The Other Slavery (31 page)

Authors: Andrés Reséndez

In hindsight it is clear that the introduction of horses and firearms precipitated another cycle of enslavement in North America. In the sixteenth and much of the seventeenth centuries, Europeans had maintained their technological superiority, which they had used to enslave tens of thousands of Native Americans. But once the genie was out of the bottle, their initial advantages vanished. By the mid- to late seventeenth century, the Spaniards were able to take fewer and fewer captives as Native Americans rose to the challenge of European colonialism. Some Indian societies negotiated accommodations with the newcomers. Others fled to inaccessible areas. And yet others transformed themselves into powerful forces by taking advantage of the very technologies and markets created by Europeans. All of them became active participants in the other slavery, thus making the system harder to control than ever. In absolute numbers, the other slavery declined during the eighteenth century, but it also evolved and became more deeply entrenched. And it was not just Native Americans who became more adept at taking slaves. In response to this newfound Indian power, Spanish colonists pioneered new practices of enslavement, to which we turn next.

8

Missions, Presidios, and Slaves

I

N RECENT YEARS

, historians have painted a fascinating new picture of Indian power in North America. They have shown that many Indian societies retained a great deal of control in their “native grounds” and at times acted as “militaristic slaving societies,” even full-scale “empires.” But with so much emphasis on Native control, it is easy to miss the point that Europeans also adapted to the new circumstances. Just as the Comanches and Utes expanded their respective ranges in the eighteenth century, the Spaniards bolstered their religious, military, and demographic presence in northern Mexico. A fantastic silver boom allowed them to dig in their heels. Mexico’s production of silver bullion increased by an astounding four hundred percent—from 1,272,680 kilograms (1,403 tons) of fine silver in 1701–1710 to 4,878,510 (5,378 tons) in 1801–1810—making Mexico the world’s leading producer of the white metal. For much of that century, Mexico mined more than half of all the silver extracted in the world. To keep the supply flowing, the crown invested some of the proceeds in military garrisons. In effect, Spain militarized Mexico’s northern frontier.

1

The mission was Spain’s first frontier institution. In the early years of colonization, friars boldly ventured into unsettled areas, established contact with Indians, and acted as diplomats, spies, and agents of the crown. In a field-defining essay published almost one hundred years

ago, Berkeley historian Herbert E. Bolton argued that just as English backwoods settlers had “driven back the Indian step by step” and French fur traders had “brought the savage tribes into friendly relations with the French government,” the missions had played the leading role on the Spanish frontier, teaching millions of Indians the language of Cervantes, introducing them to the mysteries of Christianity, exposing them to every conceivable European plant and animal, and giving them the rudiments of European crafts and agriculture.

2

Yet for all of these “accomplishments” (now we know that Bolton’s approach was decidedly Eurocentric), missions proved inadequate to secure the unsettled frontier. Working alone or in pairs, friars simply lacked the means to control territory or enforce a European-style regime. Missionaries depended on Native leaders to decide whether it was to their peoples’ advantage to live within a mission. In many instances, Indians found that life under the mission bell was too regimented for them and ultimately abandoned their missions. As the friars were powerless to retrieve absconding Indians, they had to rely on Spanish soldiers to help them carry out their work of religious instruction. And if the missions’ vulnerabilities were noticeable even in cases in which Indians were initially cooperative, they were blatantly obvious when missionaries were dealing with powerful groups such as the Utes, Comanches, and Apaches, who refused to allow missions into their territories. These nations wanted nothing to do with the meddlesome robed men bent on monogamous marriage, a sedentary way of life, and other strictures, and there was nothing the missionaries could do about it.

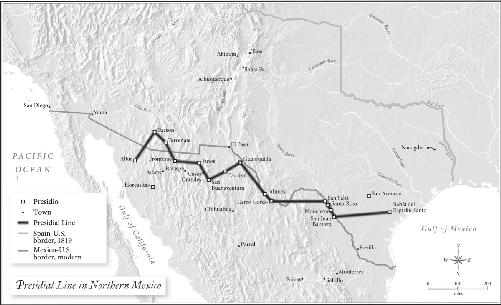

3

Spanish officials thus opted for a more forceful means to protect Mexico’s silver districts. They ordered the establishment of military garrisons all along the frontier and deployed more soldiers. There certainly had been militias and presidios before, but the shift in emphasis was clear. Although missionaries continued their work throughout the eighteenth century and even expanded into new areas such as Alta California, the military came to play a more prominent role. In 1701 northern Mexico had 15 companies and a total of 562 soldiers. By 1764 the number of units had more than doubled to 23 companies and 13 squads, and the total troop strength was 1,271. To keep southward-moving Indians such

as the Apaches and Comanches in check, Spanish policymakers also decided to set up a line of presidios stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific. This presidial line was very close to today’s international border between Mexico and the United States. Of course, the current border took shape only in the middle of the nineteenth century, in the aftermath of the U.S.-Mexican War. But considering that a border is merely the outer rim of an area over which a nation exercises control, this line of presidios overlaid on Indian domains constituted Mexico’s northernmost edge of effective control and therefore its border in a more profound way.

4

For the Indians, the presence of missions and presidios represented both opportunity and danger. Indians preferred to engage these outposts intermittently and on their own terms—perhaps to procure goods or food or even to gain temporary employment, but nothing more. However, their very existence made life risky for Natives living in the vicinity, as they increased the Indians’ vulnerability to European labor demands. This was especially true for small nomadic or seminomadic bands that had little else to offer but their labor. The alternatives were stark for them. They could either take to inaccessible areas beyond the pale of Spanish control or strike a bargain with the Devil, so to speak, by joining a mission or presidio while negotiating the best possible arrangement.

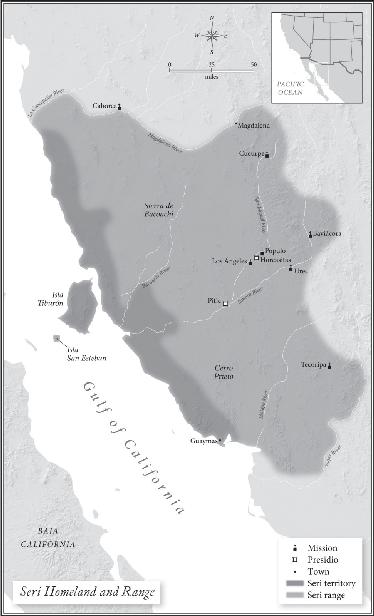

Consider the choices available to the Seri Indians. The Seris had been living on the coast of Sonora with little outside interference for centuries, if not millennia. Their language is unrelated to any others in the region—an “isolate” in the parlance of linguists. Seri mitochondrial DNA exhibits a distribution of markers that is extremely rare among the Indians of Mexico or the Southwest (with a high percentage of the haplogroup C founding lineage), and their Y-chromosome DNA reveals low levels of diversity, also suggesting isolation. To be sure, the Seris traded with their neighbors, as the archaeological and historical records make clear. But they could always retreat into their homeland, which was so inhospitable that no other groups wanted to have it. Anyone who has seen this coastal desert would readily appreciate the tremendous difficulty of eking out a living there. Agriculture was

entirely out of the question. The Seris—or Comcáac, as they call themselves—were true nomads, extremely attuned to a variety of local resources. They regularly used as many as 75 different plants and had names for an astounding 350 to 400 of them, as ethnobotanists have been able to determine. The Seris also turned to the bounty of the sea. On flimsy boats made from reeds, they ventured into the Sea of Cortez to hunt turtles—even during the winter months when the animals lay half-buried on the sea floor—and to gather eelgrass when the shoots from the submerged plants broke off and floated to the surface in April. The Seris dried the seeds, ground them, and made a gruel, which they ate with turtle fat or honey. This is the only documented instance of a human population relying on a marine seed plant as a major food source.

5

Only toward the end of the seventeenth century did the Jesuits begin missionizing the Seris. Father Adam Gilg, a native from what is now the Czech Republic, was one of them. In 1688 he journeyed to Sonora to take up his post at the mission of Santa María del Pópulo. The site was nothing but a crude shrine, a few Seri families living in branch huts, and scattered fields irrigated by the San Miguel River. The name Santa María del Pópulo—one shared with an opulent church in Rome—was certainly incongruous. But the most disappointing circumstance for a committed priest like Father Gilg was that the mission lay well outside the Seri homeland. Because the coast would have been too harsh an environment to sustain a community based on agriculture, Pópulo was seventy-five miles inland, merely a beachhead on the edge of the Seri world.

Still, Father Gilg took these drawbacks in stride. This German-speaking Jesuit quickly discovered that the Seri language would be a major obstacle to his evangelizing efforts, yet he claimed that their speech reminded him of German. Gilg was taken aback by the Seris’ nakedness, but he found comfort in the fact that their lack of clothes did not seem to cause lewdness or promiscuity. “I have not seen a single unmarried woman sin,” he wrote. He even found the Seris’ halting attempts at wearing clothes amusing: “Some wear only shirts. Others wear only pants. And yet others wear their pants wrapped around the chest . . . and all of these articles pass from hand to hand because the Seris engage in a

betting game and pay each other with clothes.” Father Gilg was generally content with his flock, calling them “my Seris” when he wrote to his brethren in Europe. “This is not the kind of mission where one runs the risk of becoming martyrized,” he proclaimed reassuringly, “but not everyone can come here as the work requires missionaries who are able to withstand discomfort and want of everything.”

6

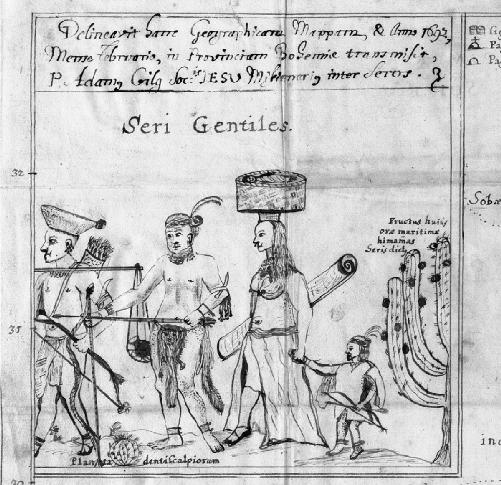

Father Adam Gilg drew this sketch of Seri Indians in February 1692. The woman is carrying a basket on her head and a mat under her arm. The men are armed with bows and arrows, as well as knives protruding from their armbands. All the Indians are adorned with necklaces, nose rings, and feathers.

Father Gilg’s hopeful letters fit with our image of missions as privileged sites of Indian-European interaction. Like many other idealizations, this one is based on a modicum of truth. The Seris did receive the Jesuit missionaries peacefully, but one important reason was that the padres gave away food liberally. As one missionary noted, it was necessary to win over the Seris “by their mouths.” By all accounts, the robed men delivered. The river valleys of central Sonora were narrow but possessed surprisingly fertile land. By building canals, dams, and wells, using manure as fertilizer, applying European plowing methods, and rotating crops, missionaries were able to get sizeable surpluses.

7