The Other Slavery (34 page)

Authors: Andrés Reséndez

We do not know the ultimate fate of these women, but after having tangled with smallpox, they faced a second life-and-death struggle along the Gulf of Mexico coast in the form of two mosquito-borne killers: yellow fever and malaria. Stagnant water, warm temperatures, and a lush tropical environment make the port of Veracruz an ideal habitat for a multitude of insects, including the

Aedes aegypti

(transmitter of yellow fever) and

Anopheles

(transmitter of malaria) mosquitoes. Clouds of mosquitoes cover the swampy coastal areas around the port of Veracruz and are impossible to avoid, least of all in a dungeon holding Indians like San Juan de Ulúa. During the day, one can swat away a few mosquitoes. But at night, while asleep, one is completely at their mercy. Hundreds or even thousands of bites are not uncommon, and all it takes is one bite from an infected female mosquito of either species to get into trouble.

Of these two illnesses, yellow fever was easily the most lethal to a people lacking immunity, like these Indian prisoners from the deserts of northern Mexico and what is now the American Southwest. The yellow fever virus passes through the mosquito’s saliva into the bloodstream of

the human host and spreads to the liver, where it reproduces, causing chills, muscle pain, and high fevers after three to six days. The skin of the sufferer becomes noticeably yellow as a result of the damage to the liver, hence the illness’s name in English. In Spanish it is often referred to as

vómito negro,

or black vomit, because it also causes hemorrhages in the gastrointestinal tract, and the vomited blood is often dark red or black. Yellow fever outbreaks could easily cause mortality rates of more than fifty percent among people who had no prior exposure to

Aedes aegypti.

Although the fragmentary information about the colleras does not permit even a rough estimate of the mortality rates of Indian prisoners held in Veracruz or shipped to Cuba, the constant concern of Spanish officials about “malignant fevers” is a clear sign that yellow fever and malaria lurked in the background.

31

The colleras of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries show in tangible ways that epidemic disease did not spread evenly across the Americas. Indians living in the interior of North America seemed to have suffered comparatively less from epidemic disease than those inhabiting coastal regions or residing in large urban agglomerations. In the dry and sparsely populated regions of northern Mexico and the American Southwest, pathogens had a harder time spreading than in coastal areas, where tropical diseases reigned supreme, and in urban centers, where the “crowd diseases”—for example, smallpox and cholera—were common. There is little doubt that the colleras of the late eighteenth century were an ideal mechanism for infecting Indians from the north. By forcing them into close and even intimate contact with Spanish soldiers for a month or longer; parading them through towns and cities; compelling them to mingle with criminals and paupers in jails and hospices in the large cities of central Mexico; and finally marching them to the Gulf coast, thus exposing them to another suite of mosquito-borne diseases, the Spaniards made these Indians as vulnerable as possible to smallpox, yellow fever, and other deadly illnesses.

32

It is also likely that the colleras facilitated the spread of epidemic disease from south to north, as soldiers and drivers moved back and forth and Indian prisoners already exposed to pathogens in central and southern Mexico escaped and found their way back to their home

communities in the north. This is one of the most elusive, but tantalizing, aspects of the Indian drives of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. From 1775 to 1782, North America experienced a smallpox epidemic of continental proportions, from the Atlantic to the Pacific and from the Caribbean and southern Mexico to Canada, as has been documented by historian Elizabeth A. Fenn. The exact origin of this major outbreak is unknown. But sometime in 1779, it reached Mexico City. With its 130,000 inhabitants and its many jails, hospices, churches, schools, and other nodes of infection, the largest city in the Western Hemisphere offered a most auspicious environment for the spread of smallpox. When the first cases were reported in the late summer of 1779, the illness seemed eerily mild, but it gained strength during the fall. By late December, more than 44,000 Mexico City residents had come down with smallpox, and an estimated 18,000 had succumbed to the disease. Indians from northern Mexico must certainly have been affected. In 1778 no less than three different colleras, originating in Tamaulipas, Coahuila, and Chihuahua, had arrived in the city.

33

From Mexico City, the disease radiated out in all directions. Fenn looked at the burial records in various parishes, tracking the increasing number of deaths as the disease moved like a tidal wave from town to town. Although priests seldom indicated the cause of death, the skyrocketing number of burials leaves no doubt as to the reason. Smallpox’s relentless march north is easy to document. During the winter of 1780,

Variola

made dramatic inroads through much of central Mexico. By the late spring and early summer, it had reached the mining areas of Parral and Chihuahua. By the end of the year, it had spread all the way to New Mexico, as well as to the coast of Sinaloa and Sonora and to portions of Tamaulipas and Texas. And by the summer of 1781, it had reached the Comanchería. Of course, it is impossible to correlate specific Indian drives with the spread of this devastating epidemic. But it is remarkable that even in the midst of this outbreak, the colleras continued: one in 1780 and three more in 1781. These Indian drives, moving dozens of susceptible indigenous hosts and requiring soldiers to move back and forth between central and northern Mexico, would have been excellent carriers of the disease.

34

9

Contractions and Expansions

B

Y THE EARLY

nineteenth century, Indian slavery had nearly disappeared on the east coast of North America. In colonial times, the Carolinas had been a major Indian slaving ground; New Englanders had impressed rebellious Indians and shipped them to the Caribbean; and French colonists in eastern Canada had impressed thousands of Natives from the interior. During the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, however, the traffic of Natives was replaced almost completely by that of African slaves. Only a few vestiges of the old trade networks remained, notably in Florida. There Indian traditions of captivity harking all the way back to pre-Columbian times continued to function. But even these practices became redirected toward blacks. The Seminoles, for instance, took Africans as slaves. Not surprisingly, Americans living along the Eastern Seaboard lost any awareness of earlier forms of indigenous bondage. When they spoke or wrote about slavery in the nineteenth century, they invariably meant African slavery.

1

Yet Indian slavery continued to thrive in the West and even expanded as traffickers capitalized on some of the momentous changes of the early 1800s. Mexico’s struggle for independence from Spain (1810–1821) was probably the most important catalyst of this expansion. Ironically, the leaders of the insurgency called for “the abolition of slavery forever” and the elimination of “all distinctions of caste so we shall all be equal.” And

they made good on their promises. The newly independent government granted citizenship rights to all Indians living in Mexico and abolished slavery in 1829. However, presaging what would happen later in the century in the United States, with the Civil War and Emancipation Proclamation, these measures, far from ending Indian slavery, paved the way for its transformation and further expansion.

2

More immediately, Mexico’s eleven-year struggle spelled economic disaster. Much of the fighting took place in the mining districts, prompting workers to abandon the silver mines. With no workers there to pump out the water that accumulated as a result of rainstorms and underground seepage, the mines became completely flooded, and these extraordinary engines of growth became mere holes in the ground. It would take half a century for Mexico’s mineral exports to return to late-colonial levels. In the meantime, the economic decline led to a breakdown of most frontier controls. The number of soldiers posted in northern Mexico dwindled, presidios were abandoned, and the region became vulnerable to Indian attacks. The Comanches, who had been expanding for a century, and the Apaches, who knew the terrain extremely well, pushed deep into Mexico, descending on haciendas and abandoned mines and capturing women and children.

3

The Comanches in Mexico

The Comanche expansion into Mexico started suddenly and coincided with the initial turmoil of independence. Few testimonies are as eloquent as that of landowner and politician Miguel Ramos Arizpe, who had grown up in the state of Coahuila (just south of Texas) during the halcyon days of the Spanish silver boom. A line of presidios running along the Rio Grande had afforded his home state a measure of security that had made it wealthier and better populated than Texas. Though not impassable, these garrisons presented a real obstacle to Indian raiding. As Ramos Arizpe explained, “The various tribes of the Comanchería lived in the enormous plains and sierras between Texas and New Mexico north of the line of presidios . . . and they knew very well that the

principal access into the interior provinces of Coahuila, Nuevo León, and Tamaulipas was closed off to them.”

4

Yet the struggle for independence opened the floodgates. “We observed that the heathen Indians who during entire centuries had taken just a handful of children as captives,” Ramos Arizpe recounted, “in the short years between 1816 and 1821 took more than two thousand captives of all kinds, genders, and ages, and killed as many people or more in Coahuila, Nuevo León, and Tamaulipas.” He was personally affected by the upsurge in Comanche activity. Ramos Arizpe owned eight hundred square leagues (more than four million acres) of well-irrigated land on the Rio Grande. But he could neither protect nor develop his vast domain because it lay in the path of Comanche expansion. His property included the ruins of the old presidio of Agua Verde, a poignant reminder of Mexico’s military retreat.

5

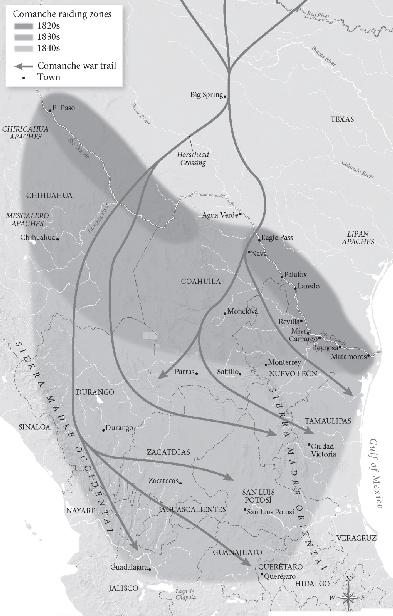

The Comanches would go on to wage a ruinous war in northern Mexico in the 1830s and 1840s, as historian Brian DeLay has shown. They mounted more than forty raids into Mexico during this period—more than two per year on average. Half of them were actually large-scale military operations involving up to a thousand warriors. Considering that the total Comanche population may have been between ten and twelve thousand, and assuming that there was one warrior for every five Comanches, a “raid” of one thousand men amounted to half the Comanche fighting force, as DeLay notes. Just as impressive was their geographic scope. They came to engulf much of Chihuahua, Durango, Coahuila, and Nuevo León, as well as half of Tamaulipas, reaching as far south as Zacatecas, San Luis Potosí, and Querétaro, not far from Mexico City.

6

These raiding campaigns were not intended solely or even primarily to take captives. Later interviews with Comanches make clear that the acquisition of horses was the principal objective. Warriors competed with one another over the number of mounts they possessed and sought to procure as many horses as they could by any means. Chief Esakeep expressed great pride in his four sons because they could steal more horses than the other young men in the tribe. In fact, horses were an absolute necessity for any long-distance raid. To conduct these campaigns, Comanches needed to travel hundreds of miles. And once deep in Mexico,

they needed to retreat swiftly, carrying captives and loot. Having sufficient animals and the ability to change to fresh mounts was critical.

7

Procuring goods was another major goal of these incursions. The Comanchería was a trading center that absorbed a variety of commodities that were consumed internally or traded to other groups. Clothes and textiles were excellent forms of plunder—lightweight, easy to transport, and always in high demand. Raiders went through the trouble of removing the clothes of their prisoners before killing them and taking shirts and pants from corpses during a raid. They also paid special attention to metal objects. Knives, lances, and firearms were obviously important. But Comanche raiders also took latches, nails, bolts, and other metal objects that could be transformed into valuable tools with a forge.

8

Even though taking captives was not the primary purpose of these raids, Comanches took hundreds of them in the 1830s–1850s. Each could fetch anywhere between 50 and as much as 1,000 pesos (or dollars, for in that golden era, there was parity between the two currencies). In other words, by the middle of the nineteenth century, a captive was far more valuable than a horse or a mare. A group of Apaches traveling near the Pecos River in February 1850, for example, exchanged a ten-year-old boy from Saltillo for “one mare, one rifle, one pair of drawers, thirty small packages of powder, some bullets, and one buffalo robe.” Around the same time, a twelve-year-old boy from Mexico was traded east of the Rio Grande somewhere in New Mexico for “corn and tobacco, one knife, one shirt, one mule, one small package of powder, and a few balls.” The Comanches and Apaches must have developed a good sense of the value and desirability of each type of captive, which varied greatly depending on the circumstances. Anglo-Americans and well-off Hispanics (people of Mexican origin living in what is now the American Southwest) were especially attractive because they could be held for ransom; women were more valuable than men; youngsters (but not babies) were preferred over older folks; boys were preferred over girls; and adult males were generally not worth the trouble except in unusual circumstances.

9