The Norm Chronicles (13 page)

Read The Norm Chronicles Online

Authors: Michael Blastland

Better than public information films and their selective images – don’t you think? – is private information. ‘I know from personal experience …’ are the kind of words we use with all the plumped-up authority we’ve got, certainly more authority than we grant governments. But personal experience and sex? Authoritative and rigorously unbiased? Not selective? Yeah, sure.

Let’s say you have unprotected sex, like Kelvin and Kath. If nothing goes wrong, you feel relieved. But you might also feel the risk probably wasn’t that high after all. Exposure to danger can have that effect – of making people feel safer. ‘See, it was OK!’ One formal explanation for this is that small samples of rare events are skewed. This means that when bad results are not typical – say only one time in every 20 – you might get away with the first few so you expect to be fine next time too. Your chance of being all right is 19 out of 20, or 95 per cent.

In truth, you shouldn’t deduce anything about the true odds from one experience. But deduce you will. Based on your own massively selective sample of the past, you might learn to underestimate probabilities in the future. ‘Had shag, no kid’, as Kelvin might say. Do this a few times and he will – probably – still be OK, encouraging him to think – as if he needs encouragement – that this is the sort of risk he can take.

On the other hand, if it all goes wrong, people tend to overestimate the risk that it will go wrong again. Suppose unsafe sex leads to an STI

about one time in 50. It doesn’t, but bear with us. People might not know the figure, even roughly. After 100 people have five encounters each, roughly ten have an STI.

These ten might say, ‘Crikey, we did it only five times and look what happened.’ So they take away an exaggerated sense of the odds. The other 90 might imagine that the probability of danger is not much above zero: ‘Well, it never happened to me.’ There are lab experiments – not involving sex – that seem to confirm this pattern of belief and behaviour.

So personal experience can lead us astray. Again, we need bigger data than just our own notches on the bedpost.

Sex, like so many other fun activities, clearly carries dangers. These range from pregnancy (if you are a woman having sex with a man and don’t want to be pregnant), potentially dangerous disease or mild irritation, heart attack, injury when the bed collapses, to hurt feelings – not even a phone call? – the chance of embarrassment or arrest if caught in a public place.

Let’s start, as most of us did, with simple, unprotected sex between a man and a woman. What is the chance that any one of Kelvin’s romantic encounters will end in a pregnancy? This too, for understandable reasons, is difficult to study in laboratory conditions. A New Zealand study in which participants were only allowed to have sex once a month suffered, unsurprisingly, from a high drop-out rate. Perhaps the closest has been a European study that recruited 782 young couples who did not use artificial contraception and who carefully recorded the date of every act (and there were a lot of them) until there had been 487 pregnancies.

2

The time of ovulation was estimated for each menstrual cycle.

*

The bottom line is that a single act of intercourse between a young couple has on average a 1-in-20 chance of pregnancy – this assumes the opportunity presents itself on a random day, as these things sometimes do when you’re young.

People who study how populations change are called demographers, and they use the term ‘fecundability’ for the probability of becoming pregnant during one menstrual cycle. This varies between couples, but the average is estimated to be between 15 and 30 per cent in high-income countries.

We can use the lower figure to illustrate the consequences for an average couple trying to have a child: there is an 85 per cent chance of finishing each month without conceiving, and if we assume each month is the same and independent, then there is a 0.85 x 0.85 x … x 0.85 (12 times) chance of not getting pregnant in a year of trying, which is 14 per cent. So fecundability of 15 per cent means a 100 – 14 = 86 per cent chance of getting pregnant in a year: a figure of 90 per cent is often quoted as the proportion of young couples who will be expecting a child after a year without contraception, which corresponds to a fecundability figure of 18 per cent.

Fecundability can be estimated from large populations if there is no effective contraception. In Europe this means going into history: over 100,000 births taken from registers in France between 1670 and 1830 have been analysed to produce an estimate of average monthly fecundability of about 23 per cent.

3

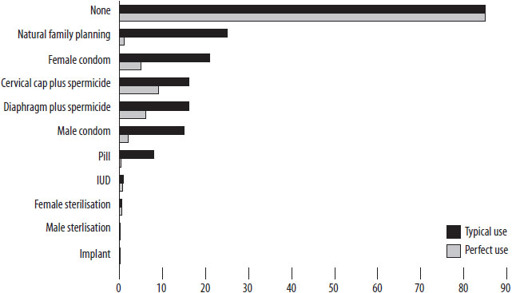

But suppose you don’t actually want to get pregnant – how much is fecundability reduced by different types of contraception? This is generally expressed as the pregnancy rate following one year of use and strongly depends, of course, on how careful you are.

Contraceptive pills, intrauterine devices, implants and injections are quoted as 99 per cent effective, so that less than 1 in 100 users should be pregnant after a year, while male condoms are around 98 per cent effective if used correctly, and diaphragms and caps with spermicide are said to be 92–96 per cent effective, so between 4 and 8 women using them will be pregnant after one year.

4

Imperfect, or what’s often referred to as ‘typical’, use of contraceptives – you threw up the pill in the gutter on

Friday night, forgot, it fell off, etc. – is, unsurprisingly, a lot less effective.

Figure 11:

Percentage of women pregnant after one year with selected forms of contraception

5

The cervical cap pregnancy rate shown here should be about doubled for women who have previously given birth. That is, the cap is only half as effective if you’ve already had a baby. The natural family planning ‘perfect-use’ rate varies from 1 per cent to 9 per cent pregnancies, depending on method. Failure rates for condoms are the figures without the use of spermicide. Other figures, from the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE), indicate a failure rate for the contraceptive implant Implanon of less than 0.1 per 100 women over five years, better even than the numbers we’ve used here, and by some way the most effective form of contraception, according to the NICE data. Note that this doesn’t address possible side-effects.

One way to make these comparisons is to imagine a woman considering various contraceptives. Assume an infinite sex life. How long before she typically becomes pregnant? In the case of female sterilisation, about 200 years. The failure rate is one pregnancy for every 200 woman-years. So if 200 women took it for one year, one would be expected to become pregnant. For contraceptive implants the failure rate is so low that an accurate figure is hard to calculate. By one estimate, it is about one pregnancy every 2,000 woman-years.

If they don’t have access to contraception, then women can end up having a

lot

of children. The French data showed that women in the 1700s who married between 20 and 24 had on average 7 children each, as women still do in Niger and Uganda.

Total Fertility Rate

is the average number of children expected per woman if current fertility carried on through her life. It took the UK more than 200 years to reduce the

number of births per woman from 5.4 in 1790 to 1.9 in 2010, while other countries have shown a similar decline in just a generation: Bangladesh took only 30 years to go from 6.4 in 1980 to 2.2 in 2010.

*

Some countries have a remarkably low fertility rate, particularly prosperous countries in South-East Asia (Singapore’s is only 1.1) and countries in Eastern Europe – the Czech Republic’s is 1.5, well below what is necessary to replace the population.

Pregnancy is not generally considered a great idea for young girls. In 1998 in England 41,000 girls aged between 15 and 17 conceived – that’s 47 in every 1,000, or 1 in every 21. Imagine that at school. The UK government set a target to halve this rate by 2010, and by 2009 the headline figure had dropped to 38 per 1,000 girls, which is an important fall but a fraction of the target. There is wide variation in these rates around the country – from 15 per 1,000 in Windsor and Maidenhead to 69 in Manchester: that’s 1 in every 15 girls aged between 15 and 17, pregnant every year. There is a strong correlation with low educational attainment, and deprived seaside towns traditionally have high rates, with 1 in every 17 pregnant in Great Yarmouth each year, and 1 in every 16 in Blackpool

7

.

Nearly half of these teenage pregnancies end in abortions, but there are still many births. A 2001 report

8

put the UK highest in Europe, with 30 births per 1,000 women aged 15 to 19, with only the USA exceeding it among high-income OECD countries, at 52 births per 1,000. This is in staggering contrast to countries such as South Korea, Japan, Switzerland, the Netherlands and Sweden, which all have birth rates of fewer than 7 per 1,000 teenagers.

Of course, we could turn these dangerous odds around and make them the measure of hope for those who want to have a baby. Pregnancy isn’t always well described as a risk – it can obviously also be a blessing.

Which you can’t really say about disease and infection. HIV, syphilis, gonorrhoea, chlamydia, hepatitis and numerous other STIs – some potentially fatal, some unpleasant – are a danger of unprotected sex of various kinds, and some even with protection, whenever there is a chance your partner is infected.

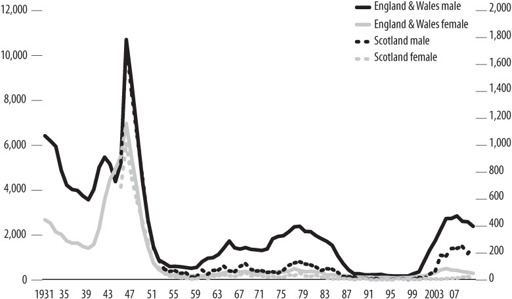

Figure 12:

Historical number of diagnoses of syphilis in England and Wales (left-hand axis) and Scotland (right-hand axis) for men and women, GUM clinics

Risks are higher for young adults, men who have sex with men, and people who inject drugs, and black African and black Caribbean men and women continue to be disproportionately infected. The peak risk in women tends to be among those aged 19 or 20, and in men a few years later.

There has been an increase in the number of diagnoses for many STIs in the past ten years, partly because people’s behaviour has changed, mostly because we are simply testing a lot more people through screening programmes and using more sensitive tests.

But the longer-run data are fascinating.

Figures 12

and

13

reveal a rich history of behaviour linked to world events – wars, social shifts in attitude, AIDS and medical discovery – all expressed through sexual risk. Just look at 1946 in

Figure 12

, the chart on syphilis – and draw your own conclusions (noting that penicillin became widely available soon after).

The chance today that you’ll catch something after one sexual encounter with an infected person is not a figure medical authorities like to throw around. It is extremely dependent on your partner’s background, which disease they have and what you get up to.

Very roughly, the HIV risk for a woman with a man has been put at

about 0.1 per cent (meaning that if she has sex with 100 infected men she will have a 1 in 10 chance of becoming infected herself); for a man with a woman it has been put at 0.05 per cent, or one infection per 2,000 ‘events’; and for a man with a man it goes up to 1.7 per cent depending whether you are ‘insertive’ or ‘receptive’. But there are plenty of stories of once being enough.

9

Figure 13:

Historical number of diagnoses of gonorrhoea, England and Wales, GUM clinics