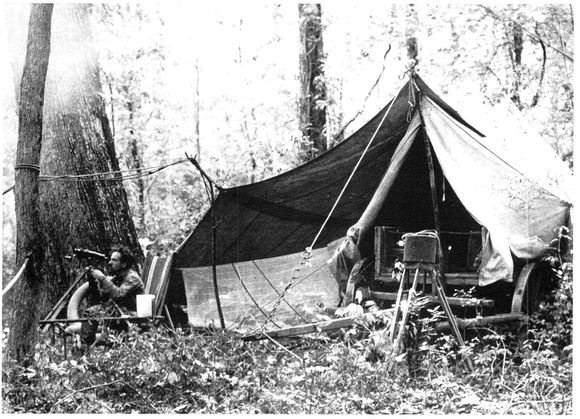

Paul Kellogg squints at Ivory-bills through a spotting scope while Jim Tanner listens to their sounds through recording equipment sheltered beneath the tent

Other books

Darcy & Elizabeth: A Season of Courtship (Darcy Saga Prequel Duo) by Sharon Lathan

Captive at Christmas by Danielle Taylor

Love is Blindness by Sean Michael

Deep Blue Sea by Tasmina Perry

Fem Dom by Tony Cane-Honeysett

Crooked by Laura McNeal

Hotlanta by Mitzi Miller

The Life and Loves of Gringo Greene by Carter, David

Drake the Dandy by Katy Newton Naas

Cobalt by Aldyne, Nathan