The Oxford History of World Cinema (71 page)

Read The Oxford History of World Cinema Online

Authors: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

produced Kyuha (Old School) films; samurai films with historical backgrounds. As soon

as Nikkatsu was established, several anti-trust companies were also ' formed. Among

them, Tenkatsu, established in March 1914, became the most competitive rival to

Nikkatsu. Before being absorbed into Nikkatsu, Fukuhodo had bought the rights to

Charles Urban's Kinemacolor for the purpose of releasing Urban's Kinemacolor films and

producing Japanese films shot by the process. Taking over these rights, Tenkatsu was

established to make Kinemacolor films to compete with Nikkatsu films. Tenkatsu, who

imitated Nikkatsu by making both Old School and New School films, also produced

rensageki, or chain drama, a combination of stage play and cinema using films for the

scenes that were difficult to represent live on the stage. The live action and filmic images

alternated in a 'chain' fashion. After one scene was played by actors on the stage, the

screen descended and the next scene was projected on to it for several minutes, and then

the actors played on the stage again. Tenkatsu was unusual in employing actresses for

these films as early as 1914.

The distinction between the Old School and New School was borrowed from the concept

of genre chiefly established in stage plays of the Meiji period. The Old School, which was

later called jidaigeki (period drama), was constituted, in most cases, by sword-play films

in which people in historical costume appeared, set in the periods before the Meiji

restoration. The New School, which was later called gendaigeki (modern drama),

consisted of films set in contemporary circumstances. The Old School was always based

around a superstar: Matsunosuke Onoe was Nikkatsu's most famous star, while Tenkatsu

had the very popular Shirogoro Sawamura. The cinema of stars was thus established first

and foremost by the period drama in Japan. In such films, stereotyped stories were

repeated again and again, and played by the same actors. This tradition of repetition

became one of the most particular traits in the history of Japanese cinema. Such stories as

Chushingura ('The loyal forty-seven retainers') have been made many times and continue

to be made to this day.

By 1914 there were nine film-producing companies in Japan. The largest one was

Nikkatsu, which released fourteen films a month from their two studios. Tenkatsu had

studios in Tokyo and Osaka and made fifteen films a month. The oldest company,

Komatsu, established in 1903, had ceased film production for a while, but began to

produce films again in a studio in Tokyo in 1913. In 1914 this company made six films a

month. The ephemeral company Nippon Kinetophone made a few sound films in the

same year. Tokyo Cinema and Tsurubuchi Lantern & Cinematograph were making news

films. In Osaka, there were some small companies like Shikishima Film, Sugimoto Film,

and Yamato On-ei. By 1915, when M. Kashii Film, the company that took over Pathé,

joined these antitrust companies, Nikkatsu's aspirations to monopolize the market were

dashed.

Masao Inoue's Taii no musume ('The daughter of the lieutenant', 1917), made at the newly

established Kobayashi Co., was quite different from the traditional New School films in

using westernized techniques. Adapted from the German film Gendarm Möbius ( Stellan

Rye, 1913), Taii no musume was inspired by its stylistically static direction, but Masao

Inoue used a flashback that the German film had not, and utilized close-ups that were

unusual in Japanese cinema at the time. In the period when the filmic was for the most

part constituted as a kind of illustration for the benshi's vocal skills, Inoue showed the

rhetorical sense in the picture itself. The image of the bride's trousseau being carried for

the wedding ceremony is reflected on the surface of a river, while the camera pans slowly

to catch the faces of people in the frame. Such westernized direction was rare in Japanese

cinema even in 1917. Inoue again used close-ups in his next film Dokuso ("The

poisonous herb', 1917), but in most Japanese films of this period, where oyama still

played the female roles, the close-up of the 'woman' was not effective.

There had been partial and sporadic attempts to westernize Japanese cinema even before

1910. For example, in the Yoshizawa Company's comedy films, which were heavily

influenced by French cinema, the main actor was a Max Linder imitator. But it was in the

late 1910s that some companies attempted to change the highly codified organization of

primitive Japanese cinema into the constitution of westernized reality; incorporating

realist settings, rapid shot development, and a move away from stereotyped subjects. This

was also the period when the role of director attained a new importance. In 1918 directors

like Eizo Tanaka and Tadashi Oguchi made changes to the dominant form of Nikkatsu's

New School films.

Although stereotypes could not be avoided totally in modern drama, films of the New

School did show more artistic ambition, particularly those produced in Nikkaten's.

Mukojima studio in the late 1910s. In Japanese arts in the post-Meiji period, artistic

ambition was widely considered to be a western concept, so that the value of art in Japan

could be made highbrow by conforming to the norms of western art. The westernization

of style was easier in modern drama than in period drama, and so it was here that the

developments took place.

The process of westernization in Japanese cinema, which included the phasing out of

oyama in favour of actresses, began in earnest in the late 1910s, spearheaded by the ideas

of the young critic and film-maker Norimasa Kaeriyama. Kaeriyama asserted that

Japanese cinema, which was only the illustration of the benshi's voice impersonations,

had to find a way for the narrative to be automatically formed by the filmic image, as seen

in the dominant form of European and American cinema. In 1918, when Nikkatsu allowed

Eizo Tanaka and Tadashi Oguchi to make westernized films on this principle, Tenkatsu,

accepting Kaeriyama's idea of the 'pure film drama', gave him the opportunity to make

two films: Sei no kagayaki ('The glow of life') and Miyama no otome ('Maid of the

deepmountains', both 1918). These films were set in imaginary westernized

circumstances, avoiding the highly codified comportment of the actors employed in

traditional Japanese cinema, and manufacturing naturalism that was complete opposition

to the prevalent Japanese style. They were the first Japanese films actively, if very

naïvely, to adopt western concepts of art.

Slowly other film companies took up this trend, and by the early 1920s the traditional

form of Japanese cinema had become completely old-fashioned. The period between 1920

and the first half of 1923 (just before the Great Kanto Earthquake) witnessed a change of

form in Japanese cinema. The New School became established as modern drama, and the

Old School as the period drama. There was a transition from the traditional theatrical

form to the studio system, and film style, as well as the production process, began to

follow the western model. The earliest form of Japanese cinema, which avoided rapid

changes of images, used intertitles only for the chapters of a story, or used filmic images

for discrete segments of a stage play as seen in the chain drama, was obliged to change in

this period, even within the most conservative companies, like Nikkatsu. The company

resisted assimilating to the western form for a long time and attempted to preserve

tradition, but finally the audience's changing demands prompted change in company

policy.

In this short period, two ephemeral companies made some interesting films. One of the

two was Kokkatsu, which absorbed Tenkatsu in 1920, and gave Norimasa Kaeriyama the

opportunity to make films. This company not only produced period dramas directed by

Jiro Yoshino, but also began actively employing actresses in the place of oyama. It

allowed some directors to experiment with making realist films, such as Kantsubaki

('Winter camellia', Ryoha Hatanaka, 1921), or films which partially employed

expressionist settings, for example Reiko no wakare ('On the verge of spiritual light',

Kiyomatsu Hosoyama, 1922).

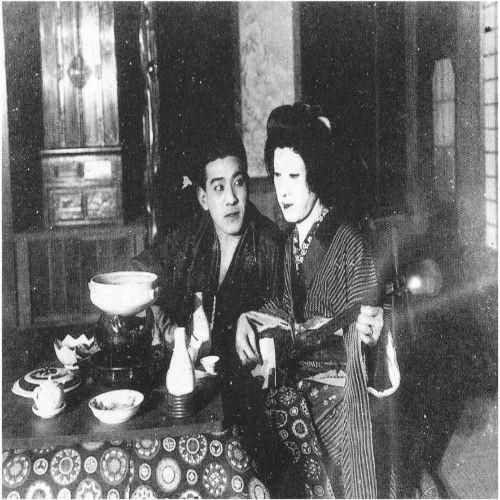

Eizo Tanaka's Kyoyo erimise ('Kyoka, the collar shop', 1922), one of the last Japanese

films to feature oyama (male actors in female roles)

The Taikatsu Company was established to produce intellectual films. This company did

not, unlike Nikkatsu and Kokkatsu, draw the audience in by making Old School sword-

play films with popular stars, and neither was the company interested in the already

codified form of New School films. Taikatsu's intention was to produce cinematic

Japanese films inspired by, but not directly imitating, European and American cinema.

For this purpose, the company invited Junichiro Tanizaki to be their adviser. Their first

production was The Amateur Club ( Kisaburo Kuri hara , 1920), in which elements of

American cinema -bathing beauties, chase scenes, slapstick-were adapted to Japanese

circumstances, attaining a visual dynamism absent from other traditional Japanese films

of the time. This was one of the first Americanized films produced in Japan, and its

director, Kurihara, went on to make Katsushika sunago ( 1921), Hinamatsuri no yoru

('The night of the dolls' festival', 1921), and Jyasei no in ('The lasciviousness of the viper',

1921) at Taikatsu, and expand this aesthetic.

The early 1920s also saw the establishment of Shochiku Kinema, a company which

relinquished archaic filmmaking from the outset, and introduced American formulas in

film direction. Shochiku used actresses who adopted facial expressions found in

American films in order to represent psychological complexity, and tried to render the

more natural movement of the everyday world. Shochiku built a studio in Kamata, Tokyo,

and immediately began to produce Americanized films under the advice of George

Chapman and Henry Kotani from Hollywood studios. The tendency to represent the naïve

imaginary world, as seen in the works of Kaeriyama, and a blatant desire to rebuff the

traditional Japanese style, were the hallmarks of the Shochiku films. The forthright

Americanism of the studio was decried by critics at first, but such criticism ceased in the

mid-1920s, when Japanese cinema as a whole assimilated a studio system based on the

model of the United States.

In 1920 such American methods in Japanese filmmaking would still have seemed strange

to the audiences, but the situation changed rapidly, and the system was transformed

virtually within a year. At Shochiku, Kaoru Osanai, the innovator of the theatre world,

turned to filmmaking, supervising the revolutionary Rojo no reikon ('Soul on the road',

Minoru Murata, 1921), the very apotheosis of the studio's desire to produce a new

Japanese aesthetic. In this film, plural stories were narrated in parallel, a new practice,

inspired by D. W. Griffith's Intolerance ( 1916). By this time even Nikkatsu, which had

been making the most traditional films, could not resist the current. In January 1921 the

company founded a special section for 'intellectual' film-making, dominated by the

director Eizo Tanaka, who made three films that year: Asahi sasu mae ('Before the

morning sun shines'), Shirayuri no kaori ('Scent of the white lily'), and Nagareyuku onna

('Woman in the stream'). These were, for Nikkatsu, attempts at innovation. They were

released in theatres that specialized in screening foreign films to an intellectual audience.

Their intertitles were written in both Japanese and English. The New School films

employed several benshi and the intertitles were traditionally felt to disturb the flow of

the filmic image. However, foreign films were narrated by a solitary benshi, so Nikkatsu

inserted bilingual intertitles into these 'intellectual' films to avoid the resistance of the

traditional film fans and to establish an affinity with the similarly titled foreign films.

Nevertheless, as the acting style in these films remained traditional, the attempts at

innovation were not wholly successful, especially in the face of competition from

Shochiku. Although Tanaka's films did feature actresses, in the main Nikkatsu, the last

film company to give up the oyama, continued to make films with them up until 1923.