The Oxford History of World Cinema (68 page)

Read The Oxford History of World Cinema Online

Authors: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

By the end of the decade a contradictory situation had arisen in Soviet cinema. The

montage cinema had reached a peak, or rather several peaks, since there were divergent

tendencies within it. On the one side was the theory of intellectual cinema, which

Eisenstein had begun to develop at the time when he was working on October (Oktyabr,

1927), and which took definitive shape in 1929 with his article 'The Fourth Dimension in

the Cinema' and came to exercise an important influence on the avantgarde. And on the

other side stood the so-called 'lyrical' or 'emotional' cinema, functioning through image-

symbols and typified by Dovzhenko's films Zvenigora ( 1927) and Arsenal ( 1929),

Nikolai Shengelai's Elisso ( 1928), and Yevgeni Chervyakov 's Girl from the Distant

River, My Son (Moi syn, 1928), and Golden Beak (Zolotoi klyuv). Trauberg recalls that,

under the influence of Eisenstein's article on the Fourth Dimension, he and Kozintsev

completely altered the montage principle of their film New Babylon (Novy Vavilon,

1929), abandoning 'linkage of the action' in plot development in favour of what Eisenstein

called the 'conflicting combination of overtones of the intellectual order'. They then saw

Pudovkin's freshly released The End of St Petersburg, which stood at the midway point

between the intellectual and emotional poles, and under its influence nearly remade the

film all over again.

This period, which was the high point of the development of the intellectual and lyrical-

symbolic montage cinema and the cinema of the implied plot, created at the same time a

parallel system in the commercial genre film -- notably in the work of Gardin ( The Poet

and the Tsar), Chardynin ( Behind the Monastery Wall), and Konstantin Eggert ( The

Bear's Wedding (Medviezhya svadba), 1926). But by the end of the decade articles began

to appear in the critical literature which censured both the innovators ('left-wing

deviation') and the traditionalists ('right-wing deviation'). In the spring of 1928 an All

Union Party conference on the cinema was called and the demand for 'a form which the

millions can understand' was put forward as the main aesthetic criterion in evaluating a

film. But the rejection of the commercial cinema, which furthermore was largely being

created by film-makers of the old school, bore witness to the fact that more than formal

questions were at stake. 'Purges' began in the cinema, and the images of the White Guard,

the kulak, the spy, or the White émigré wrecker who had insinuated himself into Soviet

Russia began to crop up in films with increasing frequency. Films like Protazanov's Yego

prizyv ('His call', 1925), Zhelyabuzhsky's No Entry to the City, Johanson's Na dalyokom

beregu ('On the far shore', 1927), and G. Stabova's Lesnoi cheloviek ('Forest man', 1928)

bear disturbing witness to this new trend. The increasingly powerful role of RAPP in

literature began to create a situation of ideological pressure of which the cinema too

became a target.

New Babylon (Novy Vavilon, 1929), Grigory Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg's epic story

of the Paris Commune

Besides the change in the political climate, the arrival of sound played a significant part in

the sequence of epochs in Soviet cinema. Already in 1928-9, before the new invention

had been introduced in the Soviet cinema, Soviet film-makers began to discuss its likely

implication. In 1928 Eisenstein, Pudovkin, and Alexandrov put forward the concept of

audio-visual counterpoint in a statement

'The Future of the Sound Film'. The engineers Shorin (Leningrad) and Tager ( Moscow)

were working at that time to create a sound-recording system for Soviet film studios. The

introduction of sound into the cinema becomes in a certain sense state policy. Pudovkin's

film Prostoi sluchai ('A simple case'), also known as Ochen'khorosho zhivyotsya ('Life is

very good', 1932), and Kozintsev and Trauberg's Odna ('Alone', 1931), conceived as

silent, were on orders from above 'adapted for sound', as a result of which they reached

the screen after a one- to two-year delay. Probably those in charge saw in the talking

picture one of the ways of bringing the cinema to the masses which the 1928 conference

had urged. And although for several more years, because of the absence of sound

projectors in country areas, silent films continued to be made alongside talkies (notably

Mikhail Romm's Boule de suif and Alex ander Medvedkin 's Happiness (Shchastie), both

of 1934), one can say that the silent film as an art form reached its zenith in Soviet cinema

by 1929, in which year it ceased to progress, yielding place to its successor.

Bibliography

Christie, Ian, and Taylor, Richard (eds.) ( 1988), The Film Factory.

Leyda, Jay ( 1960), Kino: A History of Russian and Soviet Film.

Piotrovsky, Adrian ( 1969), Teatr, Kino, Zhizn ('Theatre, cinema, life').

Istoriya sovietskogo kino v chetyryokh tomakh ('A history of the Soviet cinema in 4

volumes'), Vol. i: 1917-1931.

Lebedev, Nikolai ( 1965), Ocherk istorii kino SSSR. Nemoe kino (19181934) ('An outline

history of cinema in the USSR. Silent cinema').

Margolit, Yevgeny ( 1988), Sovietskoie kinoiskusstvo ('Soviet film art'). Moscow, 1988.

Ivan Mosjoukine (Ivan Ilich Mozzhukhin) (1889-1939)

Ivan Mosjoukine in the film he directed himself, Le Braiserardent ( 1923)

Born in Penza on 26 September 1889, the young Ivan Ilich Mozzhukhin went to law

school in Moscow for two years, but gave up his studies and left for Kiev, to pursue a

theatrical career. After two years touring the provinces, he returned to Moscow, where he

worked at several theatres including the Moscow Dramatic Theatre. He made his film

debut in 1911 in The Kreutzer Sonata, directed by Pyotr Chardynin, the first of many

films he was to make for the powerful Khanzhonkov Company. At first he was cast in a

variety of roles, from the comic in Brothers ( 1913), to the tragic hero of In the Hands of

Merciless Fate ( 1913). It was in 1914, while working with the director Yevgeny Bauer on

Life in Death ( 1914), that he developed what was to become his artistic trademark - a

steady, direct, tearfilled gaze turned full on the cinema audience. From this was born the

myth about the mystical power of Mozzhukhin's gaze. His role as a key dramatic and

melodramatic actor was confirmed in such films as Chardynin's Chrysanthemums ( 1914),

and Idols ( 1915), again with Bauer.

In 1915 he left Khanzhonkov and transferred to the Yermoliev studio. Here, under the

direction of Yakov Protazanov, the mystical element of his image was en hanced, while a

demonic edge entered into his richest characterizations - for example in The Queen of

Spades ( 1915) or Father Sergius ( 1917).

The ideas of the playwright A. Voznesensky helped Mozzhukhin to form a conception of

cinema which depended on the expressiveness of the actor's gaze, his gestures, his use of

pauses, and his ability to hypnotize his partner. Speech was to be avoided as much as

possible, and the ideal film would be devoid of all commentary and intertitles.

In 1919 Yermoliev and his troupe left Russia and set up in Paris. Mosjoukine under which

he was to become famous throughout Europe. His ideas on acting found reinforcement in

theories of cinema current in France at the time, most notably the idea of photogÉnie.

Towards the end of his Russian period an important new theme had emerged in his work;

the double or split personality. In the two-part epic Satan Triumphant ( 1917), directed by

Ch. Sabinsky, he played multiple roles, an experiment he repeated in Le Brasier ardent

( 1923), with himself as director. Doubles and doppelgängers surface many times in his

French films, most spectacularly in Feu Mathias Pascal ( 1925) adapted by Marcel

L'Herbier from a Pirandello story about a man believed dead who invents a new life for

himself.

Mosjoukine was also a poet, and in his poems he compares himself, as actor and as

émigré, to a werewolf, many sided and restless. From this sprang the figure of the eternal

wanderer ( Casanova, 1927) and the Tsar's courtier ( Michel Strogoff, 1926). But what

most preoccupied him during his French period was a constant wish to rid himself of the

'mystical' film star persona. He attempted this in various ways - by infantilizing and thus

caricaturing heroic roles, by a return to comedy, or by bringing opposing character types

together in one film. This conscious eclecticism was reinforced by his discovery of the

French avant-garde and of American cinema - notably Griffith, Chaplin, and Fairbanks.

His interest in America aroused, he moved there in 1927, appearing in just one film,

Edward Sloman's Surrender. Later than year he returned to Europe. In Germany he

rejoined some of his fellow émigrés, and himself played the role of the Russian émigrée

in two major films, Der weisse Teufel ( 1929) and Sergeant X ( 1931). However, as he

had always feared, speech in film proved to be a problem and in a foreign language even

more so. His last roles were few and of little consequence. On 17 January 1939 he died of

acute tuberculosis in a hospital for the poor.

NATALIA NUSSINOVA

SELECT FILMOGRAPHY

The Kreutzer Sonata ( 1911); Christmas Eve ( 1912); A Terrible Vengeance ( 1913); The

Sorrows of Sarah ( 1913); Satan Triumphant ( 1917); Little Ellie ( 1917); Father Sergius

( 1917); Le Brasier ardent (also dir.) ( 1923); Feu Mathias Pascal ( 1925); Michel Strogoff

( 1926); Casanova ( 1927); Surrender ( 1927); Der weisse Teufel ( 1929); Sergeant X

( 1931); Nitchevo ( 1936).

Sergei Eisenstein (1898-1948)

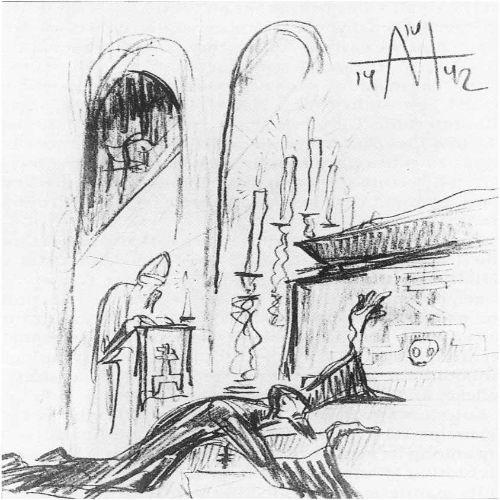

A drawing by Eisenstein for Ivan the Terrible ( 1944)

At age 25 Eisenstein was the enfant terrible of Soviet theatre; The Wiseman, his

irreverent, circus-style production of an Ostrovsky classic, marked a high point of

experimentation in the post-revolutionary stage. After two more productions Proletkult

invited Eisenstein to make a film. It became The Strike ( 1925), and Meyerhold's pupil

soon became the most famous Soviet film-maker. 'The cart dropped to pieces', he noted

some years later, 'and the driver dropped into cinema.'

Eisenstein brought his theatrical training into all his films. His version of Soviet typage

relied on the depsychologized. personifications he found in commedia dell'arte. His later

films unashamedly invoked the full resources of stylized lighting, costume, and sets.

Above all, Eisenstein's conception of expressive movement, exceeding norms of realism