The New Penguin History of the World (154 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

Why this happened has been much debated. Clearly one part of the story is that of the sheer momentum of accumulated forces. The European hegemony became more and more irresistible as it built upon its own strength. The theory and ideology of imperialism were up to a point mere rationalizations of the huge power the European world suddenly found itself to possess. Practically, for example, as medicine began to master tropical infection and steam provided quicker transport, it became easier to establish permanent bases in Africa and to penetrate its interior; the Dark Continent had long been of interest but its exploitation began to be feasible for the first time in the 1870s. Such technical developments made possible and attractive a spreading of European rule which could promote and protect trade and investment. The hopes such possibilities aroused were often ill-founded and usually disappointed. Whatever the appeal of ‘undeveloped estates’ in Africa (as one British statesman imaginatively but misleadingly put it), or the supposedly vast market for consumer goods constituted by the penniless millions of China, industrial countries still found other industrial countries their best customers and trading partners. Former or existing colonies attracted more overseas capital investment

than new acquisitions. By far the greatest part of British money invested abroad went to the United States and South America; French investors preferred Russia to Africa, and German money went to Turkey.

On the other hand, economic expectation excited many individuals. Because of them, imperial expansion always had a random factor in it which makes it hard to generalize about. Explorers, traders and adventurers on many occasions took steps which led governments, willingly or not, to seize more territory. They were often popular heroes, for this most active phase of European imperialism coincided with a great growth of popular participation in public affairs. By buying newspapers, voting, or cheering in the streets, the masses were more and more involved in politics, which, among other things, emphasized imperial competition as a form of national rivalry. The new cheap press often pandered to this by dramatizing exploration and colonial warfare. Some also thought that social dissatisfactions might be soothed by the contemplation of the extension of the rule of the national flag over new areas even when the experts knew that nothing was likely to be forthcoming except expense.

But cynicism is no more the whole story than is the profit motive. The idealism which inspired some imperialists certainly salved the conscience of many more. Men who believed that they possessed true civilization were bound to see the ruling of others for their good as a duty. Kipling’s famous poem urged Americans to take up the White Man’s Burden, not his Booty.

Many diverse elements were thus tangled together after 1870 in a context of changing international relationships which imposed its own logic on colonial affairs. The story need not be explained in detail, but two continuing themes stand out. One is that, as the only truly worldwide imperial power, Great Britain quarrelled with other states over colonies more than anyone else – its possessions were everywhere. The centre of its concerns was more than ever India; the acquisition of African territory to safeguard the Cape route and the new one via Suez, and frequent alarms over dangers to the lands which were India’s north-western and western glacis, both showed this. Between 1870 and 1914 the only crises over non-European issues which made war between Great Britain and another great power seem possible arose over Russian dabblings in Afghanistan and a French attempt to establish themselves on the Upper Nile. British officials were also much concerned about French penetration of West Africa and Indo-China, and Russian influence in Persia.

These facts indicate the second continuing theme. Though European nations quarrelled about what happened overseas for forty years or so, and though the United States went to war with one of them (Spain), the partition by the great powers of the non-European world was amazingly

peaceful. When a Great War at last broke out in 1914, Great Britain, Russia and France, the three nations which had quarrelled with one another most over imperial difficulties, would be on the same side; it was not overseas colonial rivalry which caused the conflict. Only once after 1900, in Morocco, did a real danger of war occasioned by a quarrel over non-European lands arise between two European great powers and here the issue was not really one of colonial rivalry, but of whether Germany could bully France without fear of her being supported by others. Quarrels over non-European affairs before 1914 seem in fact to have been a positive distraction from the more dangerous rivalries of Europe itself; they may even have helped to preserve European peace.

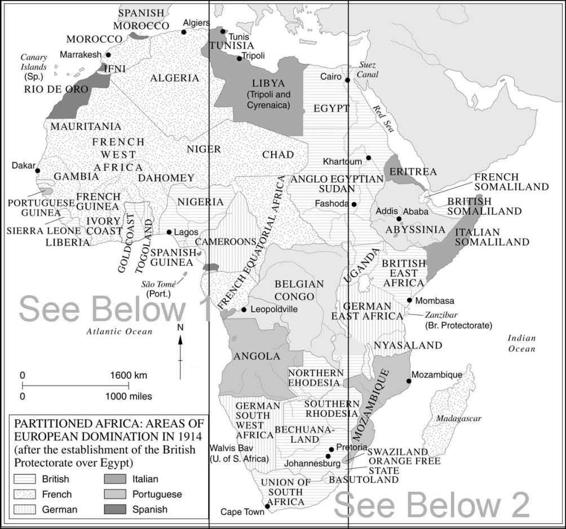

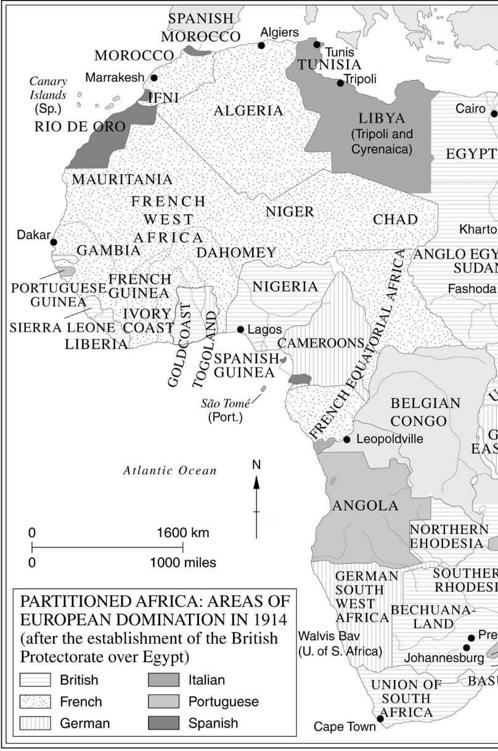

Imperial rivalry had its own momentum. When one power got a new concession or a colony, it almost always spurred on others to go one better. The imperialist wave was in this way self-feeding. By 1914 the most striking results were to be seen in Africa. The activities of explorers, missionaries, and the campaigners against slavery early in the nineteenth century had encouraged the belief that extension of European rule in the ‘Dark Continent’ was a matter of spreading enlightenment and humanitarianism – the blessings of civilization, in fact. On the African coasts, centuries of trade had shown that desirable products were available in the interior. The whites at the Cape were already pushing further inland (often because of Boer resentment of British rule). Such facts made up an explosive mixture, which was set off in 1881 when a British force was sent to Egypt to secure that country’s government against a nationalist revolution whose success (it was feared) might threaten the safety of the Suez Canal. The corrosive power of European culture – for this was the source of the ideas of the Egyptian nationalists – thus both touched off another stage in the decline of the Ottoman empire of which Egypt was still formally a part and launched what was called the ‘Scramble for Africa’.

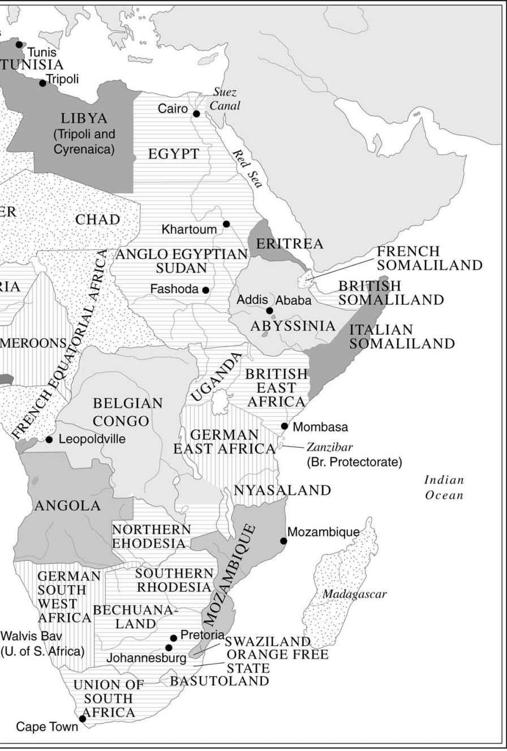

The British had hoped to withdraw their soldiers from Egypt quickly; in 1914 they were still there. British officials were by then virtually running the administration of the country while, to the south, Anglo-Egyptian rule had been pushed deep into the Sudan. Meanwhile, Turkey’s western provinces in Libya and Tripoli had been taken by the Italians (who felt unjustly kept out of Tunisia by the French protectorate there), Algeria was French, and the French enjoyed a fairly free hand in Morocco, except where the Spanish were installed. Southwards from Morocco to the Cape of Good Hope, the coastline was entirely divided between the British, French, Germans, Spanish, Portuguese and Belgians, with the exception of the isolated black republic of Liberia. The empty wastes of the Sahara were French; so was the basin of the Senegal and much of the northern side of that of the Congo. The Belgians were installed in the rest of it on what was soon to prove some of the richest mineral-bearing land in Africa. Further east, British territories ran from the Cape up to Rhodesia and the Congo border. On the east coast they were cut off from the sea by Tanganyika (which was German) and Portuguese East Africa. From Mombasa, Kenya’s port, a belt of British territory stretched through Uganda to the borders of the Sudan and the headwaters of the Nile. Somalia and Eritrea (in British, Italian and French hands) isolated Ethiopia, the only African country other than Liberia still independent of European rule. The ruler of this ancient but Christian polity was the only non-European ruler of the nineteenth century to avert the threat of colonization by a military success, the annihilation of an Italian army at Adowa in 1896. Other Africans did not have the power to resist successfully, as the French suppression of Algerian revolt in 1871, the Portuguese mastery (with some difficulty) of insurrection in Angola in 1902 and again in 1907, the British destruction of the Zulu and Matabele, and, worst of all, the German massacre of the Herrero of South-West Africa in 1907, all showed.

This colossal extension of European power, for the most part achieved after 1881, transformed African history. It was the most important change since the arrival in the continent of Islam. The bargains of European negotiators, the accidents of discovery and the convenience of colonial administrations in the end settled the ways in which modernization came to Africa. The suppression of inter-tribal warfare and the introduction of even elementary medical services released population growth in some areas. As in America centuries earlier, the introduction of new crops made it possible to feed more people. Different colonial regimes had different cultural and economic impact, however. Long after the colonialists had gone, there would be big distinctions between countries where, say, French administration or British judicial practice had taken root. All over the continent Africans found new patterns of employment, learnt something of European ways through European schools or service in colonial regiments, saw different things to admire or hate in the white man’s ways which now came to regulate their lives. Even when, as in some British possessions, great emphasis was placed on rule through native institutions, they had henceforth to work in a new context. Tribal and local unities would go on asserting themselves but more and more did so against the grain of new structures created by colonialism and left as a legacy to independent Africa. Christian monogamy, entrepreneurial attitudes, new knowledge (to which the way had been opened by European languages, the most important of all the cultural implants), all contributed finally to a new self-consciousness and greater individualism. From such influences would emerge the new African elites of the twentieth century. Without imperialism, for good or ill, those influences could never have been so effective so fast.

Europe, by contrast, was hardly changed by the African adventure. Clearly, it was important that Europeans could lay their hands on yet more easily exploitable wealth, yet probably only Belgium drew from Africa resources making a real difference to its national future. Sometimes, too, the exploiting of Africa aroused political opposition in European countries; there was more than a touch of the

conquistadores

about some of the late nineteenth-century adventurers. The administration of the Congo by the Belgian King Leopold and forced labour in Portuguese Africa were notorious examples, but there were other places where Africa’s natural resources – human and material – were ruthlessly exploited or despoiled in the interests of profit by Europeans with the connivance of imperial authorities, and this soon created an anti-colonial movement. Some nations recruited African soldiers, though not for service in Europe, where only the French hoped to employ them to offset the weight of German numbers. Some countries hoped for outlets for emigration which would ease social problems,

but the opportunities presented by Africa for European residence were very mixed. There were two large blocks of white settlement in the south, and the British would later open up Kenya and Rhodesia, where there were lands suitable for white farmers. Apart from this, there were the Europeans in the cities of French North Africa, and a growing community of Portuguese planters in Angola. The hopes entertained of Africa as an outlet for Italians, on the other hand, were disappointed, while German immigration was tiny and almost entirely temporary. Some European countries – Russia, Austria, Hungary and the Scandinavian nations – sent virtually no settlers to Africa at all.