The Norm Chronicles (10 page)

Read The Norm Chronicles Online

Authors: Michael Blastland

Everything a mother does is wrong, she thought, when she woke, disturbed, and later read that the dangers of life are infinite and among them is safety, according to Goethe, apparently. ‘Thanks,’ she said.

‘Just a little scratch,’ she said to Prudence after breakfast. ‘Everyone has it. You can have a plaster.’

Because if safe could be dangerous, and the dangerous things were only allayed with more danger, which was really safe, and how risky was safety? Or whatever. Bloody Goethe. Bloody advice.

‘It’s to protect you,’ she said, as Prudence sat in her TripTrap chair, colouring with little arms.

On the kitchen table lay printed pages from the Student Vaccine Liberation Army, ‘armed with the most powerful knowledge’ to

encourage critical thinking about ‘the risks and dangers of vaccines.’,

1

which explained how

In England in the earlier centuries hatters used to use mercury to stiffen the felt of hats. The mercury was absorbed into their fingertips and they eventually went ‘mad’ … MAD AS A HATTER. We are injecting mercury directly into our children’s arms causing an epidemic of apparent madness … ADHD, ADD, Autism, OCD, Bipolar … are vaccine injuries mis-labelled as mental illness.

A leaflet from the doctor said:

All medicines (including vaccines) are thoroughly tested to assess how safe and effective they are. After they have been licensed, the safety of vaccines continues to be monitored. Any rare side effects that are discovered can then be assessed further. All medicines can cause side effects, but vaccines are among the very safest.

2

Bad if you do, bad if you don’t, bad to Pru, bad to others. Preying on her mind were vaccination horror stories about children who died or suffered because they were

not

protected from common illnesses. ‘If only we had given him the jab,’ they said. If they had only vaccinated their own child, their friend’s baby would not have been exposed to the virus before vaccination and would still be alive.

On her laptop was another mother’s story: after jabs for hepatitis her baby screamed incessantly, hardly slept, didn’t feed, woke one morning vomiting, was airlifted to hospital, survived with ‘seizure disorder, cortical blindness, severe reflux and high risk for aspiration pneumonia … severe developmental delay … a mixture of hypotonia … some spasticity’, needing 24-hour care by two people.

3

On the news last night was a report of a warning sent to schools about measles abroad, the risk of travelling if not immunised and the potential complications: eye and ear infections, pneumonia, seizures

and, more rarely, encephalitis – swelling of the brain, brain damage and even death.

4

On top of everything else on the table was an appointment card.

In the end she went, telling herself to calm down but helpless with guilt, and for three whole days her heart beat at her conscience while she watched, and waited.

WHAT IF PRUDENCE

had the jab and then soon afterwards began to show signs of autism? Is the story that her mum’s decision to vaccinate was catastrophic? The truth is, we don’t know exactly what causes autism – although there are plenty of theories. But when one thing follows another, the easiest story to tell is that one caused the other. So whatever she does, Prudence’s mother feels she will be in the dock for whatever happens, as storytelling joins the dots in hindsight with any emotional glue, fear, politics, prejudice or presumption that come to hand to tell us that she got it wrong. Pity the mother, who can’t win against risk when stories come to be told, after the event.

Pity the small boy too. When DS was a lad, there were no vaccinations against measles, mumps and chickenpox, so when anyone local had them he was marched round to be infected. The rule of thumb was that, if you were going to get it, it was best to get it over with now. Vaccination is a set of uncomfortable trade-offs, because DS now knows that measles exposed him to around 200 MicroMorts.

*

But there wasn’t much choice back then, and no doubt it was character-forming.

Measles was common in the 1950s, the effects well known, complications not unusual. It can cause blindness and even death. Observe that in your neighbours’ children and you cry out for protection. Because it was common, people saw it around, a clear and present danger they wanted rid of. Now that we don’t see it so much, some cry instead for protection from vaccines. Visibility plays a big part in risk.

Given a choice between harm you can see and harm you can’t, what would you do? Some avoid the one they can see – more threatening

than a danger that’s not here and now. Some take bigger fright at invisible risks, such as radiation, which seem more sinister. Others try for a cool-headed calculation of the pros and cons. And some of us simply do what the doctor tells us.

The simple point here is that ‘risk’ is more typically about ‘risks’, plural, and these risks often point in different directions: some immediate, some distant, some visible, some latent. How are you supposed to decide which risk to take when you are often judged not by the fact that you did your best in all good faith in a state of uncertainty but by how it turned out? Pru’s mum sits at the table beset by tragic endings.

If she types ‘vaccine safety’ into her browser, she will see mostly official sites full of reassurance. If she types ‘vaccine risk’, she will find claims that children are harmed, that the science is bunk and the scientists are not to be trusted.

Vaccination ticks many of the fear factors that arouse strong emotions (see also

Chapter 19

, on radiation). Children are not even sick before we inject them. Actively sticking a needle in your child’s arm is a sin of commission that hurts in ways that doing nothing doesn’t – at least, not straight away.

Vaccination is also imposed, either through pressure or legal compulsion: if your child is to attend a kindergarten in Florida, for example, they must have been vaccinated against DTaP (diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis, or whooping cough), Hepatitis B, MMR (measles, mumps and rubella, or German measles), polio and varicella (chickenpox).

5

There can be side-effects. Finally, multinational corporations make a lot of money out of this mass-medicalisation.

All of which can provoke fierce opposition. And so claims that vaccination may cause dread outcomes such as autism find a ready audience, particularly in the US (although perhaps they compensate by not caring so much about GM foods).

At least children don’t need to be vaccinated against smallpox any more, eradicated after the last natural case appeared in Somalia in 1977 (although a UK laboratory worker died in 1978). Smallpox killed countless numbers throughout history, with 2 million deaths a year right up to the 1950s. It helped Europeans conquer the Americas by almost wiping

out the native populations. But it had long been observed that survivors did not contract the disease again, and the practice of

inoculation

developed, in which extracts from scabs were scratched onto the skin to give a deliberate but hopefully mild infection.

Then in 1796 Edward Jenner used another, much milder disease, in this case cowpox, after it was noticed that milkmaids tended not to have smallpox. Hence

vaccination

, from the Latin

vacca

(‘cow’). Being scraped with pus taken from someone who had been exposed to an infected cow’s udder isn’t an obviously attractive idea, so naturally it was tried on a small boy – James Phipps, aged eight, the son of Jenner’s gardener. Whether he gave informed consent is not recorded.

Moving vaccine around in the early days was tricky without refrigeration. The answer, as ever: small boys. To ferry cowpox to the Spanish Americas in 1803 – a voyage so long that one infected person would recover – eleven pairs of orphans were press-ganged into service and the first pair infected before they set sail. In time, they passed it on to the next pair, and so on for the duration of the voyage until good, fresh cowpox pus arrived in the New World. It took a while to catch on, but immunisation (which covers both inoculation and vaccination) went on to save millions of lives.

The history of measles offers a clue about the risks without immunisation. In England and Wales in 1940 there were 409,000 cases, of whom 857 died,

6

a ‘case fatality rate’ of 0.2 per cent or 2,000 Micro-Morts, the same as that quoted by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the US.

7

Vaccination started in the 1960s, and by 1990 the number of cases had dropped to 13,300, with one fatality. Since 1992 there have been no childhood deaths from measles, only as adult consequences from early infection.

Vaccination can also be used to reduce long-term harm: it’s been estimated that one cancer in every six is caused by infection,

8

but the long period between infection and illness make the association hard to spot. Nevertheless the HPV vaccine is now offered to 12-year-old girls to help prevent the infection that can lead to cervical cancer.

So it seems a good thing to be vaccinated. Rather like stopping smoking, it is also good for people around you. This is because of herd

immunity, when sufficient numbers of people are immune for an infection not to turn into an epidemic. What ‘sufficient’ means depends, in a fairly simple way, on how infectious the disease is. For example, a single person with smallpox would infect, in a community of susceptible people such as the Incas, on average around 5 others.

*

If they in turn infect 5 each, and so on, then it will only take six steps to infect an entire community of 50,000 people.

Given the infection rate for measles, we need to vaccinate 92 per cent of the population to prevent the spread of an epidemic.

†

The rate in three years of the mid-2000s was 82 per cent, 80 per cent and 81 per cent. By 2011 it had recovered to 89 per cent.

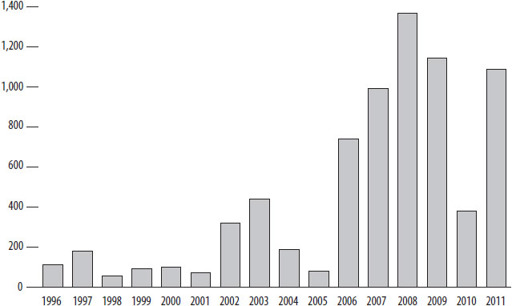

Figure 10

(overleaf) shows what happened for cases of measles in England and Wales.

Figure 10:

Confirmed cases of measles in England and Wales, 1996–2011

The fact that any one of us can have most of the benefit of vaccination without actually being vaccinated is known as a ‘free-rider’ problem. You can rely on other people to keep the risk low – as long as they don’t stop too.

So, is it risky not to be vaccinated? It is, and it isn’t. The risk could be nil, and it could be huge. That is because it depends on what other people do, as well as what you do. If they all carry on vaccinating and you stop, you’ll probably be fine. If they stop too, you could be in trouble. The risk is dynamic and contingent. We are both subject to the risk – from others – and we are the risk, because we could become infectious.

So exactly the same behaviour on our part can mean extreme differences of risk, depending on what other people do. This makes reliable numbers about the risks that you face as an individual impossible to calculate. There’s a big risk down the road for all of us if there is a failure of herd immunity, but what that means for you, now, is impossible to say. You could be fine. But what if you contribute to a loss of herd immunity? You could be dead. So, what’s the risk?

But there is no denying that vaccines can have side-effects. For example, the UK Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency

(MHRA) publishes the adverse event reports received following at least 4 million doses of the HPV Cervarix vaccine.

10

There were 4,445 reports listing 9,673 reactions, although these reports are voluntary, and so the rough rate of 1 report per 1,000 injections is a major underestimate. The US CDC warns of mild to moderate reactions in 1 in 2 cases.

11

Most of the MHRA reports are minor consequences of the injection such as pain and rash, and over 2,000 were considered ‘psychogenic’, caused by the injection process rather than the vaccine itself, including dizziness, blurred vision and cold sweats.

The problem comes with rare but severe events that occur later, and it is debatable whether these were due to the vaccine or would have occurred anyway. The MHRA lists over 1,000 reported reactions that they do not recognise as associated with the HPV vaccination, including four cases of chronic fatigue syndrome. Given the number of 12- to 13-year-old girls in the programme, the MHRA estimated they would expect to see 100 new cases of chronic fatigue syndrome over this period anyway, regardless of vaccination, so it is remarkable how

few

cases have been reported. But those families may well be convinced that the vaccine caused their child’s condition. It is the ‘available’ thing to blame.

The real problem is that with any mass intervention there will always be bad occurrences around the time of the jab – essentially, coincidences. For example, in September 2009 the

Daily Mail

’s headline declared that ‘Schoolgirl, 14, dies after cervical cancer jab’

12

and quoted the head teacher as saying, ‘During the session an unfortunate incident occurred and one of the girls suffered a rare, but extreme reaction to the vaccine.’ Three days later it was revealed that the girl had cancer and the death was coincidental:

13

however this was not headline news, and this tragic event is used repeatedly on websites as proof of the dangers of the HPV vaccine.