The Oxford History of World Cinema (74 page)

Read The Oxford History of World Cinema Online

Authors: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

'misterioso' (despite its tempo marking of 'presto'). The more the repertory grew,

therefore, the more it seems to have fundamentally stayed the same, dictated by functional

requirements. Most pieces were expected to communicate their essential messages within

the space of a few bars, and often had to be broken off for the next cue. (In Bradford's list,

the shortest items are timed at thirty seconds, the longest three minutes.) Under the

circumstances, too much stylistic variety was suspect, but clich+00E9s were not (and they

made the music easier to play); moreover, familiar music (like the text that sometimes

went with it) might be valued highly for its allusive power, even if the reference was

imprecise.Similar considerations apply when evaluating compiled scores. As mixed in

their repertoire as cue sheets, many were stereotyped and seemingly haphazard, and all

were liable to be altered greatly from performance to performance. However, in several

cases both the selection and the synchronization of the music were carefully planned, and

led to results well above the norm. Three examples can serve to illustrate the range of

possibilities, as determined by types of films and circumstances of their

production/distribution.

1.

Walter C. Simon's music for the 1912 Kalem film The Confederate Ironclad: this

concise piano score, from an impressive series Simon created for Kalem in 1912 and

1913, was written for an advanced example of film narrative at that time. It fits the film

exceptionally well, and even though much of it is 'original', it is very much like a written

out cue-sheet score, with several pre-existent tunes.

2.

Breil's orchestral score for The Birth of a Nation can be seen as a Simon score writ

large, with the added interest of extensive original music involving more than a dozen key

leitmotivs, plus effective varieties of orchestral colour. By this time too, the repertoire has

been opened up to include a large number of nineteenth-century symphonic and operatic

works, more suitable for orchestral than piano accompaniments, and necessary for such a

film epic. There is no doubt that Griffith wanted music to be an integral part of the film

experience and, although the degree of his involvement cannot be known precisely, he

certainly played a role in encouraging Breil's ambitious efforts.

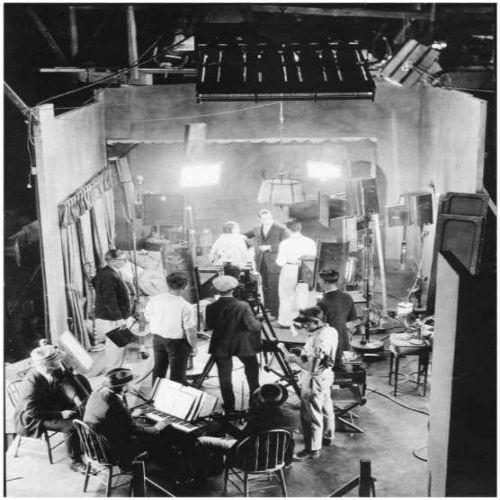

Mood music: an orchestra playing on the set to create the right atmosphere for a scene

from Warner Bros.' The Age of Innocence( 1924)

3.

The Axt-Mendoza score for Vidor's Big Parade follows the Breil model and is no

less a major piece of work, though with neither the same amount of original music nor the

personal stamp of the Griffith scores. Indeed, just as this later epic displays a smoother

style than Griffith's, the score shows how, by the mid-1920s, film music had Berlin, had

become a prime locale for the manufacture of scores, thanks to co-operative partnerships

between film producers, theatres, and music publishers.

Alongside compiled scores, original scores also increased in number in the 1920s, often

with remarkable results. A significant American example is Mortimer Wilson's music for

Raoul Walsh's 1924 The Thief of Bagdad: richly worked out in terms of both thematic

structure and orchestration, its lavish design is fitting for so opulent a film and presages

the achievements of Erich Korngold and the great composers of Hollywood scores in the

sound period. But the most impressive centres of original work were not in New York or

Hollywood, but in France, Germany, and Russia, where the fascination of artists and

intellectuals with the new medium led to unique collaborations.An important precedent

had been set in Europe much earlier, with Camille Saint-Saëns's score for the 1908film

d'art, L'Assassinat du Duc de Guise. As one might expect given the composer's many

years of experience and mastery of his craft, this score displays impressive thematic unity

and harmonic design, and is as polished as his many previous essays in ballet, pantomime,

and tone poem. Yet because it serves the film so well, the score has come to share the fate

of his other incidental pieces: mentioned in surveys but rarely studied, regarded more as a

fascinating transitional effort than as a convincing work of art.Of the many innovative

scores by composers who gravitated toward film in the 1920s, three in particular deserve

mention, each successful in attaining different goals.

1.

Eric Satie's score for Entr'acte ( 1924) shines as an antinarrative, proto-minimalist

gem; like Clair's film, it is designed both to dazzle and to disorient the audience, partly by

parodying the medium's customary product, partly by following a subtle formal logic

beneath a deceptively random surface.

2.

The Huppertz score for Metropolis ( 1927), commissioned for the Berlin premiére,

is one of the most peculiar examples known to survive of music following Wagner's

leitmotiv system, within an elaborate symphonic framework. Apparently following Lang's

original tripartite structure for the film, Huppertz divides his score into three independent

'movements' with the unusual names of 'Auftakt'. 'Zwischenspiel', and 'Furioso'. Like the

film, the music intermixes elements of nineteenthcentury melodrama and twentieth-

century modernism, and that is an essential part of its fascination: it strives

o

reinforce Lang's messages, and, while showing similarities to the American compilations

discussed above, employs a far more complex and varied musical vocabulary.

3.

Dmitri Shostakovich's score for Kozintsev and Trau berg 's New Babylon ( 1929)

ranks among the greatest examples of film music by a leading avant-garde composer of

any generation. Like the film, and somewhat like Satie's score for Entr'acte, the music is

in large part satirical, and depends for its effects on the distortion of well-known tunes,

especially the 'Marseillaise', as well as the use of French-style 'wrong-note' harmonies and

persistent motor rhythms -- all designed to offer both counterpoint and continuity to the

film's energetic montage. But the score (now available in a complete recording by the

Berlin Radio Symphony) also makes strong ideological points and attains tragic stature.

One great example occurs at the end of part vi, for scenes of the despair, desperate

resistance, and massacre of the Communards. While an old revolutionary pauses to play a

piano abandoned on the barricades, and while his comrades listen, visibly moved, the

orchestra pauses too, for the pit pianist's poignant fragment of 'source music'

( Tchaikovsky's Chanson triste); this trails off, and when the final battle begins, the

orchestra commences a prolonged agitato, which finally resolves into a thumpingly banal

waltz. Thus Shostakovich emphasizes the brutality of the French bourgeoisie, who are

seen applauding at Versailles, as if presiding over the scenes of carnage. No less pointed

is the music for the film's end, though it aims in an opposite direction: here Shostakovich

combines a noble horn theme for the Communards with the melody of the Internationale

in rough, dissonant counterpoint. The double purpose is to honour the martyrdom of the

film's heroes, and, more generally, to convey hope without clichéd sentiment. In a final

symbolic gesture, he ends the score virtually in mid-phrase, a fitting match to the film's

open-ended final three shots of the words 'Vive' | 'la' | 'Commune', seen scrawled as jagged

graffiti pointing dynamically past the edges of the frame.

Each of these three scores offers a unique solution to the challenging compositional

problems posed by an unusual film. Together, they crown the silent film's 'golden age',

and show that the medium had found ways to tap music's expressive potential to the

highest degree.

SILENT FILMS AND MUSIC TODAY

Even as Shostakovich completed his score, silent films were rapidly becoming obsolete. It

did not take long for many of the practices and materials of the period to be forgotten or

lost, but there have been efforts ever since to revive them. Cinematheques and other

venues where silent films continued to be screened went on providing piano

accompaniments, but often in a mode that was neither musically inspiring nor historically

accurate. At the Museum of Modern Art in New York between 1939 and 1967, however,

Arthur Kleiner maintained the tradition of using original accompaniments, availing

himself of the Museum's collection of rare scores; where scores were lacking, he and his

colleagues created scores of their own, which were reproduced in multiple copies and

rented out with the films.

In recent years scholarly work (particularly in the USA and Germany) has greatly

increased our knowledge of silent film music; archives and festivals (notably Pordenone

in Italy and Avignon in France) have provided new venues for the showing of silent films

with proper attention to the music; and conductors such as Gillian Anderson and Carl

Davis have created or re-created orchestral scores for major silent classics. This initially

specialist activity has spilled over into the commercial arena. In the early 1980s two

competing revivals of Abel Gance's Napoléon vied for public attention in a number of

major cities -- one, based on the restoration of the film by Kevin Brownlow and David

Gill, with a score composed and conducted by Carl Davis, and the other with a score

compiled and conducted by Carmine Coppola. Even wider diffusion has been given to

silent film music with the issue of videocassettes and laser discs of a wide range of silent

films, from Keystone Cops to Metropolis, all with musical accompaniment.

Both because of and despite these advances, however, the current state of music for silent

films is unsettled, with no consensus as to what the music should be like or how it should

be presented. (There was a lack of consensus during the silent period, too, but the

spectrum was not as broad as it is today.) Discounting the option of screening a film in

silence, an approach now generally held to be undesirable except in the very rare cases of

films designed to be shown that way, we can distinguish three basic modes of presentation

currently in use: (1) film screened in an auditorium with live accompaniment; (2) film,

video, or laser disc given a synchronized musical sound-track and screened in an

auditorium; (3) video or laser disc versions screened on television at home. Obviously, the

second and third modes, while more prevalent and feasible than the first, take us

increasingly further from the practices of the period. To show a silent film or its video

copy with a synchronized score on a sound-track is to alter fundamentally the nature of

the theatrical experience; indeed, once recorded, the music hardly seems 'theatrical' at all.

As for home viewing, whatever its advantages it forgoes theatricality to the point that any

type of continuous music, and especially thunderous orchestras and organs, can weigh

heavily on the viewer.

As for the scores themselves, they too can be divided into three basic types: (1) a score

that dates from the silent era, whether compiled or original (Anderson has made this type

of score her speciality); (2) a score newly created (and/or improvised) but intended to

sound like 'period' music -- the approach usually taken by Kleiner, by the organist

Gaylord Carter, and more recently by Carl Davis; (3) a new score which is deliberately

anachronistic in style, such as those created by Moroder for Metropolis in 1983, and by

Duhamel and Jansen for Intolerance in 1986. Thus, altogether there now exist nine

possible combinations of music and silent cinema (three modes of presentation, three

types of score), and all of them have yielded results both subtle and obtrusive, both

satisfying and offensive.

Particularly interesting in this respect are the cases where different versions have recently

been prepared of the same film. For Intolerance, for example, there now exist four

different versions. There is Anderson's, which is based on the Breil score and has been

performed in conjunction with a restoration of the film (by MOMA and the Library of

Congress) in a version as close as possible to that seen at the 1916 New York premiére.

There is a Brownlow-Gill restoration with Davis score, which has been screened both live