The Parthenon Enigma (13 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

Modern interpreters have called this Archaic building by many names: Hekatompedon (“Hundred-Footer”), Temple H, H-Building, the Ur-Parthenon, and the Bluebeard Temple,

41

this last designation referring to a unique sculptural group usually assigned to the corner of one of the pediments.

42

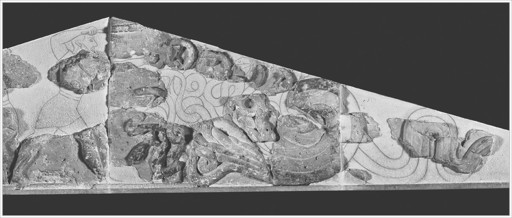

It shows a weird and wonderful human-headed, three-bodied monster with spreading wings incised on the back wall of the tympanum and a lower torso that terminates in three entwined snaky coils (above and insert

this page

, top). The grinning, mustachioed, and wide-eyed faces of the beast are trimmed at the chin by pointed beards highlighted in blackish-blue paint: hence the nickname. Scholars have long debated the identity of this beast.

43

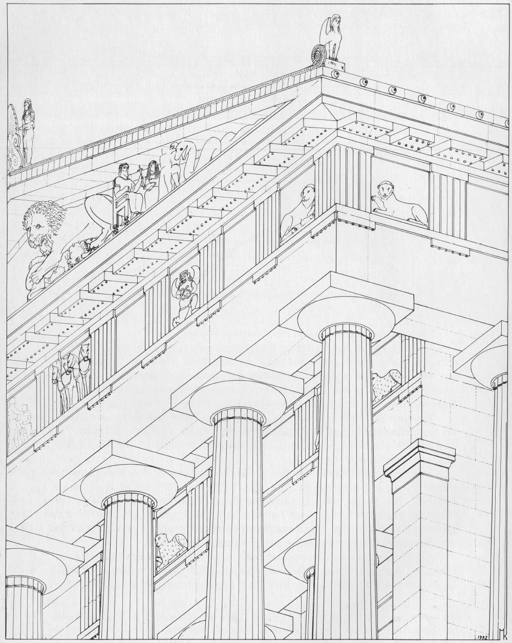

Reconstruction drawing of façade of Bluebeard Temple (Hekatompedon?) by M. Korres. (illustration credit

ill.14

)

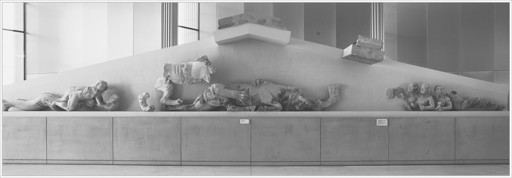

Bluebeard Temple pediment (Hekatompedon?). Athens, Acropolis Museum. (illustration credit

ill.15

)

As it appears so early in the history of architectural sculpture, this fantastic creature has few iconographic parallels. The closest is found not in monumental stone but painted on a Chalkidean water jug dated some thirty years later (insert

this page

, bottom).

44

The vase shows a very similar composite with human head (albeit only one), giant bird wings, and legs in the form of viper coils. This monster, too, is wide-eyed with a pointed beard and must represent Typhoeus or Typhon, the most hideous monster of the primordial era. By some accounts, he was the last son of

Gaia and

Tartaros and known as the Father of All

Monsters. But in the

Homeric Hymn to Pythian Apollo

, Typhon is the child of

Hera alone—a kind of parallel to

Zeus’s child Athena.

45

Fascinatingly,

Hephaistos is also regarded as the son of Hera alone; both Typhon and the god of the fiery forge can be seen as the embodiment of Hera’s rage against Zeus. The presence of Typhon on the Hekatompedon pediment might in some way have reminded the Athenians of their problematic ancestor He- phaistos.

46

Whatever the case, Typhon represents a Greek counterpart

to the gruesome water reptiles slain by gods/heroes in Mesopotamian, Babylonian, Hittite, Vedic, and European lore.

47

Following the model of the great dragon figure that can only be slain once, Typhon meets his match in the storm god Zeus, who kills him with extraordinary violence.

Typhon appears amiable enough on the Chalkidean water jug, though he is shown on his very best behavior, beseeching Zeus to spare his life. Zeus, whose name appears in a painted inscription just before him, fiercely brandishes his flaming thunderbolt. Head-to-head in cosmic combat, the elegant, well-coiffed, and beautifully dressed Zeus confronts the wild, hairy, and lumbering behemoth Typhon in an archetypal clash between the younger generation of civilized

Olympians and the older generation of feral monsters, celestial and terrestrial.

When we turn to the

Bluebeard pediment, we find a demon creature similarly confronted by Zeus, very little of whose figure survives; just a small part of the storm god’s draped left arm can be made out in low relief against the tympanum wall. It is clear, however, that the arm stretches out toward the three-bodied monster, and it is likely that we have Zeus, once again, threatening with his thunderbolt.

Apollodoros tells us that Typhon was a beast like no other: taller than the mountains, his head brushing the stars. When he spread his arms, he could touch the farthest reaches of East and West.

48

Hesiod tells us that out of Typhon’s shoulders came “a hundred fearsome snake-heads with black tongues flickering.”

49

The Bluebeard monster’s chest and shoulders are, indeed, pierced by holes with traces of lead surviving within them, where twelve small limestone snakes may once have been attached.

50

Writing centuries later, Apollodoros similarly reports that from the monster’s thighs down, huge vipers emitted a long hissing sound: “Such and so great was Typhon when, hurling kindled rocks, he made for the very heaven with hissing and shouts, spouting a great jet of fire from his mouth.”

51

We should not underestimate the “acoustical effect” of monstrous creatures portrayed in Archaic Greek sanctuaries. We are at a disadvantage today, our sense of realism persuaded only by Dolby Surround sound. The ancients were far more suggestible, and the evocation of sound completes pictures and brings deeper understanding to how the images were received. Looking at the deliberately openmouthed Typhon on the Chalkidean vase or at the beseeching hand gesture of the Bluebeard monster, we must try to imagine what those versed in Hesiod’s

description of the beast would have heard: “There were voices in all his fearsome heads, giving out every kind of indescribable sound. Sometimes they uttered as if for the gods’ understanding, sometimes again the sound of a bellowing bull whose might is uncontainable and whose voice is proud, sometimes again of a lion who knows no restraint, sometimes again of a pack of hounds, astonishing to hear; sometimes again he hissed; and the long mountains echoed below.”

52

These susurrous sounds and clamor brought the narrative to life, palpably inducing the intended emotional response of fear.

Zeus is angry and unmoved by the monster’s clattering arsenal. He unleashes the full force of the elements, inciting a horrifying din of his own with fire, water, and wind. Hesiod describes it: “A conflagration held the violet-dark sea in its grip, both from the thunder and lightning and from the fire of the monster, from the tornado winds and the flaming bolt. All the land was seething, and sky, and sea; long waves raged to and fro about the headlands from the onrush of the immortals and an uncontrollable quaking arose.”

53

The Bluebeard-Typhon holds out in his hands a wave, a flame, and a bird, signaling the cache of water, fire, and wind that he will surrender to Zeus if only he is spared. But Zeus stands firm and Typhon is destroyed. A full blast of celestial and terrestrial tumult is thus effectively conjured in the single image of the Acropolis pediment’s Bluebeard monster.

At the left of the gable, Zeus’s son Herakles is shown subduing the water serpent Triton (

this page

and insert

this page

, top).

54

This can now be understood as a parallel scene in which the father-son duo tame the forces of nature and the cosmos across two generations: Zeus dispatches Typhon, while Zeus’s son Herakles kills Poseidon’s son Triton. And, of course, Triton has his own special

genealogical connection to the myth narrative of Athens, having served as Athena’s foster father following her birth near the lake or the river Triton in Libya. Indeed, the Bluebeard pediment is framed with imagery evoking the north Libyan wetlands where Triton lived and this battle with Herakles took place. Some forty fragments from the underside of the raking cornice show two forms of brightly painted, incised lotus flowers (insert

this page

, bottom); twenty others show waterfowl, including storks and sea eagles.

55

The clash of Zeus and Typhon similarly took place at the seaside, alternatively set along the coasts of Syria and Cilicia. According to one tradition, Zeus lures Typhon out of his pit with the promise of a fish feast

by the seashore. In another, Typhon hides Zeus’s weapons and sinews within his cave near the sea.

56

The lotus and waterfowl on the underside of the pediment’s raking cornice thus evoke the flora and fauna of Typhon’s lair as well as that of Triton. And thus the architectural frame is conceived as a “window” through which flying birds and marsh vegetation can be seen to set the stage on which gods, heroes, and monsters engage in cosmic clashes.

57

EXACTLY WHERE

the building that held the Bluebeard pediment stood and by what name it was called in antiquity remain a mystery. This is because the temple seems to have occupied the same spot where the Parthenon stands today. In any event, we cannot know what filled that space before the construction of the giant twenty-five-course platform on which the Parthenon still rests.

There is, however, another theory about the

placement of the Bluebeard Temple, one setting it to the north of the Parthenon where foundations are preserved from a temple built at the end of the sixth century. The so-called Old Athena Temple, as we have seen, will be destroyed by the Persians and supplanted by the

Erechtheion. But meanwhile, it stood on what have been nicknamed the

Dörpfeld foundations after the nineteenth-century Acropolis excavator

Wilhelm Dörpfeld (

this page

). He believed that the Bluebeard Temple had been set on the innermost foundations until the Old Athena Temple, built on the outermost, replaced it.

58

A marble metope from the Bluebeard Temple was salvaged after the temple’s destruction and inscribed with an important text, dated to 485/484

B.C.

Known as the “

Hekatompedon Inscription,” it names two distinct buildings that stood on the Acropolis: the Neos (referring to the Archaios Neos, or Old Athena Temple), and the Hekatompedon, or “Hundred-Footer.”

59

An excellent case has been made, contra Dörpfeld, for the identification of the Bluebeard Temple as the Hekatompedon, placing it on a site beneath the present Parthenon.

60

Indeed, the eastern room of the Parthenon was still called the

hekatompedon

in the fifth century

B.C.

and into the Roman era, perhaps reflecting a continuity in the naming of successive buildings on this site. And, as

Rudolph Heberdey documented long ago, every piece of Archaic poros sculpture found on the Acropolis was recovered from the area to the south of the Parthenon, between the temple and the south fortification wall.

61

Herakles battling the Lernaean Hydra, limestone pediment. Athens, Acropolis Museum. (illustration credit

ill.16

)

The Bluebeard Temple looks eastward for inspiration, not only in its narrative themes that focus so deliberately on

genealogical

succession myths and primordial battles between weather monsters and composite fiends, but also in its architectural forms. The incision of

lotus flowers beneath the cornice, the trumpet-shaped spouts that guided rainwater from its gutters, and the upturned edge of the roof above the gable’s apex in a tong-shaped embellishment, all these features show influence from the grand visual traditions of the ancient Near East.

62