The Price of Civilization: Reawakening American Virtue and Prosperity (20 page)

Read The Price of Civilization: Reawakening American Virtue and Prosperity Online

Authors: Jeffrey D. Sachs

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Economic Conditions, #History, #United States, #21st Century, #Social Science, #Poverty & Homelessness

Source: Data from the RTL Group and OECD.

The relentless streams of images and media messages that confront us daily are professionally designed to distort our most important decision making processes. We are encouraged to act on impulse and fantasy instead of reason. And we need to understand that the difficulty of maintaining our balance in a media-rich economy is even greater than we might have supposed even ten or fifteen years ago. The advances in modern neurobiology and psychology have revealed a level of human vulnerability that would have surprised even Freud and Bernays.

The problem is not just that we are a bundle of rational and irrational motives that operate without our conscious knowledge and therefore are vulnerable to unconscious manipulation. Uncle Freud and nephew Bernays knew that, and generations of research psychologists have since confirmed it time and again, by showing how our decisions are influenced by the slightest changes in mood, setting, or unconscious cues as manipulated by the experimenter. The newly understood fact is that we are also biological “works in progress,”

even into our later years. Our brains, and hence personalities, decision making capacities, and values, are subject to extensive and continued neural rewiring over time. We are not just what we eat. We are also what we see and hear, since these literally change our brains, minds, and future judgments.

This constant reshaping of our brains, and our deep vulnerability to manipulation, require us to understand just how strange our advertising-laden economy really is. We’ve learned more and more that human beings are vulnerable to manipulation, yet we’ve also fostered a vast advertising and PR industry designed to prey on those weaknesses. The neuroscientists give us four reasons why advertising and mass consumerism should concern us even more than we might suppose.

First, our brains are malleable. Scientists use the term “neuroplasticity” to describe the fact that our brains are continually being rewired depending on the kinds of stimuli that we receive and the ways that we choose to behave. Meditation can help us gain calm. TV watching can reduce that sense of calm, especially among young children. Second, animal behaviorists emphasize the importance of “super-normal stimuli,” meaning simple cues of color, sexual stimulation, or some other sensory information that can trigger highly complex behavior. Harvard psychologist Deirdre Barrett has convincingly extrapolated from the remarkable animal findings to argue that humans too are biologically configured to respond powerfully to particular cues.

8

The food industry entices us with the fatty foods and refined sugars that we naturally crave. Marketers easily lure us into buying cars, beer, and cigarettes through the sexually provocative poses of models selling these products. These are well-known lures, of course, but we’ve opened the floodgates through the ubiquity of advertising. Third, our vulnerability to addiction makes it easy for the marketers to hook young children into a lifetime of consumption and overconsumption. We are a society of pushers, not the drug gangs, but many of the biggest names in advertising. Fourth, many of our decisions are unconsciously made. We are often not

even aware of why we’ve made a purchase or latched on to a particular product. The brain is easily “primed” by sights, smells, and stimuli of which we are not even aware, inducing us to buy products for reasons that are even obscure to the purchaser.

When I reflected on such issues twenty or more years ago, I regarded the problems of consumer addictions and “irrationalities” to be serious social issues but not serious macroeconomic issues. Addictions were for social workers and drug enforcement officials to deal with. Macroeconomics, I reasoned, is about the preponderance of behavior, not about the oddities and painful exceptions. I no longer accept that division of labor between psychology and economics. Within one generation, Americans have displayed a shocking array of addictive behaviors (smoking, overeating, TV watching, gambling, shopping, borrowing, and much more) and loss of self-control. These unhealthy behaviors surely have reached a macroeconomic scale and raise deep questions about our well-being in an era of relentless advertising and excess. Have we actually created a world that is programmed to undermine our very balance as individuals? Our society is addicted to overconsumption and household debt. It is addicted to a miserable diet that has led to a staggering 33 percent obesity rate. It is addicted to television itself, with individuals spending four to six hours per day in front of the tube and indications that they are unhappy as a result.

The Marriage of Mass Media and Hypercommercialism

The astounding fact of America’s media system is that it has become a juggernaut out of social control, one that is partly responsible for carrying America to the abyss. The media juggernaut has taken over our living rooms, our national politics, even the battlefields. It is yet another of the runaway factors that are destabilizing American society. The media, major corporate interests, and politicians now constitute a seamless web of interconnections and power designed to

perpetuate itself through the relentless manufacture of illusion. The media peddle illusions, and those illusions lead to even more addictive behaviors, including the fixation on the media itself.

Many observers have documented how America took a distinctive course in the TV age, thereby opening itself to maximum long-term vulnerability to the dark arts of propaganda, both corporate and official. Most consequentially, at the start of the TV era the government decided to hand the TV networks almost entirely to the private sector, based on an advertising-led model of broadcasting. In 1934, Congress rejected the alternative approach of a mixed public-private system when it passed the Communications Act of 1934.

For several decades, the federal government, largely through the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), maintained at least some regulatory control on private broadcasters to enforce some public-spiritedness and competition.

9

As in so much of American society, however, the corporate-owned media escaped the grasp of public regulation during the 1980s and 1990s, so that by the beginning of the twenty-first century, the media stood unchallenged by government and indeed had become a full-fledged propaganda partner with Washington.

One key stop on the journey of the private sector’s complete takeover of the airwaves came in 1996, with the Telecommunications Act signed into law by President Clinton. Yet again, Clinton proved that corporate empowerment is bipartisan, without much difference between the Republicans and the Democrats. The new act effectively undid the remaining barriers to media concentration in TV and radio and unleashed a wave of corporate mergers, creating the mega–media companies. As of today, the media giants include Disney, Comcast, Westinghouse, Viacom, Time Warner, and News Corporation.

The media and the politicians now live in splendid symbiosis. The airwaves promote corporate products, consumer values, and the careers of friendly politicians. The politicians promote media deregulation, low taxes, and freedom from scrutiny of performance and public service.

Measuring Hypercommercialization

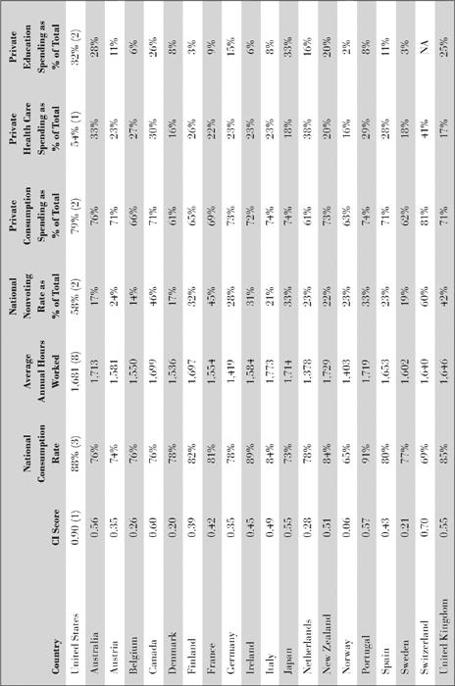

Though I can’t prove that America’s mass-media culture, ubiquitous advertising, and long hours of daily TV watching are the fundamental causes of its tendency to let markets run rampant over social values, I can show that America represents the unhappy extreme of commercialism among the leading economies. To do this, I have created a Commercialization Index (CI) that aims to measure the degree to which each national economy is oriented toward private consumption and impatience rather than collective (public) consumption and regard for the future. My assumption is that the United States and other heavy-TV-watching societies will score high on the CI and that a high CI score will be associated with several of the adverse conditions plaguing American society.

I include six items in the Commercialization Index, each item designed to measure a distinct aspect of the public-private or current-future dimensions of social choice. In each case a higher score signifies a higher degree of commercialization:

- The national consumption rate (private plus government consumption as a share of GDP)

- The average hours worked per year by a full-time employee (low leisure time, high orientation to market consumption)

- The national nonvoting rate (lack of public participation)

- Private health care spending as a percentage of total national health care spending (health care as a private good rather than a public good)

- Private education spending as a percentage of total national education spending (education as a private good rather than a public good)

- Private consumption spending as a percentage of national (private plus public) consumption (private consumption as the dominant form of consumption)

To keep things simple, each of these measures is scaled from 0 to 1, with 1 being the most commercially oriented score. Each country’s overall Commercialization Index score is calculated as the simple average of the six component measures. The overall ranking and the six components are shown in

Table 8.1

.

The United States is by far the most commercialized country in the sample, followed by Switzerland. America ranks first in one of the six variables (the share of private health care spending) and second in three of the remaining five. Generally, the rankings on the various components of the index are highly correlated across the countries. Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States tend to rank high on most dimensions of commercialization. The Scandinavian social democracies—Denmark, Norway, and Sweden—tend to rank low on all dimensions.

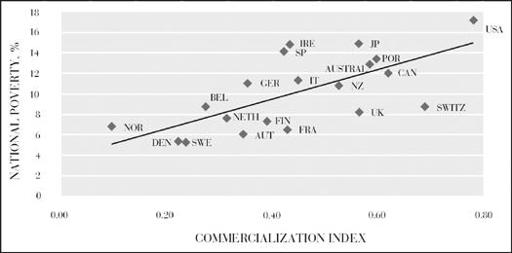

Highly commercialized societies like America are more likely to leave the poor behind. A high CI score is strongly associated with a high national poverty rate (measured by the OECD as the share of households below 50 percent of the median income), as we see in

Figure 8.3

. A high CI is also associated with a low level of development aid to poor countries, measured by official development assistance as a share of GDP. The high-CI countries are also those with the largest share of household income accruing to the richest 1 percent of households. It’s fair to say that in the highly commercialized economies, market values trump social values: the poor, both those at home and abroad, are more or less forgotten. I would surmise that in such societies, individuals are so overwhelmed by market values (bargaining, self-interest, competition) that they lose touch with other values (compassion, trust, honesty).

Figure 8.3: Relationship Between Commercialization Index and National Poverty Rate

Source: Data from the RTL Group and OECD.

Table 8.1: Commercialization Index

Source: OECD Statistical Databases and International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA). Note: U.S. rankings are in parentheses,

Whatever the cause, the United States is privately rich but socially poor. It caters to the pursuit of wealth but pays scant attention to those left behind. And though American culture emphasizes individualism and the pursuit of individual wealth perhaps more than any other society, that focus does not lead to greater happiness.

Of course such worries about hypercommercialism are not new. Karl Marx famously critiqued the “commodifaction” of social life from the perspective of the left. Yet trenchant criticism of excessive consumerism has also come from the religious and moral right. The famous German free-market thinker Wilhelm Röpke launched a famous and powerful critique against soulless advertising and mass consumerism in his book

A Humane Economy

in the middle of the twentieth century. Röpke observed that advertising “separates our era from all earlier ones as little else does, so much so that we might well call our century the age of advertising.”

10