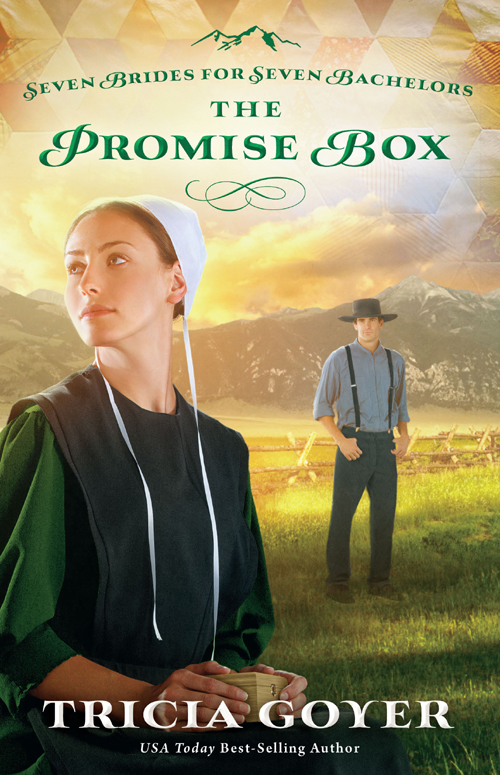

The Promise Box

Authors: Tricia Goyer

HE

P

ROMISE

B

OX

TRICIA GOYER

Dedicated to Linda Martin

Your handwritten notes through the years have been a special

treasure! Thank you for your love and encouragement, Mom

.

In returning and rest shall ye be saved;

in quietness and in confidence [trust] shall be your strength.

~I

SAIAH

30:15

1

L

ydia Wyse shook rain from her red curls, wishing she could as easily shake memories

of the last time she’d seen Mem’s lowered

kapp

and bowed head, praying for her daughter’s return. Return not only to West Kootenai,

Montana, but to the Amish. Lydia was returning all right, but not in the way Mem had

wished. Tomorrow was Mem’s funeral, and during the nine hours of driving—from Seattle

to Montana—each minute had brought her closer to home. To heartache.

Lydia had stopped for gas in Eureka, about an hour from her parents’ house, and rain

now drenched her long curls. Soaked, standing in line to pay, she spotted a few Amish

women climbing from a white van and hurrying into the grocery store attached to the

gas station. Seeing them, a twinge of familiarity—of longing—filled her heart, but

she stuffed the emotions down.

“Are those Amish from West Kootenai?” she asked the gas station attendant who took

her cash.

He shrugged. “Don’t know. Just Amish. Not really sure where they’re from.”

“

Just Amish

.”

She walked out of the gas station and got back on the road, thinking about the phrase.

All her life she’d wanted to be anything but “just Amish.” Even when she wore the

same type of dress, the same type of

kapp

as the other girls, she’d felt different. When she was sixteen, she’d discovered

why.

The rain stopped its patter on the windshield. Lydia cracked the window, letting the

cool, pine-scented breeze filter in, spreading a spray of curls across her cheek.

She pressed harder against the gas pedal, wishing she could leave the memories behind.

But she could never outrun the dark clouds of her past, no matter how hard she tried.

Picking up speed, her yellow Volkswagen Beetle snaked along the narrow country road.

As she grew closer to West Kootenai, tall mountain peaks pierced the thinning clouds,

rays of sunlight splitting the firmament.

Her mother’s death hadn’t come as a surprise. What

had

surprised her was the faint excitement at seeing those women in their

kapp

s and Plain dress. How could being raised Amish seem so familiar, yet foreign? Painful.

She’d never be “just Amish.” Mem, her adoptive mother, had finally disclosed that

when she’d turned sixteen. Lydia should never have been born. How horrible that her

birth-mother had been traumatized twice—first by her conception and second from her

birth. Since knowing the truth, Lydia had been running, searching for who she was

apart from the Amish community. After all, her birth father was anything but Amish.

Running until now. Her mother’s funeral had forced her to return. Return to her parents’

home. Return to the quiet Amish community where her parents had found healing after

Lydia walked away from their lifestyle and beliefs.

Alongside the road, black—and-white cows dotted a field,

bright green from summer sun and rain. A few lifted their heads when she passed, as

if surprised by the sight of her red hair through the window.

Rain always gave her a fuzzy silhouette. With one hand Lydia held a death grip on

the steering wheel and with the other she pushed the mass of curls back from her face

for the hundredth time that day, wishing she’d had enough foresight to grab a hair

band. That had been the only good thing about wearing a

kapp

during her growing-up years. She could pin her hair up with a dozen pins, tuck it

under the starched white head covering, and forget about it.

A

kapp

. One thing that wasn’t so bad about being Amish. That and the fact she’d had plenty

of time to daydream stories as she mucked stalls, hung clothes on the line, and stitched

perfect designs on dishcloths.

If only life was so simple. She’d told herself she wouldn’t look back—and she rarely

did. But now she had no choice. Like a hook caught into her heart, the truth of who

she was, how she’d been raised, reeled her in.

Truth

. She could only run from it for so long.

Gideon Hooley approached the gelding with easy steps. The horse didn’t cast one look,

but from his perked ears Blue knew he was not alone in the pasture. The horse’s brown

coat shimmered in the sunlight, muscles rippling as he took one step forward. Tense.

At any moment he could turn, chase Gideon down, and trample him. Gideon had seen it

before. But something deep down in his gut told him Blue was different, no matter

what others said.

“Untamable” was how Dave Carash described him. The

Englisch

man blamed it on the fact he’d had to pull the foal after the mother died in labor.

“Poor thing was without oxygen and as blue as the Montana sky,” Dave had said, and

the name had stuck. The problem was the

Englisch

man worked hard to provide for his family and hadn’t given enough time to the temperamental

creature.

Gideon had seen it before. Horse owners often had better intentions than time and

skill, and sometimes Gideon felt that instead of helping people with horse problems

he was actually helping horses with people problems.

He took another step forward. “Beautiful day, isn’t it, Blue?” He walked a wide circle

to approach Blue straight on. Many horses were nearsighted. Things far off scared

them. They needed to see them up close to trust them. But letting anyone come close

was hard. Gideon understood.

The horse tossed his head.

Gideon removed his brimmed hat and turned it over in his hands, letting the sun warm

the top of his head. Mr. Carash had hired him to train Blue, but today was an introduction

of sorts. Gideon hadn’t come with a rope or bridle. He’d come with a soft voice and

an even softer hand.

“I heard some guys tried to chase you down.” Gideon chuckled. “Would have liked to

see that.” He smiled, eyeing the bay with its long neck; fine, clean throatlatch;

and deep, sloping shoulders. The gelding watched him, curious.

Intelligent eyes. With the right training he’ll be a fine horse

.

“Must be hard when you feel threatened.” Gideon’s throat tightened even as he said

those words, and he glanced to his right and looked at the distant hills. “When yer

scared fer your life, I understand. There were things I went through as a kid that

scared me too.”

His gut cinched, and his mother’s words came back to him.

“

Out of all the places to visit…why’d ja want to return to Montana? It’s a

schrecklich

place

.”

“

Scary for a little boy

, ja

, but I’m a grown man now

,” he had told her.

“

Still…do you not mind what happened?

”

“

Getting lost, being scared

, ja

. How could I forget

?” Even as an adult he still dreamed about that night in the woods alone. And his

parents had never let him forget it was his disobedience that had gotten him into

so much trouble.

“

That’s not the only matter

.” Mem’s voice had lowered, and she’d settled into the kitchen chair, preparing to

launch into a story.

His dat strode in with quickened steps, startling them both. “

Leave it no mind, Lovina. It wonders me why you need to bring it up

.”

“

Gideon needs to know the truth at some time

,” she mumbled under her breath.

“

Not

that

truth

.” The words fell from Dat’s lips like horseshoes from a hook. Flat. Hard.

From the look in Dat’s eyes that day, Gideon had known he wouldn’t get his father

to speak a word of it. Mem either. Fine. He didn’t need to hear their story. Something

had happened in West Kootenai, Montana—more than just getting lost on the mountain

when he was four. No one spoke of it, but the hidden truth had haunted his growing—up

years.

Gideon glanced at the skittish horse again. Sympathy caused his heart to ache. This

horse was afraid of a heavy hand. Gideon, on the other hand, feared the truth would

rope him up and cause him harm—not to his body but to his heart.

He continued forward until he stood by the gelding’s side. The wild grasses blew in

the breeze, feathering against his ankles. With a slow, steady movement he reached

up and

stroked the horse’s neck. “There you go, boy. Nothing’s gonna hurt you. You’re a strong

boy. Smart too.”

This morning he’d gone to the West Kootenai Kraft and Grocery and had a large stack

of pancakes, chatting it up with some of the other Amish bachelors. But he’d wanted

to be here instead, with this horse. Even as a kid he found safety and companionship

with horses more than people. Mem said that would change when he met the right woman.

He’d believe that when he saw it.

Gideon had come back to Montana with his cousin Caleb to hunt. They’d arrived two

months ago in April to be eligible for a resident hunting license in November. When

hunting season rolled around and he headed up into the hills for sport, adventure,

and provision, he could forget the past. But until the cold winds blew in and the

season of hunting started, Gideon sought truth.

Do I really want to know?

2

I

t had been a long drive from Seattle. The dreary weather had matched Lydia’s dour

thoughts. Everyone, she supposed, ached when they lost their mother. Maybe her ache

was greater knowing Mem had felt a death at Lydia’s leaving. Yes, they’d seen each

other almost once a year, but it was hard connecting with a woman so opposite her.

Or maybe, like her boss, Bonnie, had said, Lydia had focused on their differences

so she wouldn’t feel so guilty about leaving.

There were many times Lydia had wished she’d kept her mouth shut about her Amish parents

and where she’d come from, but Bonnie was one of those curious types who sought people’s

stories like a schoolboy sought change under a couch cushion when he heard the ice

cream truck. And as she’d handed Bonnie the keys to her studio apartment so Bonnie

could water her five houseplants while she was gone, Lydia hadn’t missed her boss’s

slightly cocked eyebrow and narrow gaze. The look said, “A story’s going to come out

of this.”

Could Bonnie be right? The Amish community she journeyed toward consisted of twenty

families who lived among the

Englisch

in a small mountain community only a few miles

from the Canadian border. With only one store and not even a post office, going there

was like voyaging back thirty years to a place where neighbors counted on each other,

loggers felled tall trees by hand, and children caught fish in mountain streams with

long sticks and twine.

And then there were the bachelors.

She’d been back only one other time during late spring, and the small community had

been buzzing with the presence of almost thirty Amish bachelors. As her mother had

explained, a group of young men arrived every spring to live and work for six months

to obtain their residence license so they could legally hunt in the fall. Six months

to scope the mountains for game. Six months to live in the crosshairs of young women

who hoped a bachelor would return home with not only an eight-point buck, but her

as a bride.

The country music station Lydia had picked up played a mournful love song, and she

reached over and flipped off the noise. Foolishness. All of it.

The road straightened for a spell, and Lydia glanced at the pile of spiral-bound manuscripts

sitting on the passenger’s seat. She edited nonfiction books and the occasional romance

novel—not that Lydia knew a thing about that in real life. Bonnie called her old-fashioned.

Bonnie meant her work style, but Lydia knew it was more than that. She had a television

and a microwave and drove a car, but one thing Lydia hadn’t gotten used to was working

on a computer. When giving her an editing project, Bonnie was gracious enough to print

and bind the manuscripts. And after Lydia was done, Bonnie hired someone to enter

all her work into the computer.

“

For anyone else, Lydia, I wouldn’t do it. But you’re good. Really good. You see words

differently than others. You gather them like wildflowers and arrange them like a

bouquet on the page.

”

It was a kind compliment, but it didn’t satisfy. Lydia enjoyed editing, but what she

really wanted to do was write a book. She wrote little things for their company newsletter,

but she waited for “the” book idea like a rooster watched for the first light of dawn.

It hadn’t come, but it was out there…right over the horizon. And maybe returning to

West Kootenai would spur an idea. After all, how many other book editors traveled

to the mountains of Montana to bury their Amish mother?

Mother

. The word had caused more confusion than peace over the years. Ada Mae Wyse was the

mother who’d taught her Scriptures on her knee, but the woman who birthed her haunted

Lydia’s thoughts. Lydia’s conception—a secret she hadn’t told a soul since first hearing

Ada Mae’s explanation of her birth—would make a tragic story, all right, but not one

she’d write about. Not now. Not ever.

The bridge over Lake Koocanusa glistened in the misty rain. Her vehicle was the only

one crossing the wide expanse, and she glanced for the briefest second at the shimmering

blue water below. When her parents had first moved to the area there’d been an accident

on the lake, and an Amish woman had drowned. A shiver ran up Lydia’s spine thinking

about it. She bit her lip, tightened her hands around the steering wheel, and focused

her eyes to the road as a hollow ache filled her stomach. It pressed against her organs

and lungs, making it hard to breathe. Tragedy struck the

Englisch

and Amish alike. She should know that. Her life wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for

tragedy.

Make that

tragedies

.

She squared her shoulders and prepared for the jarring where the smooth pavement of

the bridge ended and the road turned to dirt and gravel. None of the roads from here

on out were paved.

She climbed the mountain at a steady rise for the next fifteen minutes. Finally the

road flattened out.

Almost there

.

After another few minutes of driving, homes began to dot the roadway. It was easy

to tell which were Amish. They were simply built, and all had white curtains in the

windows; anything with color or pattern would be deemed too proud in their eyes.

A small log schoolhouse sat in the distance. A warmth filled her chest as she thought

about her favorite teacher in Ohio, Miss Yoder. She’d only taught for three years

before getting married and starting a family. But Lydia’s memories included field

trips to the cheese factories in Sugarcreek, softball games with neighbor schools

near the end of the school year, and sleepovers with the other girls at Miss Yoder’s

house. They talked about places Miss Yoder had traveled, visiting family. It had been

the first time Lydia considered life beyond her small community.

Lydia’s cell phone rang, causing her to jump. She hadn’t had cell service for most

of the last few hours—it had been spotty after leaving Kalispell.

As a habit, Lydia pulled to the side of the road before answering.

“Hello?”

“Lydia, it’s Bonnie.”

Lydia smiled. Her boss said the same thing every time she called. She’d worked with

Bonnie for the last two years. She knew her number, her voice.

Lydia put her car into Park and turned it off. “Hey, Bonnie, did the Murphy project

get to the printers?”

“Yes, just an hour ago. I thought you’d want to know.”

Lydia tapped her fingers on the steering wheel. In her

peripheral vision a horse galloped in the fenced pasture. That wasn’t something one

saw every day in Seattle.

“I’m excited.” Lydia pulled her attention back to the phone call. “It’s a great story.

I couldn’t imagine trying to home educate three sets of twins.”

“Didn’t you go to a school like that?” Bonnie asked.

“Like what?”

“A small Amish school with just a few kids.”

“We had twenty scholars, and it seemed a lot to me, especially being an only child.”

“An only child in an Amish home. Seems like an interesting book, don’t you think?”

Lydia sighed, grabbed her camera from the front seat, and stepped out of the car.

There was a large pothole filled with water right outside the driver’s door. She hopped

over it and then juggled everything as she removed and placed her lens cap on the

hood, turning around to where the sun bathed the high mountain peaks with golden light.

To write about her family would bring up her adoption, and then someone might become

curious about her birth. No, that couldn’t happen.

Lydia tucked her cell phone between her shoulder and jaw and focused the camera on

the mountains, snapping a shot. “Nothing about my life is typical Amish.”

“Except for the fact you like to cook, which seems completely Amish to me.”

“Yes, there’s that.”

“Which is why I’m calling. I think you should write a book about being Amish.”

“Um, except for the fact that I left the community, remember?” Lydia’s eyes swept

the field. They fixed on a structure at the far end of the pasture. She gasped. Then,

with a sad smile,

she lifted her camera and pointed it toward the simple Amish homestead, snapping a

shot. She’d never realized that her parents’ home could be seen from the main road.

“I’m serious, Lydia. Amish books are selling like crazy. I’ve had three distributors

ask me if we had any Amish in our lineup.”

“You didn’t tell them we did…

did you

?”

Bonnie offered a nervous chuckle. “I said there was something we were considering.

How hard would it be to just become Amish again and write about it? You grew up that

way.”

Lydia moaned. “You don’t know what you’re asking—what that would entail.”

“Yes, but it’s a part of you. Your heritage, your cooking. The way you only pay with

cash. Gee, just look at your apartment. I’m certain I could go in there with one small

box and pack up all your personal items and your five houseplants and rent it to a

college student who’d feel quite at home in its dormlike setting.”

“Bonnie—”

“Which I totally could do if you decided to stay longer—”

“Listen, I’m not going to ‘just become Amish again’ to get a book contract. It’s not

just a lifestyle; there’s spiritual meaning too.” Lydia shrugged, watching the movement

of her shadow. “And even if I wanted to go back, I’m not even sure God would take

me.”

Lydia expected a lecture. Instead Bonnie released a low sigh.

“Well, then talk to Him about it, won’t you? I never guarantee anything until it’s

in writing, but by the eagerness of our distributors I’m as close to making a guarantee

as I can be.”

“I’ll think about it…but don’t get your hopes up.” Yet even as she said the words,

Lydia’s heart galloped, just like the horse in the field. She glanced through the

windshield at

the manuscripts in the passenger’s seat and imagined a cover with her name on it.

She pictured choosing a random city, flying there, and walking into a bookstore to

find her book—

her book

—on the shelf. Mem had told her that her life was a gift, that God didn’t make mistakes.

Lydia bit her lip, warmth filling her chest. Maybe following her dream and listening

to Bonnie’s advice would prove Mem to be right.

“I don’t know what happened to you—what made you run. I’m not sure I’ll ever know.

But any given moment you have the chance to redeem your story, Lydia. There’s something

God’s going to do with you in Montana. I can feel it.”

Lydia sighed. She’d gotten used to Bonnie talking about God. While Lydia believed

in Him, she had a hard time believing God was concerned about her life, her problems.

A small group of sparrows fluttered through the pasture’s grass. Out of nowhere a

thought—a Scripture verse she’d learned in school—filtered through her mind: “

Are not two sparrows sold for a farthing? and one of them shall not fall on the ground

without your Father.

”

She was about to tell Bonnie to drop the idea when a stirring fluttered in her heart

as soft and light as her curls bouncing on the breeze.

Do I care for you?

I care for the sparrows, don’t I?

The words weren’t audible, but they pierced Lydia’s heart.

She looked around at the pasture, the trees, and the small Amish homestead in the

distance. The warmth expanding in her chest was her first draw to “home” since leaving.

Finding Home

. It was the first twinge that a book—a real book—resonated inside her.

Lowering the camera with her right hand, Lydia took the phone from the crook of her

neck with her left and pressed

it more tightly to her ear. Her fingers trembled. The breeze picked up, carrying the

scent of wild roses on its tail feathers.

“Maybe I will write down what returning home means to me, but don’t count on me seeking

publication. There are just too—” She blew out a breath. “There are some things I

can write only for myself.”

A car sped up the road, then jerked to the side and parked unexpectedly. Blue reared

up. Gideon jumped back and raised his arms up as protection from Blue’s hooves in

case the horse turned. He didn’t. Instead Blue took off across the field, galloping

at full stride.

Gideon grabbed his hat and tossed it to the ground. “

Lecherich!

Ridiculous!” He eyed the yellow car, knowing it had to be a tourist. Sure enough,

a ball of red hair with a heart-shaped face and slim figure climbed out of the car.

He watched as with one smooth motion she took out her camera and snapped photos, first

of the mountains and then of one of the Amish homesteads.

Tourist

.

No one in the area drove as such. No one would intrude by taking photos of a place

without asking. Angry tension tightened his shoulders. First, that he’d have to start

over with Blue, warming the horse up to him again. Second, that he’d have to educate

another

Englisch

woman about what respect meant. What privacy meant.

Growing up in Bird-in-Hand, Pennsylvania, he’d seen tour buses of folks armed with

cameras. He’d been followed by cars, with passengers taking photos. His buggy had

been hit before because a driver veered too close to get a good shot.

Gideon took two steps forward and swooped up his hat from the ground, brushing it

off. Good thing he was around to talk to the woman—young children walked these roads

during the long summer days. He’d hate to see anything happen because she was trying

to get a good photo of “primitive” people to take back and show her friends.

Gideon shook his head as he strode her direction. Frustration dammed up in his throat,

and his heartbeat quickened. Some folks didn’t have a lick of sense.

Lydia looked through the viewfinder of her camera. Her throat grew raw. Laundry fluttered

on the clothesline behind her parents’ place, evidence of her mother’s work. She guessed

it had been hanging a couple of days. Dat most likely hadn’t even noticed it in his

grief.

She turned away. Bonnie was relating a story about her mother’s funeral. How come

people always did that? As soon as you lost someone, friends were compelled to describe

their own family member’s passing. It didn’t help, except to make Lydia realize even

more that no one walked this earth without loss, without pain.