The Price of Civilization: Reawakening American Virtue and Prosperity (28 page)

Read The Price of Civilization: Reawakening American Virtue and Prosperity Online

Authors: Jeffrey D. Sachs

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Economic Conditions, #History, #United States, #21st Century, #Social Science, #Poverty & Homelessness

Our Ultimate Economic Goals

It is easy to lose sight of the ultimate purpose of economic policy: the life satisfaction of the population. That ultimate goal should be unassailable for a country founded precisely to defend the inalienable right to the pursuit of happiness. Yet not only do we miss myriad opportunities to promote happiness through our collective undertakings, we even miss the opportunities to measure happiness so that we can gauge how we are doing as a nation. Our fixation on GDP/GNP crowds out our attention to more important indicators. As Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., put it:

For too long we seem to have surrendered personal excellence and community value in the mere accumulation of material things. Our gross national product now is over 800 billion dollars a year, but that gross national product, if we judge the United States of America by that, that gross national product counts air pollution, and cigarette advertising, and ambulances to clear our highways of carnage. It counts special locks for our doors and the jails for people who break them. It counts the destruction of the redwoods and the loss of our natural wonder in chaotic squall. It counts Napalm, and it counts nuclear warheads, and armored cars for the police to fight the riots in our city. It counts Whitman’s rifles and Speck’s knifes and the television programs which glorify violence in order to sell toys to our children. Yet, the gross national product does not allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education, or the joy of their play; it does not include the beauty of our poetry or the strength of our marriages, the intelligence of our public

debate or the integrity of our public officials. It measures neither our wit nor our courage, neither our wisdom nor our learning, neither our compassion nor our devotion to our country; it measures everything in short except that which makes life worthwhile. And it can tell us everything about America except why we are proud that we are Americans.

24

There have been growing efforts to expand the range of indicators to measure better what’s important for our well-being. The World Values Survey and Gallup International have each pioneered various measures of subjective well-being, which psychologists and economists have found to be stable, slowly evolving, and useful for social diagnostics. The Human Development Index (HDI) is another well-known attempt to combine economic indicators with social indicators (literacy, school enrollment, and life expectancy) to give a more rounded picture of well-being. The American Human Development Project has recently extended the HDI to American states, counties, and congressional districts, an enormously helpful contribution to assessing the diversity of America’s economic and social conditions.

25

No country has taken the challenge of measuring, and raising, happiness more seriously than the Himalayan Buddhist Kingdom of Bhutan. Back in 1972, the country’s fourth monarch, Jigme Dorji Wangchuk, called for the country to orient its policies to promote the gross national happiness rather than the gross national product. This challenge has not been taken lightly or figuratively. The government of Bhutan established the Gross National Happiness Commission to oversee a series of metrics that would quantify and track the changes in national happiness.

26

GNH is measured in nine domains:

- Psychological well-being

- Time use

- Community vitality

- Culture

- Health

- Education

- Environmental diversity

- Living standard

- Governance

Each of these is measured by a series of quantitative indicators. What is notable is the combination of relatively standard economic measurements such as household income and education with measures of cultural integrity (e.g., the use of dialects, engagement in traditional sports and community festivals), ecology (e.g., forest cover), health status (e.g., body mass index, number of healthy days per month), community well-being (e.g., social trust, kinship density), time allocation, and general mental health (e.g., indicators of psychological distress).

The worldwide movement to measure happiness and the quality of life is now expanding very rapidly. The OECD launched a Global Project on Measuring the Progress of Societies in 2004, and the European Commission is moving forward on its own set of integrated indicators. There have been countless recent attempts to correct GNP to account for its many anomalies (subtracting various “bads” such as pollution, congestion, and resource depletion from the standard GNP accounts), starting with the Measure of Economic Welfare (MEW) pioneered by William Nordhaus and James Tobin. The Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI) is a similar initiative to correct GNP for several factors such as inequality, congestion, and pollution. In 2005, the

Economist

Intelligence Unit demonstrated that “quality-of-life” across countries is reasonably well explained statistically by a combination of measurable economic, political, health, job security, and community indicators. Many scholars have confirmed similar results in recent academic studies.

27

Recently the French government convened a commission headed by Joseph Stiglitz and Amartya Sen to propose a new set of indicators, and in 2010 the U.K. government announced that it would directly monitor subjective well-being in annual surveys.

28

It is time for the United States to take seriously the measurement and monitoring over time of Americans’ well-being. Two key facts—that self-reported happiness has been stuck or even declining as income has grown and that the United States is falling behind many other countries in happiness and its underlying determinants—make this new effort especially urgent.

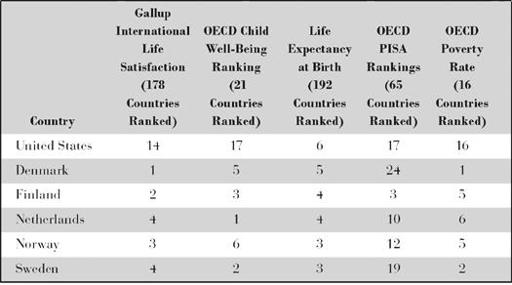

Table 10.2

illustrates the kind of well-being measures that would be collected each year in addition to the standard national income accounts. Gallup International, for example, uses opinion surveys to assess the average “life satisfaction” in 178 countries by asking “All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole these days?” The OECD has created an index of child well-being that aggregates over six dimensions: material conditions, housing, education, health, risk behaviors, and quality of school life. Other indicators might include variables such as life expectancy, student test scores, and the poverty rate, all shown in the table. Clearly, the United States has its work cut out for it to raise its standard of average well-being compared with what other high-income countries are achieving.

Table 10.2: Indicators of National Well-Being (Rankings, with 1 = “Best”)

Source: Gallup, OECD Statistical Databases, World Health Organization.

CHAPTER 11.

Paying for Civilization

In fiscal year 2011, the federal government covered around 39 percent of its spending, roughly $1.4 trillion of $3.6 trillion, by borrowing.

1

Each year’s borrowing adds to the total public debt. In 2007, the government debt held by the public amounted to around 36 percent of GDP.

2

By 2015 the debt is expected to soar to 75 percent of GDP.

3

Some economists try to tell us not to worry as we rack up the debt. They pitch tax cuts today as a demand stimulus (according to the Democrats) or a supply stimulus (according to the Republicans), without telling us about the long-term costs. I have my serious doubts about such shortsighted arguments.

As the debt rises, the burden of paying the interest on it will rise as well. Today we spend around 1.5 percent of GDP to pay the interest.

4

By 2015, it could be around 3.5 percent of GDP. By 2020, it could reach 4 percent of GDP or more. This interest servicing will crowd out other vital spending, for example for infrastructure or help for the poor. Or it will require a hugely contentious tax increase, with revenues that instead should have been used for essential public goods. Or it will cause a future financial crisis as global lenders lose confidence in the capacity and willingness of the

U.S. government to honor its debts other than by inflation (printing money to pay them off). It’s better, therefore, to try to stabilize the debt relative to GDP and then begin a process of gradual reduction in the debt-to-GDP ratio.

This chapter, then, is about our government paying its bills on time through adequate tax collections, rather than borrowing from the future. As the great Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., wrote, “I like to pay taxes. With them I buy civilization.”

5

It is a sentiment utterly unrecognizable in America today, where an ongoing thirty-year tax revolt predominates. Without adequate taxation, we can’t live in a civilized country. Middle-class Americans are so sure that higher take-home pay is the key to their happiness that they’ve lost track of the need to pay taxes to fund society-wide undertakings and avoid an explosion of public debt. More important, middle-class Americans have repeatedly given the green light to tax cuts for the richest Americans, allowing income and wealth to concentrate among a tiny fraction of the population. The richest then invest a very small fraction of their wealth to dominate the airwaves, enrich members of Congress and their families, and preserve their privileges. Congress needs little cajoling by lobbyists; it has itself become a millionaire’s club, with 261 members, almost half, of today’s Congress holding at least $1 million in assets.

6

Getting the rich to accede to Justice Holmes’s wisdom is a big part of the challenge. Getting the government to plan and implement long-term policies properly and competently is another. The two changes are, of course, inseparable. There is no way to increase the scale of government if the government remains as incompetent and corrupt as it is today. This chapter takes up the challenge of how to pay for a government that does its proper job. The next chapter takes up political reform, how to take government back from the corporatocracy and put it back into the service of public well-being.

The Basic Fiscal Arithmetic

America’s peacetime budget deficit is unprecedented: $1.3 trillion in 2010, equal to 9 percent of the national income. And the deficit could well remain above $1 trillion for years to come. The problem with economic reform in America is how to pay for public goods: quality education, college completion, advanced energy technologies, improved roads, safe child care, and decent health care. The quality of life is deteriorating because we refuse to pay for the public goods needed for a civilized society.

The Tea Party’s answer is to leave the needed investments to the private market. This, as we’ve seen in earlier chapters, will not do. We are required, in one way or another, to address the budget deficit and at the same time address the challenges that we’ve inherited from these market failures and the powerful forces of global capitalism.

The lack of budget resources is now the fundamental constraint on effective governance and a sustainable recovery. It’s fair to say that all our civilian programs other than the entitlements programs are paid for with borrowed money and borrowed time. The result, as we know, is political paralysis. As much as we’d like to do more and better things, we simply can’t afford them. And the squeeze on civilian discretionary programs has tightened considerably over the years, since Ronald Reagan put the country on the course of repeated tax cuts.

There is nothing more important today than understanding the basic arithmetic of the budget and of household incomes to understand the predicament.

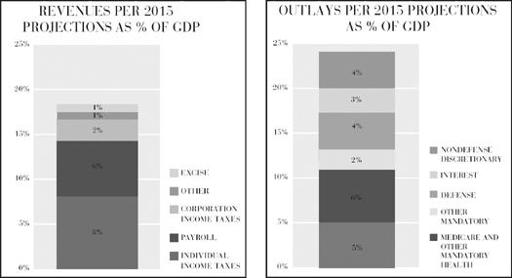

This is shown in

Figure 11.1

. Under the current tax system, the federal government will collect around 18 percent of GDP in 2015, with the breakdown shown in the chart. For this baseline calculation, I assume that the Bush-era tax cuts that were extended at the end of 2010 for two years will be extended again after 2012.

7

Figure 11.1: Revenues and Outlays as a Percentage of GDP in 2015 Budget Projections