The Price of Civilization: Reawakening American Virtue and Prosperity (8 page)

Read The Price of Civilization: Reawakening American Virtue and Prosperity Online

Authors: Jeffrey D. Sachs

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Economic Conditions, #History, #United States, #21st Century, #Social Science, #Poverty & Homelessness

The apogee of government leadership of the economy was reached in the mid-1960s, immediately following John F. Kennedy’s assassination. Lyndon B. Johnson declared war on poverty in early 1964 and launched an astonishing array of legislative initiatives in 1965, including: the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, the Water Quality Act of 1965, the Higher Education Act of 1965, the Federal Cigarette Labeling and

Advertising Act of 1965, the Solid Waste Disposal Act of 1965, the Motor Vehicle Air Pollution Control Act of 1965, and, most important in terms of size of outlays, the Social Security Amendments of 1965, which ushered in Medicare for the elderly and Medicaid for the indigent. The War on Poverty had its most lasting effect on two groups, the elderly and African Americans. Medicare and the expansion of Social Security effectively ended the persistent high poverty among those over sixty-five. In 1959, the elderly poverty rate stood at 35.2 percent; it fell to 25.3 percent by 1969 and just 9.7 percent by 2007. African American poverty rates fell from 55.1 percent in 1959 to 32.2 percent in 1969 and 24.5 percent in 2007.

8

One more crucial factor made possible the surge in social programs during the period of the 1960s: the availability of

existing

government revenues to pay for them. Up until the mid-1960s, politicians could enact new social programs without having to raise taxes as a share of national income for a simple but powerful reason: the federal tax system that emerged from World War II and the Korean War (1950–1953) was able to collect 18 percent to 19 percent of GDP in revenues and therefore to support a roughly equivalent level of spending; as defense spending declined after the Korean War, nondefense spending had room to expand.

9

The Great Reversal

As of the mid-1960s, most political observers expected a continued ascendancy of social programs in the service of promoting prosperity and fighting poverty. Few guessed at the time that the great consensus on the role of government in the economy would soon begin to unravel, and that a rival economic strategy calling for small government and privatization of public functions would surge to the forefront by 1980. Deep social cleavages surrounding the civil rights movement were the first wedge in the national consensus. I describe

those in the next chapter. Yet economic shocks also played a role in undermining the public’s confidence in Washington.

The rise of inflation at the end of the 1960s and a series of major economic upheavals of the 1970s shook the faith of the public in the ability of government to steer the economy and to fight poverty at a modest cost to society. The two most important events were the collapse of the post—World War II global exchange-rate system in 1971 and the sharp increases in oil prices in 1973–1974 and again in 1979–1980.

10

Rather than see the events of the 1970s as temporary aberrations requiring specific problem solving, conservative politicians, with Reagan as spokesperson, argued that they were signs of fundamental failures of the public sector and its role in the economy.

President Jimmy Carter’s one term, 1977–1981, proved to be the transition in every way.

11

Big Labor lost its political influence reflecting the rise of Sunbelt power and that region’s antipathy to organized labor.

12

The 1978 Revenue Act began the process of cutting capital gains taxation that would be greatly extended during the Reagan years. The tax measure “discarded historic principles of interclass equity and methods of promoting business investment” and was “not simply a triumph of capital, but of financial capital, which was assuming a prominent role in U.S. politics.”

13

Japan’s exports to the United States in steel, automobiles, and electronics goods surged, giving the United States a first taste of the tough competition that would arise in the new era of globalization.

Carter also began the processes of deregulation (notably in airlines, trucking, and finance) that would become a hallmark of the Reagan years and after. Many of Carter’s forays into deregulation (for example, in transport) proved to be successful, but the process of deregulation got out of hand in the years that followed, especially in the financial sector. And tellingly, Carter lost his effort to reform the energy sector, tripped up by the power of the oil and gas sector to block his initiatives in alternative energy sources. By 1981, the country was set for a major transformation favoring the Sunbelt, financial capital, wealthy Americans, and Big Oil.

All of this tumult gave an extraordinary opening to the new philosophical assertion that it was “big government” itself rather than new and specific challenges (energy, the exchange rate, and so forth) that constituted the major barrier to prosperity. This was an odd assertion. The major problems that had been experienced were macroeconomic in nature: the collapse of the gold-based exchange system, the budget deficits caused by the Vietnam War, and the oil price shocks. They did not, evidently, relate to the size of government (other than the Vietnam War) as much as to shifts in the world economy.

The assertion that big government had destabilized the economy was doubtful on its face, but Reagan uttered his ideas with such conviction and charm that an unhappy public was ready to vote him into office. Had the evidence been brought to bear, the flimsiness of the claim would have been exposed. Federal tax revenues as a share of GDP were nearly constant from the mid-1950s onward at 17 percent to 18 percent of GDP. Total federal spending as a share of GDP had increased slightly, from around 18 percent of GDP in the late 1950s to around 20 percent of GDP in the late 1960s and 21 percent of GDP in the late 1970s.

There was no evidence then—or now, looking back—that the shocks of the 1970s had much if anything to do with the War on Poverty, social programs, infrastructure investment, science and technology, community development, Medicare, Social Security, or other government programs. Yet the chaos created by the oil price shocks, the new floating exchange rate regime, and lax monetary policies by the Federal Reserve reverberated into budget politics. Suddenly tax cutting, shrinking civilian government, and rolling back welfare policies became the vogue and the diagnostic basis for policy change. There was no turning back. However dubious was the interpretation of the economic mayhem of the 1970s, a political reality had resulted: government lost its aura of competency. Probably this alone was fatal to the economic consensus that had guided the country for almost forty years.

The Reagan Revolution

The political coalition that put Reagan into office was determined to create a lasting legacy of a smaller federal government (“to curb the size and influence of the federal establishment”), and in this it partly succeeded. There were four main instruments of the Reagan Revolution: tax cuts on higher incomes, restraints on federal spending on civilian programs (at least relative to the growing economy), deregulation of key industries, and outsourcing of core government services. All four of these major policy changes took hold in the 1980s and are still in place today.

At the aggregate level, the Reagan Revolution did not shrink the federal public administration, but it probably did stop it from expanding. The federal civilian bureaucracy had 2,109,000 full-time-equivalent civilian employees in 1981, the same in 1988, and nearly the same over the next twenty years, with an expected 2,101,000 full-time-equivalent civilian employees in 2011.

14

In terms of taxation, total federal revenues as a share of national income in 2007, before the financial panic, stood at 18.5 percent, virtually unchanged from the start of the Reagan administration. Total spending in 2007 stood at 19.6 percent of GDP, slightly lower than the 21.7 percent of GDP in 1980. Civilian spending was 13.9 percent of GDP in 2007, down slightly from 14.8 percent of GDP in 1980.

The larger shift from Reagan onward was across the categories of domestic spending.

15

As we saw in

Figure 4.2

, discretionary civilian spending declined from 5.2 percent of GDP in 1980 to around 3.6 percent of GDP in 2007 (before a temporary recession-related boost). Mandatory spending, mainly transfer programs to individuals such as Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security, and veterans’ benefits, grew slightly, from 9.6 percent of GDP in 1980 to around 10.4 percent of GDP in 2007. Thus the Reagan Revolution set into motion a squeeze on government investments in areas such as education, infrastructure, energy, science and technology, and other

productivity-enhancing areas, while leaving mostly untouched the growth of transfers to individuals for health care and retirement.

Demonizing Taxation

The deepest political impact of the Reagan era was the demonization of taxes. Taxes are rarely popular, especially in the United States, a country that was founded on a tax revolt. Taxes not only take money out of pockets; they are widely seen by Americans as a denial of freedom itself. The standard libertarian line is that since government collects around a third of national income, it’s as if Americans are indentured to the government, even its slaves, during January through April of each year. Accurate or not, the anti-tax sentiment is ingrained in the American political discourse.

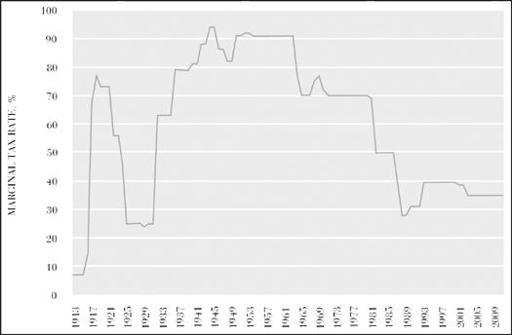

Reagan’s main target was to reduce the top marginal tax rates on rich taxpayers. The history of the top marginal tax rates is shown in

Figure 4.3

. The federal income tax is a recent invention, just one century old. At the start, the highest marginal tax rate was a very modest 7 percent, but within a few years, and due to America’s entry into World War I, the top marginal tax rate soared to 77 percent in 1918. In the 1920s, the conservative administrations of Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover brought the top rate back down to 25 percent, where it stood at the time of the Black Tuesday stock market crash on October 29, 1929, that marked the onset of the Great Depression.

Figure 4.3: The Top Marginal Personal Income Tax Rate, 1913–2009

Source: Data from Tax Policy Center (Urban Institute and Brookings Institution).

With the New Deal, the top marginal tax rate rose to 63 percent, and then it rose further during World War II, to reach 94 percent by 1945. It remained near this stratospheric level until the 1960s, when tax cuts during the Johnson administration reduced it to 70 percent in 1965. It remained around that level until the Reagan Revolution. A series of tax cuts at the center of the Reagan agenda reduced it in steps to 28 percent by 1988. It is a mark of the lasting legacy of Reagan that the top marginal tax rate has not again reached even 40 percent since then. Obama entered office with the top rate at 35 percent.

Reagan argued for tax cuts on three major grounds: that lower marginal tax rates would improve the incentives for innovation and entrepreneurship; that the increased growth following the tax cuts would mean higher rather than lower government revenues; and that lower tax rates would lead the way to a smaller government overall, on both the tax and spending sides. The message was contradictory. Would tax revenues go up or down? Would spending, even on popular programs, have to be cut? Reagan’s team had it both ways: that tax cuts would be self-financing through faster growth and that they would be the leading edge into politically difficult spending cuts. We’ll continue to return to the implications of the tax cuts in later chapters. Suffice it here to state that the tax cuts were not self-financing. They led to large budget deficits and to pressures to cut government spending on domestic discretionary programs, all the more because spending on the military rose.

Cutting Civilian Outlays

It was also an overt goal of Reagan and his supporters, almost as important as the tax cuts, to cut the size of civilian government outlays while simultaneously boosting military spending. Civilian programs were viewed as wasteful, unnecessary, and lavish transfers to the undeserving poor. One of Reagan’s lasting images was the “welfare queen,” a larger-than-life individual, always imagined as an African American woman, who bilked the federal welfare programs by registering for benefits under multiple aliases. Whether such a figure truly existed was much debated, but the wildly popular idea that welfare fraud was rampant led to a surge of public support for cutting or eliminating many income support programs. The War on Poverty thus became a war on the poor.

The broadest indicator of the post-1980 change is the share of national income devoted to the provision of public goods and services in several categories.

Figure 4.1

showed the overall civilian budget of the federal government relative to GDP. We can see that the Reagan Revolution achieved one of the first things it set out to accomplish: an end to the rising trend of civilian outlays as a share of GDP. The civilian budget rose from around 5 percent in 1955 to a peak of 14.9 percent of GDP in 1981. Then the increases stopped. Total civilian spending remained in the range of 13 to 15 percent of GDP thereafter, settling at 13.9 percent of GDP in 2007, the year before the financial crash and the rise in stimulus spending.