The Operators: The Wild and Terrifying Inside Story of America’s War in Afghanistan (22 page)

Read The Operators: The Wild and Terrifying Inside Story of America’s War in Afghanistan Online

Authors: Michael Hastings

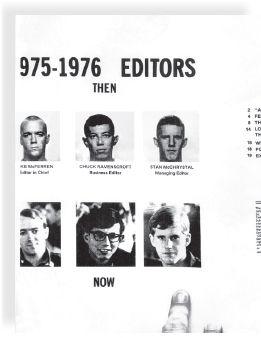

The Pointer’

s editorial board,

featuring McFerren and McChrystal

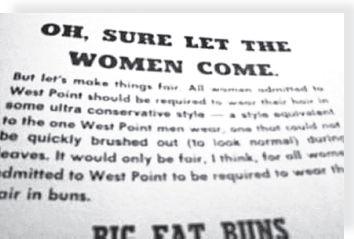

An editorial in The Pointer from the class of ’76

McChrystal is a dissident ringleader on campus. One classmate, who asked not to be named, describes finding McChrystal passed out in the shower after he drank a case of beer he’d hidden under the sink. He views the tactical officers, sort of like glorified residential advisors at West Point, as the enemy.

The troublemaking puts a serious crimp on his social life: In 1973 he starts to date Annie, whom he’d met at Fort Hood, Texas, but usually when she visits she barely gets a chance to see him. “I’d come visit and I’d end up spending most of my time in the library, while Stan was in the Area,” she tells me. McChrystal’s roommate, Jake McFerren, remembers having to keep Annie company in the library while Stan marched away his Saturday afternoons. “I remember going down to the Area, all the cadets were marching one way, back and forth. Stan sees me and Annie, and he breaks away, marches completely perpendicular to the formation, comes up and says, ‘This is bullshit.’ ”

McChrystal’s most notorious achievement—immortalized in a description underneath his yearbook photo—is the raid on Grant Hall, a gray stone building that was used for social engagements, a place for females visiting the all-male school to hang out.

McChrystal and five others borrow old weapons from the campus

museum, including a French MAT-49 submachine gun and dummy hand grenades made from socks. At 2215 hours, dressed in full commando gear and with painted faces, they storm Grant Hall. The main intent, says Barno (who didn’t participate in the raid) was to “create chaos.” McChrystal writes a satirical piece about his experience for

The Pointer

, the West Point literary magazine where he serves as managing editor. He describes the scene: “We moved swiftly to the… heavy brown doorway. Our hearts beating wildly… there were five of them blissfully unaware of the anger which lurked so near.… [L]ed by the sergeant, we burst out firing rapidly, dashed down the ramp, the light of Grant Hall cast a pallid glow on all of us. The rest is history.” A postscript to the story, which is accompanied by a cartoon of the raid with a soldier sneaking up on a busty coed and a photo of the five cadets in commando gear, says: “Delinquency: Extremely poor judgment, i.e. horse play with weapons in public at 2215 hours, frightening female visitors, and causing MP’s to be summoned 10 May 1974.” McChrystal headlined the article: “Where Goats Dare.”

McChrystal the Goat. The Goat is the name for the cadet who graduates last in the class. There are famous Goats—like George Armstrong Custer and George E. Pickett. The Goat excels in “mischief,” as one historian puts it, in fraternization, in extracurricular escapades along Flirtation Walk down by the Hudson. There is a two-century-long tradition of Goatism. Custer graduates last—726 demerit points!—yet is known as one of the most “dynamic” commanders in the Civil War. He becomes the Union’s youngest general. He earns his place in history, though, eleven years after the Civil War ends: His career spectacularly flames out in the massacre at

Little Bighorn, a misstep in the U.S. government’s campaign to wipe out America’s native population. Other Goats went on to win silver stars, great victories, and rise to the highest ranks. It is General Dwight D. Eisenhower who will later say, “If anybody recognized greatness in me at West Point, he surely kept it to himself.”

Part of a photo spread

from The Pointer

McChrystal embodies the Goat ethos, though he’s far from last in the class. McChrystal ranks 298 out of a class of 855, according to an official at West Point, a serious underachievement for a man widely regarded as brilliant. This puts him in the league with Sherman and Grant and Eisenhower and Patton—not quite scholars, but destined for history. His more compelling work is his writing, the seven short stories he produces for

The Pointer

. They are works of fiction and satire, which read like a cross between

The Naked and the Dead

–like war fiction and the amusingly subversive writings of a college student. The stories reveal a creative imagination that is obsessed with war, conflict, terrorism, and bucking authority.

One story, written in November 1975, titled “Brinkman’s Note,” is a piece of suspense fiction. The main character, an unnamed narrator, first appears to be trying to stop a plot to assassinate the president. It turns out, however, that the narrator himself is the assassin. He’s able to infiltrate the White House. “I had coordinated these plans routinely the day before with another member of the president’s staff, and everything was set. The main door to the plant opened. The president strode in smiling. From the right coat pocket of the raincoat I carried, I slowly drew forth my .32 caliber pistol. In Brinkman’s failure, I had succeeded.”

Other stories eerily foreshadow the issues he’d have to deal with thirty years later in Afghanistan and Iraq, including the difficulties training the Afghan security forces and the civilian casualties during insurgencies. In a story called “The Journal of Captain Litton,” the main character is a British officer in the Middle East who writes, “commanding these North Africans is a noxious prospect at best… I’m hopeful that once they are out and moving amongst the enemy troops they will steady somewhat and

we will have reasonable chance of success.” The story hinges on the captain’s aide, an Arab named Abu, who eventually betrays all of the captain’s secrets to the enemy. Another story, “In the Line of Duty,” also set in the Middle East, is about a unit of Americans that accidentally opens fire on a local boy. With Vietnam looming in the backdrop, McChrystal the cadet confronted the issues of getting dragged into an open-ended counterinsurgency in a foreign land. His fictional character, a young lieutenant named Gewissen, would oppose a policy that the real McChrystal, later as a general, would have to embrace. “The troops, on constant alert for expected guerilla activity, had apparently mistaken the boy for a terrorist approaching the wire and had opened fire with a .50 caliber machine,” the story reads. Gewissen visits the scene of the incident and the following exchange with his commander occurs:

“I was told what happened, LT, don’t worry too much about it and tell the guard he can rest easy, too. We’ll put in a report that it was strictly in the line of duty. After all, what can the country expect when they put a nineteen-year-old kid over here on such an important mission?”

“Duty sir? Just what the hell is our duty? Wouldn’t you say we had a duty to that kid?”

Harris hardened, his voice growing colder. “Your duty is to the country, LT.”

“Which country, sir, this one or the one that sent us?” Gewissen was shouting now. “What about our duty to ourselves?”

One of McChrystal’s last pieces for

The Pointer

best gets at the psyche of the young cadet—chafing at bureaucracy, a dry sense of humor, and the willingness to flip the giant bird to his superiors. It’s about a student who sneaks into the registrar’s office to destroy Honeywell 635, a computer that has kept track of all the cadet’s “1,672 demerit hours in two months” and his poor academic performance. “The bombs are in place

and in minutes vengeance will be mine,” the story opens. “At first I attributed my constant bad fortune to some sadistic captain in the tactical department who, probably for some very good reason, bore a grudge against the family. Later, I thought that the CIA, FBI, SLA, or PTA might have sent a killer agent out to cause my slow, painful death, and at one point I even started attending chapel three times a day to cover all possibilities.”

“THE JERK IN GREEN”

APRIL 22, 2010, BERLIN

The next morning, I checked out the local papers to see the kind of coverage they gave McChrystal’s visit. He was on the front page of the three major German dailies. I bought copies of all three newspapers from the newsstand in the lobby. I headed up to the ops center on the ninth floor, the papers folded under my arm.

Charlie, Jake, and Admiral Smith were in the room. They were discussing McChrystal’s next speech.

“You’re going to talk about Marja, so that’s a major military operation. Obviously you have to lead toward Kandahar,” Jake said. “I like him saying it’s already going on. It’s not going to be D-Day, not a big assault. He used the term yesterday. It’s a

process

.”

The Marja offensive had started two months earlier, dispatching some ten thousand NATO soldiers and five thousand Afghan security forces to regain control over a town of about fifty thousand Afghans. Marja was located in Helmand province—the very place McChrystal had been concerned about committing forces to when he took over a year earlier. But now McChrystal had hyped it as the most important battle to date. It

had not gone well. McChrystal claimed that expectations for a clean and neat resolution were unrealistic. There were also no results to show. To deflect the criticism, the military used a variety of phrases to indicate the distinct lack of resolution in counterinsurgency operations—“rising tide of security” was one of them, “process” another. What was happening in Marja didn’t bode well for the next major offensive planned for Kandahar. Marja was supposed to be a “proof of concept,” as military officials put it, for Kandahar, and the concept looked like a failure.

While the team worked on the speech, they continued to game-plan a way back to Kabul. There was a NATO conference for foreign ministers in Tallinn, Estonia. NATO and State Department officials had suggested McChrystal put in an appearance there. Charlie tried to figure out why.

“They’re fucked up,” Charlie said. “They want him to go talk to the foreign ministers, but they don’t know if the foreign ministers are going to be there?” Charlie shook his head. “They’re fucked up,” he said again.

McChrystal walked in the room. “Hey,” he said.

“Sir.”

“This is our recommendation for the five-to-seven-minute intervention,” Jake said. (Intervention: what NATO ministers call speeches.)

Admiral Smith handed him an outline of notes. They wanted McChrystal to focus on “the training mission,” as it sounded less like “war.” They suggested he use phrases like “mentoring the Afghans.” Any questions about Kandahar should also be spun back to the larger point about the training mission, his advisors said.

“Five to seven minutes?” McChrystal said, skeptically, after looking over the speech.

“Is it more?”

“Oh, yeah.”

Dave sketched possible travel scenarios out on a whiteboard.

“Hey, Mike, how are you this morning?” McChrystal asked.

“Great, sir,” I said. “You see the papers?”