The Operators: The Wild and Terrifying Inside Story of America’s War in Afghanistan (19 page)

Read The Operators: The Wild and Terrifying Inside Story of America’s War in Afghanistan Online

Authors: Michael Hastings

The political pressure on Obama to act builds. There’s an outcry from the press that he’s dragging his feet. The White House responds by saying they are taking their time, they are making a mature policy decision—something that Bush never did in Iraq and Lyndon Johnson never did in Vietnam. The White House fears Petraeus could resign in protest if Obama doesn’t commit to the troop surge. Press reports quote other unnamed military officials saying McChrystal will resign, too. McCain and Senator Joseph Lieberman start to lobby for Obama to send more troops. Jones starts to come around to the idea of sending more troops—he doesn’t want “to sandbag his old colleagues,” he thinks. Gates claims he struggled to reach his decision about sending more troops—he waits to endorse whatever decision best defends the interests of his generals. Another insider tells Wolffe: “The Afghan review went in the direction of Gates’s position.”

At the ninth meeting, on November 23, Obama is given a plan that he thinks is an improvement. Not, he thinks, the Biden plan, and not the McChrystal plan. The generals want forty thousand troops to surge over twenty-one months. In this plan, the forty thousand troops would surge over nine months. A “significant number of troops” would begin to come home by July 2011—with the caveat that the plan is based on “conditions on the ground,” a stipulation Gates and Mullen insist on. On November 26, the White House staffers work on an eight-page single-spaced consensus memo to fashion a policy, according to Alter. On November 29, Obama and Biden speak to the top military brass alone—walking into the meeting, Obama assures Biden that the July 2011 deadline would not be “countermanded” by the military.

In the end, Obama attempts to split the difference—he gives the military the troops they want, but tells them they need to leave sooner than they’d like to. He thinks this asserts his authority and proves that he hasn’t caved. The Pentagon reads it another way: He gave us what we

wanted, and he dragged his feet for months, which confirms their suspicions that he isn’t truly committed to the war.

Obama insists that we won’t embark on a decade-long nation-building campaign. That troops need to start coming home sooner rather than later. Otherwise, he fears he’ll lose his liberal base. Within days of the policy announcement, Gates, Clinton, and others at the Pentagon make statements that describe what sounds like a decade-long nation-building campaign.

Obama gives McChrystal what he wants, warning him over a VTC: “Do not occupy what you cannot transfer.” Sure. McChrystal tells me the review is “painful,” and he calls the politics behind it “foolishness.” He describes the force of the opposition as “wicked.” McChrystal tells me things start to get better for him once Obama “took control of the process” and “stopped listening to his political advisors.” In other words, Obama starts to do well once he starts to do what McChrystal wants him to do. The White House, though, thinks it has the upper hand, as one advisor says about Obama’s attitude: “I’m president. I don’t give a shit what they say. I’m drawing down those troops.”

THE STRATEGY

APRIL 21, 2010, BERLIN

On the mezzanine level of the Ritz-Carlton, twenty German military and foreign policy experts gathered in a conference room to listen to McChrystal speak. The goal of the meeting was to shape the views of the country’s “opinion makers.” McChrystal believed he had a better chance of getting them on his side if he could look them in the eye.

“Let me start by introducing myself. I’m Stan McChrystal. I command ISAF right now,” he said. “We arrived in Berlin last night after a fourteen-hour bus ride from Paris. We got lost for the last hour or so. We’re a little bit like a rock band, except with no talent.”

The experts laughed.

“Afghanistan is so confusing that even the Afghans don’t understand Afghanistan,” McChrystal said. “If you think about Afghanistan—”

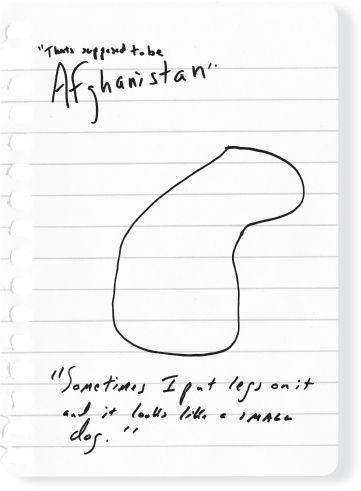

McChrystal turned to four whiteboards set up for the conference. He drew Afghanistan.

“That’s supposed to be Afghanistan. Sometimes I put legs on it and it’s a small dog.”

I made copies of his sketches in my notebook, adding a few notes of my own.

He summarized, layering fact upon fact. Afghanistan has a population of thirty million. Historically it was a buffer state between great powers. There is one major road in the country. There are Pashtuns in the south, Tajiks, Hazaras, and Uzbeks in the north. It’s really more complicated than that, he says; in the twenties, the Pashtuns were relocated everywhere, so there are Pashtun populations mixed in.

“You can get confused real quick,” he said. A single person can identify as a Popalzai, a Durrani, a Kandahari, and an Afghan. Ethnic divides weren’t that big a deal until after the Soviets left in 1989. There’s a tremendous

cultural aversion to change. It’s not Islam, it’s not Taliban, it’s not Al-Qaeda. It’s Afghan culture. It’s cultural conservatism, he explained.

“So when we come in and start talking about women’s rights,” he said diplomatically, “they might not see it that way.”

The Soviets came, McChrystal said, and “they did a lot of things right. The Soviets did a lot of things correctly.” They modernized. They created an Afghan army and police force. They built roads. They promoted a strong central government. They promoted education for both boys and girls. They did things “differently,” too, he says. He means the Soviets carpet bombed and killed an “unimaginable” number of people. Death toll: 1.5 million. Then the nineties: The warlords took over. The warlords fought one another, killing tens of thousands. Then the Taliban fought the warlords, killing tens of thousands more. The warlords lost. Then, in 2001, the Americans came in. The Taliban went out. The warlords, “those same characters,” McChrystal said, are now back in power.

The economy is torn to pieces. Seventy percent less irrigation than Afghanistan had in 1975. Other facts: GDP is around $15.6 billion, with close to 97 percent coming from foreign aid. That’s not sustainable. The literacy rate is about 28 percent. It’s a culture made up of fighters, McChrystal said, an entire class of professional fighters who know only how to fight. We want to get them to put their arms down and take up other, peaceful jobs. But there are no jobs. Ergo, we have to create new jobs and get them to put their weapons down.

Corruption: $3 billion has flown out of Kabul Airport, in cash, over the last three years. The corruption is at a level that “Afghans have never seen,” McChrystal said. It is the fifth poorest country in the world.

The country has been at war for thirty-one years. The average life span of an Afghan is forty-five years. Sixty-eight percent of the population is under twenty-five years old. No one remembers what peace looks like, McChrystal said. Karzai thinks he does, said McChrystal—when Karzai talked to McChrystal, he often got nostalgic about how things were when he was a kid. So the goal is to try to re-create Afghanistan in the 1970s:

Forget the two coups and the Soviet invasion. To find the “brief period of solace,” as it’s been described, between the fifties and the seventies, when American backpackers and hippies traveled safely through the country. The goal is to turn the clock back to 1979.

“The people are tired, they’re frustrated. They had great expectations. Now, their expectations might have been unrealistic. They don’t see what they were promised. They don’t have confidence. People don’t know the future. They don’t have confidence the government will win. They don’t have confidence that the international community will stay. They fear the Taliban. The insurgency is extensive around the country.”

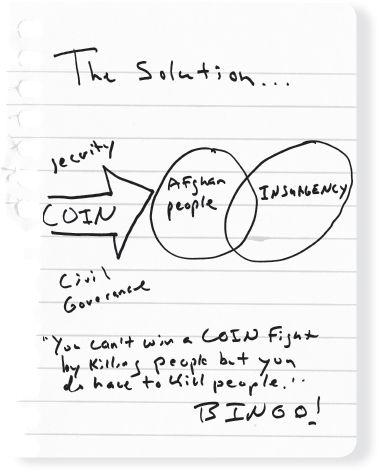

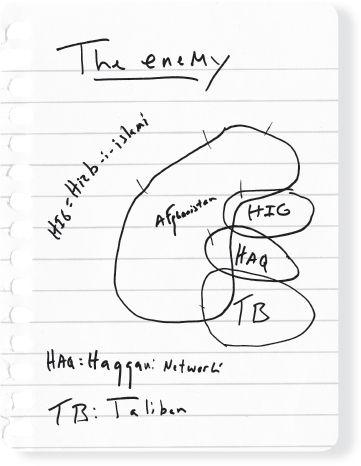

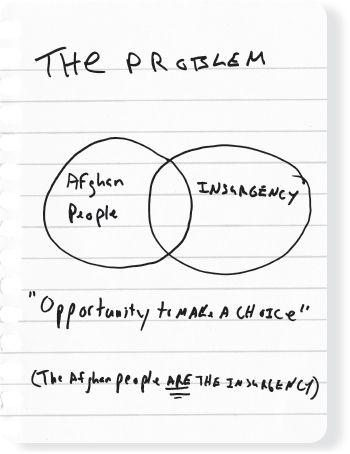

McChrystal drew another diagram.

Insurgents are Afghans. What is essential for success is not to kill the insurgents, because they are the Afghan people. If you kill the insurgency, you kill the Afghan people you came to protect, and there’s nobody left to win over.

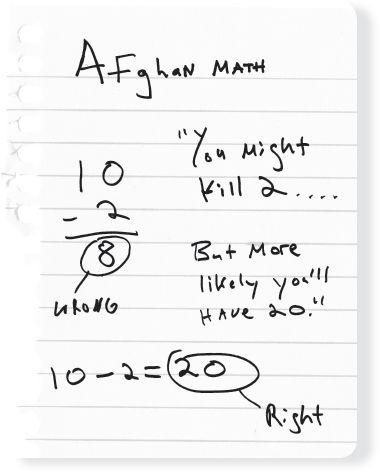

If you kill two out of ten insurgents, you don’t end up with eight insurgents. You might end up multiplying the number of fighters aligned against you. McChrystal called it “insurgent math.”

If you kill two, he said, “more likely, you’re going to have something like twenty. Those two that were killed, their relatives don’t understand that they’re doing bad things. Okay, [they think,] a foreigner killed my brother, I got to fight them.”

However, you have to kill sometimes, too, he noted.

“You can’t win a COIN by killing people,” McChrystal said. “But you do have to kill people when you have no other choice.”

He added an arrow to his whiteboard diagram. This was the strategy.

“If you push the insurgents like a rat in the corner, they will fight,” he said. “We all would. The way out is to come back into society. With honor. In five years or ten years, the problem will be right back again. A lot of people in Afghanistan have blood on their hands. If we spend our time worrying about that, there won’t be anyone to have peace talks with.”