The Price of Civilization: Reawakening American Virtue and Prosperity (14 page)

Read The Price of Civilization: Reawakening American Virtue and Prosperity Online

Authors: Jeffrey D. Sachs

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Economic Conditions, #History, #United States, #21st Century, #Social Science, #Poverty & Homelessness

The winners include not only the owners of physical capital (who can shift operations abroad) and financial capital (who can invest funds abroad) but also owners of human capital, who can export skill-intensive services to the emerging economies. This includes Wall Street bankers, corporate lawyers, high-tech engineers, designers, architects, senior managers, and others with advanced degrees and who work in high-tech fields. Finally, athletes, performing artists, and brand-name products are all given a boost by an expanded global market. Many U.S. and European brands are now enjoying booms by expanding into the emerging economies, where hundreds of millions of consumers with rapidly rising incomes are eager to follow in the path of their Western counterparts.

Among American workers, the biggest losers by far are those with a low level of education. This is because most of the new entrants to the global labor market in China and India also have a high school diploma or less. These emerging-economy workers enter labor-intensive export sectors such as apparel cutting and stitching, shoemaking, furniture making, electronic appliance assembly, and standardized manufacturing processes such as plastic injection. As the prices of these globally traded labor-intensive products are pushed down, the wages of low-skilled workers in the United States are also pushed down. U.S. firms in those sectors also shift their operations to China, leaving their own workers unemployed or having to accept sharp cuts in wages to remain employed.

One of the key realities of the new globalization is the ever-expanding range of competition between U.S. and emerging-economy workers. Half a century ago, American workers did not have to fear much competition from abroad, least of all from low-wage countries. Transport and logistics costs were simply too high for American firms to source in Asian low-income countries. Moreover, most of

those countries were closed to investment from the United States. Yet as transport, communications, and logistics costs began to fall, and as those economies opened to trade and investment, some low-tech industries could relocate factories abroad. As costs fell further, it became possible for even high-tech industries, such as computer and other advanced machinery manufacturing, to relocate just parts of the value chain—for example, final assembly operations—abroad. As costs fell still further, due mainly to the Internet, it became possible to shift back-office jobs, such as accounting and human resources operations, from the United States to India (favored over China because of its English-speaking workers), all enabled by the Internet. Now American workers compete directly with their counterparts in the emerging economies without companies’ needing to shift physical capital, only to have online connectivity.

A key result of the new globalization has therefore been a huge change in income distribution in the United States. Capital owners have been the big winners, enjoying a rise in pretax returns and a cut in the tax rates levied on them. Workers with low educational attainments have tended to lose, as they are directly in the line of competition from the emerging economies. And the federal government has exacerbated these trends. First market forces raised the incomes of the rich, and then the government, caught up in a race to the bottom with counterparts, cut both personal and corporate income taxes, thereby giving an added boost to the rich, while turning around to slash public spending for the poor.

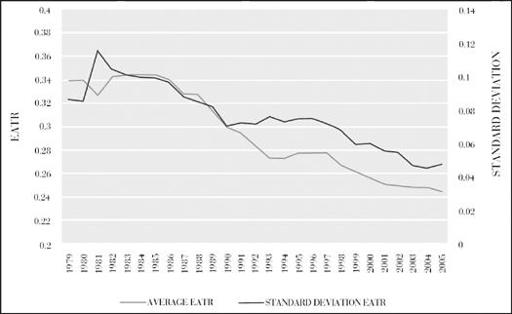

Throughout the high-income economies, governments have cut the effective average tax rate (EATR) on corporate income, and the spread in effective tax rates across countries narrowed as well. Both the decline of EATRs and the narrowing of the spread of EATRs are shown in

Figure 6.2

for nineteen high-income countries, including the United States. The careful statistical study from which this figure is taken demonstrates that “increased capital mobility (FDI) has a negative impact on the corporate tax rate.”

12

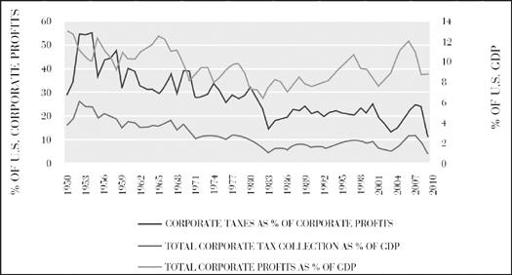

The effective U.S. corporate tax rate shows the same decline as in other high-income countries. America’s EATR declined from 30 to 40 percent during the 1960s to less than 30 percent from the mid-1970s onward, and is currently under 20 percent (

Figure 6.3

). One part of that decline reflects the greater ability of U.S. companies to hide their profits in offshore tax havens, with the implicit or explicit support of the Internal Revenue Service. The upshot is a decline in the share of GDP paid in federal corporate taxes, from an average of 3.8 percent in the 1960s to just 1.8 percent in the 2000s.

13

Figure 6.2: Effective Average Tax Rate in High-Income Countries, 1979–2005

Source: Data from Alexander Klemm, “Corporate Tax Rate Data,” Institute for Fiscal Studies, August 2005.

Figure 6.3: U.S. Corporate Taxes, 1950–2010

Source: Data from U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.

The race to the bottom exists not only in falling corporate tax rates but in many other aspects as well, such as the weakening of labor standards, financial sector deregulation, and lack of enforcement of environmental standards. As one consequential example, New York and London were in a dramatic race to the bottom regarding financial deregulation during the past twenty years, to the delight of the financial firms on Wall Street and in the City of London. The end result was to feed the massive financial bubble that finally exploded in 2008. Dozens more places, ranging from Dublin to Dubai, have been slashing corporate tax rates and converting themselves into destinations for tax evasion.

There is one overarching solution to the race to the bottom: international cooperation. All countries are suffering from the decline in corporate tax rates and the downward pressures on financial, environmental, and other regulatory standards. By banding together to set minimum international norms, such as a common approach to eliminating tax havens and a common standard of financial and environmental regulation, all countries can gain. Of course, with their overweening power, corporate lobbies routinely short-circuit such attempts at global cooperation by successfully playing off one government against another.

The Depletion of Natural Resources

The new globalization poses one more enormous problem: the depletion of vital primary commodities such as freshwater and fossil fuels, and long-term damage to the earth’s ecosystems under the tremendous stresses of worldwide economic development. For a long time, economists ignored the problems of finite natural resources and

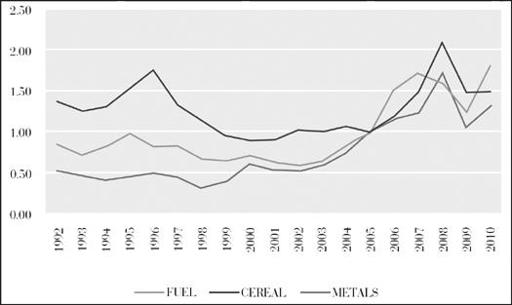

fragile ecosystems. This is no longer possible. The world economy is pressing hard against various environmental limits, and there is still much more economic growth—and therefore environmental destruction and depletion—in the development pipeline. The explosive growth of production in China, India, and other emerging economies is already pushing world prices of food and feed grains, coal, oil, and countless other primary commodities sky-high, indicating an era of much greater scarcity and resource depletion. The surge in primary commodity prices in recent years, including fuels (oil, gas, and coal), minerals (copper, aluminum, iron ore, and others), and cereal grains (wheat, maize, rice, and others), is shown in

Figure 6.4

. The commodity price indexes are divided by the U.S. GDP price deflator to obtain inflation-adjusted indexes for each commodity group. It was only the steep economic downturn in 2009 that brought commodity prices down from their 2008 peaks.

The scarcity problems may be even more serious in areas where market prices are not available to warn us of impending environmental crises. This is the case of climate change, deforestation, loss of biodiversity, land erosion, and many kinds of large-scale pollution. In all those cases, unprecedented environmental destruction is under way and getting worse, but without market signals in place to guide us back to sustainable technologies and business practices.

Figure 6.4: Primary Commodity Prices (Inflation-Adjusted), 1992–2010

Source: Data from International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook, 2011.

The issue of environmental sustainability is a huge one that could take us too far afield here. I earlier tried to provide an overview of the interconnected and complex challenges in my book

Common Wealth

. In the current context, though, I would like to emphasize that America’s sustained prosperity will require solutions to the rapidly encroaching resource pressures.

There are two main obstacles to a sustainable trajectory. First, the scientific and technological know-how to deploy more sustainable technologies (such as massive supplies of low-carbon energy from solar power) still needs large-scale research and development. Second, we need to overcome the power of corporate lobbies in order to impose regulations and market incentives that will steer markets toward sustainable solutions. So far, the corporate lobbies of the polluting industries have blocked such measures.

Free-market economists, once again including Hayek and Friedman, have recognized the need for public action to protect the natural environment. And Americans have consistently agreed, expressing strong environmental sentiments on a wide range of environmental challenges.

14

Yet this basic truth has not yet found political expression in the United States because of the power of Big Oil and Big Coal. In

chapter 10

, I’ll suggest some possible policies to break the hammerlock of these special interests.

America’s Failed Response to the New Globalization

To sum up the findings of this chapter, America has failed to respond effectively to the challenges of the new globalization. The manufacturing sector has shrunk as factories and employment have been shifted overseas. The working class, especially, has been squeezed. Economic policies did not exactly stand still but in fact

responded perversely: taxes on the rich were cut; the manufacturing sector was allowed to decline in the face of growing foreign competition; employment in construction was temporarily spurred by easy money from the Fed and subprime lending, but that expedient lasted only until 2007, when the subprime bubble burst. The 2008 financial crisis was therefore a crisis of utterly mismanaged globalization. The United States had responded to the long-term loss of manufacturing competitiveness by the temporary expedient of a housing boom. When the boom was followed by a collapse, U.S. unemployment soared and the emptiness of U.S. short-termism was exposed for all to see. What is remarkable is that even after the collapse of the bubble, Washington was still unable to come up with any long-term, serious responses to America’s waning competitiveness, instead turning again to the very same policy mix that had failed previously: easy money, tax cuts, large budget deficits, and, starting in 2011, cuts in government outlays on education, infrastructure, science, and technology, the very areas in which the United States needs to invest to regain its long-term competitiveness.

CHAPTER 7.

The Rigged Game