The Price of Civilization: Reawakening American Virtue and Prosperity (16 page)

Read The Price of Civilization: Reawakening American Virtue and Prosperity Online

Authors: Jeffrey D. Sachs

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Economic Conditions, #History, #United States, #21st Century, #Social Science, #Poverty & Homelessness

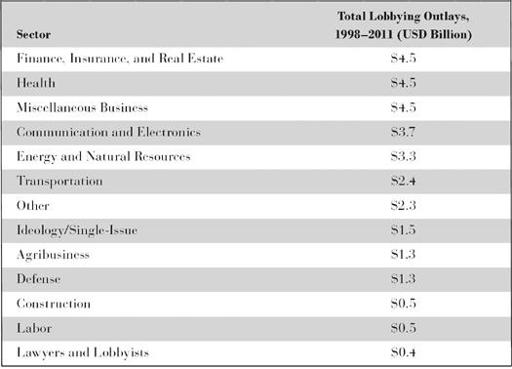

The list of top sectors in lobbying is like a who’s who of bad corporate behavior.

Table 7.1

shows the total lobbying outlays by sector during 1998–2011, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. The top sectors are the same ones where the economy is in the deepest trouble, and for reasons directly tied to regulatory failures: finance, health care, transport, agribusiness, and others. Each has landed remarkably cushy federal contracts, subsidies, tax breaks, and lax regulation and oversight. It should also be no surprise that finance, real estate, health care, and pharmaceutical companies rank among the lowest in public approval in Gallup polls, in all cases receiving “net negative” rankings by the public (in the August 2009 survey).

8

These industries epitomize the destructive policies produced by the corporatocracy, and the public knows it.

Table 7.1: Lobbying by Sector (1998–2011)

Source: Data from Center for Responsive Politics.

America’s Two Right-of-Center Parties

Every recent president has been caught in the same web of campaign financing and well-heeled special interests. Every candidate draws funds from the same sources, and all must hone their policy positions accordingly. Even as politics heats up in shouting matches on the air, the real range of policy prescriptions is shockingly narrow. For all the times that Obama has been accused by the right wing of dragging America to socialism, the actual content of Obama’s policies is often nearly indistinguishable from his predecessor’s. For all of the talk about the logjams in Washington, what have been the real differences between Bush and Obama?

- Bush wanted tax cuts for 100 percent of households; Obama campaigned on tax cuts for 95 percent of the households but, when the deadline approached in December 2010, agreed to extend tax cuts for all.

- Bush supported large deficits, in order to maintain low taxes and high military spending; Obama also supported large deficits, mainly as a macroeconomic stimulus.

- Bush bailed out the banks and the auto companies; Obama continued those policies.

- Bush supported immigration reform but was blocked by his own party; Obama favors immigration reform but is blocked by both parties.

- Bush favored nuclear power and deep-sea oil drilling; Obama favors nuclear power and deep-sea oil drilling.

- Bush filled his White House with Goldman Sachs and Citigroup executives; Obama has done the same.

There are, of course, several reasons for these very narrow differences. Most important, each party pulls its campaign contributions from the same sources and therefore does not deviate far from the core messages of the corporate sector and high-net-worth individuals. America has thereby been pulled to a “median” that is politically far to the right of center and to the right of the public’s true values. On issue after issue, Washington politics back the special interests rather than broad public values.

We can consider America’s political system today to be not so much a true democracy as a stable

duopoly

of two ruling parties, whose members shout at each other from time to time but which both basically stand for many of the same things when it comes to issues touching the interests of business, the rich, and the military. Both parties are instruments of powerful businesses and the rich. Rather than aiming for the median voter, as in the textbook two-party election theory, both parties actually aim to the

right

of center to attract high-income campaign contributors. For the Republican Party, this is easy and natural. For the Democrats, who ostensibly represent the needs of the poor, it means party leaders such as Presidents Clinton and Obama, who relentlessly side with Wall Street and the rich and just as relentlessly apologize to their base.

The overpowering role of money in politics has led to a fairly stable bipartisan consensus among politicians (though not necessarily the broad public) on five major points of policy in the past thirty years that reflect a fidelity to vested interests. These are low marginal tax rates for the rich, as sponsored by campaign contributors; the contracting of public services to well-connected private interests; the neglect of the budget deficit when voting on tax and spending issues, leaving the debt to future generations; the favoring of large military outlays, even as domestic spending is squeezed; and the lack of serious long-term budget planning. These five policy biases have been maintained through the thick and thin of presidents since Reagan.

The famous “triangulation” of Obama and Clinton with conservative positions is designed less to win centrist voters than to fill

campaign coffers with corporate funds. Corporatocracy, the over-representation of corporate and wealthy interests, is the essential feature of the duopoly. Campaign financing and lobbying are the key elements that keep the system intact.

The compromises made with the rich are consistently out of line with public opinion. The public desires to tax the rich more heavily, cut military spending, and develop renewable energy alternatives to oil. The outcome instead is tax cuts for the rich, unchecked military spending, and a continued stagnation in alternatives to oil, gas, and coal.

Both parties have consistently downplayed the importance of budget balance in favor of other political objectives. Reagan’s supply-side advisers argued that tax cuts would spur enough growth to pay for themselves. Obama’s stimulus supporters have argued something analogous: that deficits in the midst of a downturn have little or no longer-run cost, and even that deficit cutting in a recession is not feasible. These are both magical arguments without any empirical support but lots of ideological fervor. More important, they are arguments of convenience, allowing each party to favor its constituencies with short-term benefits (more tax cuts or spending increases) while downplaying the buildup of debt that will inevitably ensue. There have been only two short-lived exceptions to the chronic neglect of budget deficits. The first was George H. W. Bush, who broke his 1988 campaign pledge of “no new taxes” in order to reduce the budget deficit in 1990. The second was Bill Clinton, who pushed a modest hike in the top income tax rate (from 31 to 39.6 percent) and agreed to Republican-led budget cuts that helped move the budget to a temporary surplus at the end of the 1990s, albeit one that was quickly reversed under George W. Bush.

The duopoly also applies to foreign policy. Both parties view the Middle East and its greater neighborhood (stretching from the Horn of Africa and Yemen in the west to Afghanistan in the east) as the core theater of U.S. foreign policy, with the primary concern the continued flow of Middle East oil to the world economy. Carter

enunciated a military doctrine that any threat to the flow of Middle East oil would be viewed as a security threat to the United States. There have been marginal differences in military proclivities between the two parties, with Bush Jr. being the most trigger-happy of recent presidents, but the differences should not be exaggerated. Obama not only retained Bush’s secretary of defense but also expanded the war in Afghanistan while drawing down troops in Iraq. As the author and former army colonel Andrew Bacevich makes clear, the core U.S. military doctrine—based on the global projection of force—has remained constant on a bipartisan basis for more than forty years.

9

The final feature of the two-party duopoly during the past three decades has been the willful neglect of longer-term thinking in government. The only place where even a modicum of long-term budgeting takes place is the Congressional Budget Office, which provides a nonpartisan budget “score” of legislative proposals, usually on a ten-year time horizon, though occasionally longer. But this budget score is a far cry from systematic thinking about long-term issues: infrastructure, budget balance, education, energy policy, and climate change. It is hard to think of a single recent case in which the U.S. government, led by either party, has produced a quantitative assessment of any long-term challenge and then followed through with a considered policy reform based on that assessment. For decades, Washington has been improvising through the repeated alternations of power.

The Four Big Lobbies

The corporatocracy is a quintessential example of a feedback loop. Corporate wealth translates into political power through campaign financing, corporate lobbying, and the revolving door of jobs between government and industry; and political power translates into further wealth through tax cuts, deregulation, and sweetheart contracts

between government and industry. Wealth begets power, and power begets wealth.

Four key sectors of the American economy exemplify this feedback loop. The military-industrial complex is perhaps the most notorious example. As Eisenhower famously warned in his farewell address in January 1961, the linkage of the military and private industry created a political power so pervasive that America has been condemned to militarization, useless wars, and fiscal waste on a scale of many tens of trillions of dollars since then.

10

The second powerful lobby is the Wall Street–Washington complex, which has steered the financial system toward control by a few politically powerful Wall Street firms, notably Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup, Morgan Stanley, and a handful of other financial firms. The close ties of finance and Washington paved the way for the 2008 financial crisis and the megabailouts that followed, through reckless deregulation followed by an almost complete lack of oversight by government. Wall Street firms have provided the top economic policy makers in Washington during several administrations, including the likes of Donald Regan (Merrill Lynch) under Reagan, Robert Rubin (Goldman Sachs) under Clinton, Hank Paulson (Goldman Sachs) under Bush Jr., and several Wall Street–connected senior officials under Obama (including William Daley, Larry Summers, Gene Sperling, and Jack Lew).

The third sector is the Big Oil–transport–military complex that has put the United States on the trajectory of heavy oil import dependence and a deepening military trap in the Middle East. Since the days of John D. Rockefeller and the Standard Oil Trust a century ago, Big Oil has loomed large in American politics and foreign policy. Big Oil teamed up with the automobile industry to steer America away from mass transit and toward gas-guzzling vehicles driving on a nationally financed highway system. Big Oil has consistently and successfully fought the intrusion of competition from non-oil energy sources, including nuclear, wind, and solar power. Big Oil has been at the side of the Pentagon in making sure that

America defends the sea-lanes to the Persian Gulf, in effect ensuring a $100 billion–plus annual subsidy for a fuel that is otherwise dangerous for national security. And Big Oil has played a notorious role in the fight to keep climate change off the U.S. agenda. ExxonMobil, Koch Industries, and others in the sector have underwritten a generation of antiscientific propaganda to confuse the American people.

The fourth of the great industry-government tie-ups has been the health care industry, America’s single largest industry today, absorbing no less than 17 percent of GDP. The key to understanding this sector is to note that the government partners with industry to reimburse costs with little systematic oversight and control. Pharmaceutical firms set sky-high prices protected by patent rights; Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurers reimburse doctors and hospitals on a cost-plus basis; and the American Medical Association restricts the supply of new doctors through the control of placements at American medical schools. The result of this pseudo–market system is sky-high costs, large profits for the private health care sector, and no political will to reform.

Recent Case Studies of Corporatocracy

Now it’s time to see the corporatocracy at work, to understand how the lobbies dominate policy making at the expense of the nation and contrary to the expressed opinions of the American people. I will explore these workings in four recent case studies.

Case 1: The Extension of Tax Cuts for the Rich

During the 2008 campaign, President Obama said he would support a rollback of the Bush-era tax cuts on the richest 5 percent of taxpayers but sustain the Bush tax cuts for the remaining 95 percent of the population. His campaign pledge to tax the rich involved little more

than a rise in the marginal tax rate from 35 percent to 39.6 percent on households with incomes above $250,000. Despite all the sound and fury on tax policy, there was in fact little difference between John McCain and Obama, a difference in essence of 4.6 percentage points on the highest incomes.

Even more tellingly, when push finally came to shove in 2010 on whether to extend the Bush tax cuts even for the rich, Obama rather quickly sided with the Republicans in favoring an across-the-board extension of the Bush-era tax cuts, including for the richest households. The two-party duopoly held firm, despite the crying need for more revenues to stanch the hemorrhaging of red ink.