The Price of Civilization: Reawakening American Virtue and Prosperity (2 page)

Read The Price of Civilization: Reawakening American Virtue and Prosperity Online

Authors: Jeffrey D. Sachs

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Economic Conditions, #History, #United States, #21st Century, #Social Science, #Poverty & Homelessness

Much of this book is about the social responsibility of the rich, roughly the top 1 percent of American households, who have never had it so good. They sit at the top of the heap at the same time that around 100 million Americans live in poverty or in its shadow.

1

I have no quarrel with wealth per se. Many wealthy individuals are highly creative, talented, generous, and philanthropic. My quarrel is with poverty. As long as there is both widespread poverty and booming wealth at the top, and many public investments (in education, child care, training, infrastructure, and other areas) that could reduce or end the poverty, then tax cuts for the rich are immoral and counterproductive.

This book is also about planning ahead. I’m a firm believer in the market economy, yet American prosperity in the twenty-first century also requires government planning, government investments, and clear long-term policy objectives that are based on the society’s shared values. Government planning runs deeply against the grain in Washington today. My twenty-five years of work in Asia have convinced me of the value of long-term government planning—not, of course, the kind of dead-end central planning that was used in the defunct Soviet Union, but long-term planning of public investments for quality education, modern infrastructure, secure and low-carbon energy sources, and environmental sustainability.

The Mindful Society

“The unexamined life is not worth living,” said Socrates.

2

We might equally say that the unexamined economy is not capable of securing our well-being. Our greatest national illusion is that a healthy society can be organized around the single-minded pursuit of wealth. The ferocity of the quest for wealth throughout society has left Americans exhausted and deprived of the benefits of social trust, honesty, and compassion. Our society has turned harsh, with the elites on Wall Street, in Big Oil, and in Washington among the most irresponsible and selfish of all. When we understand this reality, we can begin to refashion our economy.

Two of humanity’s greatest sages, Buddha in the Eastern tradition and Aristotle in the Western tradition, counseled us wisely about humanity’s innate tendency to chase transient illusions rather than to keep our minds and lives focused on deeper, longer-term sources of well-being. Both urged us to keep to a middle path, to cultivate moderation and virtue in our personal behavior and attitudes despite the allures of extremes. Both urged us to look after our personal needs without forgetting our compassion toward others in society. Both cautioned that the single-minded pursuit of wealth

and consumption leads to addictions and compulsions rather than to happiness and the virtues of a life well lived. Throughout the ages, other great sages, from Confucius to Adam Smith to Mahatma Gandhi and the Dalai Lama, have joined the call for moderation and compassion as the pillars of a good society.

To resist the excesses of consumerism and the obsessive pursuit of wealth is hard work, a lifetime challenge. To do so in our media age, filled with noise, distraction, and temptation, is a special challenge. We can escape our current economic illusions by creating a

mindful society

, one that promotes the personal virtues of self-awareness and moderation, and the civic virtues of compassion for others and the ability to cooperate across the divides of class, race, religion, and geography. Through a return to personal and civic virtue, our lost prosperity can be regained.

CHAPTER 2.

Prosperity Lost

There can be no doubt that something has gone terribly wrong in the U.S. economy, politics, and society in general. Americans are on edge: wary, pessimistic, and cynical.

There is widespread frustration with the course of events in America. Two-thirds or more of Americans describe themselves as “dissatisfied with the way things are going in the United States,” up from around one-third in the late 1990s.

1

A similar proportion of Americans describe the country as “off track.”

2

This is coupled with a pervasive cynicism about the nature and role of government. Americans are deeply estranged from Washington. A large majority, 71 percent to 15 percent, describes the federal government as “a special interest group that looks out primarily for its own interests,” a startling commentary on the miserable state of American democracy. A similarly overwhelming majority, 70 percent to 12 percent, agrees that “government and big business typically work together in ways that hurt consumers and investors.”

3

The U.S. government has lost the confidence of the American people in a way that has not previously occurred in modern American history or probably elsewhere in the high-income world. Americans harbor fundamental doubts about the motivations, ethics, and competency of their federal government.

This lack of confidence extends to most of America’s major institutions. As we see in the data from a recent opinion survey (see

Table 2.1

), the public deeply distrusts banks, large corporations, news media, the entertainment industry, and unions, in addition to their distrust of the federal government and its agencies. Americans are especially skeptical of the overarching institutions at the national and global level—Congress, banks, the federal government, and big business—and more comfortable with the institutions closer to home, including small churches, colleges, and universities.

Table 2.1: The Public’s Negative Views of Institutions Are Not Limited to Government

Source: Pew Research Center for the People & the Press, April 2010.

Americans’ loss of confidence in its institutions is matched by a loss of confidence in one another. Sociologists, led by Robert Putnam, have shown the decline of civic-mindedness in American society. Americans participate less in social affairs (“bowling alone” in Putnam’s now-famous phrase) and have much less trust in one

another. They have retreated from the public square to the home, spending their nonwork time in front of the computer, TV, or other electronic media. The loss of trust is especially high in ethnically diverse communities, where the population is “hunkering down,” in Putnam’s words.

4

The two main political parties are not showing a way out of the crisis. Even when the fights between them are vicious—on taxes, spending, war and peace, and other issues—they actually hew to a fairly narrow range of policies, and not ones that are solving America’s problems. We are paralyzed, but not mainly by disagreements between the two parties, as is commonly supposed. We are paralyzed, rather, by a shared lack of serious attention to our future. We increasingly drift between elections without serious resolution of a long list of deep problems, whether it’s the gargantuan budget deficit, wars, health care, education, energy policy, immigration reform, campaign finance reform, and much more. Each election is an occasion to promise to reverse whatever small steps the preceding government has taken.

The general deterioration of conditions is taking its toll on life satisfaction in the country. Americans have long been a satisfied population. Why shouldn’t they be, living in one of the world’s richest, freest, and safest places? Yet we should listen more closely to the message over recent decades when Americans have been asked about their life satisfaction or happiness. As the economist Richard Easterlin discovered many years ago, America hit a kind of ceiling on self-reported happiness (sometimes called subjective well-being, or SWB) several decades back.

5

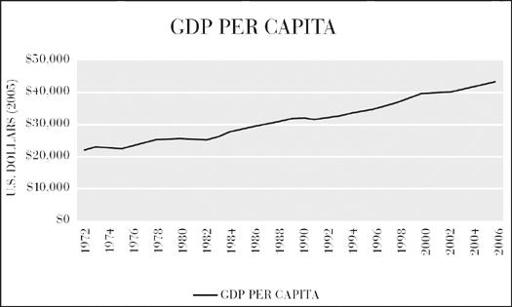

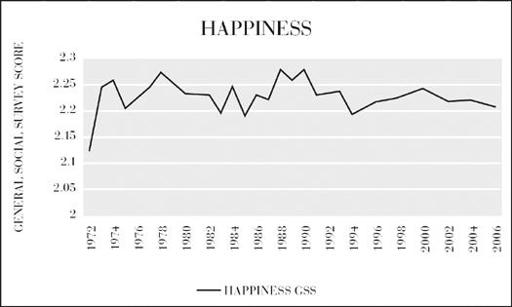

The trend line of happiness between 1972 and 2006 is flat, varying between 2.1 and 2.3 on a scale from 1 (not happy) to 3 (happy), even as per capita GDP doubled from $22,000 to $43,000, as we see in

Figure 2.1

.

Even as the GDP per person has risen, the happiness of Americans has not changed and perhaps has even declined among women, at least according to a recent careful study.

6

The citizens of many other countries now report a higher level of life satisfaction, putting the United States no higher than nineteenth in a recent international comparison by Gallup International.

7

Americans are running very hard to pursue happiness but are staying in the same place, a trap that psychologists have christened the Hedonic Treadmill.

8

Figure 2.1: U.S. GDP per Capita and Happiness Trend Line, 1972–2006

Source: Data from U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Source: Data from General Social Survey.

The Jobs and Savings Crisis

America’s unemployment rate is nearly 9 percent of the labor force and has been stuck there for two years.

9

In all, 8.6 million jobs were shed from the peak employment in 2007 to the trough in 2009. Even before the current crisis, the 2000s had the lowest growth of jobs of any decade since World War II.

10

The job-market pain is not felt evenly. The unemployment rate is by far the highest among lower-skilled workers, reaching 15 percent among workers with less than a high school education and 10 percent of those with a high school diploma or some college. Workers with at least a bachelor’s degree have come through the crisis with more modest, though still very real, losses. Their unemployment rate hovered around 4 percent as of December 2010, up from around 2 percent in 2006.

11

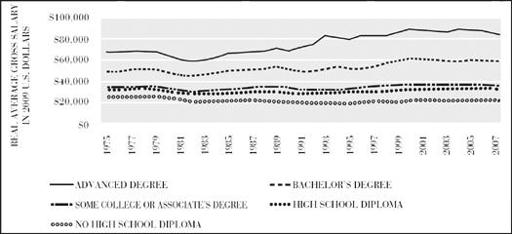

The widening gap in labor-market outcomes of those with and without at least a bachelor’s degree is a theme to which we will return many times. In the figure below, we see the trajectory of earnings of workers according to their educational attainment, all relative to a high school diploma. In 1975, those with a bachelor’s degree earned around 60 percent more than those with a high school diploma. By 2008, the gap was 100 percent.

Figure 2.2: Real Salary Growth Limited to Bachelor’s and Advanced Degree Holders, 1975–2007

Source: Data from U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey (2008).

The 2008 financial meltdown also deepened the financial distress of millions of Americans who kept their jobs but lost their homes and savings. The fall in housing prices beginning in 2006 spelled the end of a couple of decades in which middle-class households treated their homes as ATM machines, drawing on the ostensible value of the home through home equity loans. With the collapse of the housing bubble, millions of households found that their homes were now worth less than their mortgages, leading them to default on their mortgage payments.

This widespread financial distress is the end stage of a generation-long decline in Americans’ propensity to save. The national savings rate, which measures how much of the nation’s income is put aside for the future, tells a striking story. Saving for the future is the main kind of self-control needed for a household’s sustained well-being. Yet starting in the 1980s, the personal savings rate out of disposable income began to fall sharply, as we see in

Figure 2.3

, and began a small recovery only after the calamitous 2008 financial crisis. In the three decades leading up to 2008, the nation as a whole, through countless individual decisions of households, lost the self-discipline to save for the future.