The Myth of Nazareth: The Invented Town of Jesus (5 page)

Read The Myth of Nazareth: The Invented Town of Jesus Online

Authors: Rene Salm

Pottery was mass-produced in urban centers even before the Late Bronze Age.

[28]

Ceramic usage and production in satellite villages such as Nazareth generally followed the form, style, and manner of production of the dominant city.

It should be noted that concentrations of people and commercial production activities required large and reliable quantities of water. In urban settlements without perennial water resources cisterns and/or communal reservoirs were cut into the limestone for the collection of rainwater. Some cities also had a planned drainage system and a sewer.

Cities also had a temple. In the Early Bronze Age, Megiddo had several temples within a complex sacred area, with a gigantic circular cult platform upon which animal sacrifices were performed. The need for cooperative building projects such as temples, walls, large cisterns, and for cohesion in times of attack, empowered urban settlements and fostered an allegiance second only to that of family. The earliest urban settlements were, in fact, among kinfolk and an extension of tribal power. The settlement enhanced the identity of the clan, created wealth, and increased prestige. It was greater than the sum total of its individuals. The city was new, marvelous and powerful.

The demise of cities

Before the third millennium ended every city in Palestine either lay in ruins or had been abandoned. We are not sure what caused the vast and auspicious urban experiment to fail, but the failure was complete. Israel Finkelstein speaks of the collapse of fragile “peer-polity systems,” social, political, and commercial webs made up of urban centers, nearby villages, and interrelated rural elements. “The rise of peer-polity systems,” he writes, “creates new perils and instabilities, such as competition for limited resources and attempts at territorial expansion… Due to the interdependence of the entities, such political tensions, or environmental dangers, can bring about the breakdown of the entire system in a short period of time…”

[29]

It is as if mankind, having discovered this marvelous, complex new mode of social organization and source of power, was still too immature to control it. Cities require an enormous investment of energy in subtle, long-range, and unseen elements such as governing, organization, mediation, decision-making, allocation, and planning. For an urban environment to endure, the level of cooperation required of its residents is considerable and unceasing. It may be that the mental apparatus for successful city life had not yet evolved in what was still an essentially tribal society.

Some scholars have suggested that foreign military expeditions destroyed the first cities. We do know that a general deterioration in relations between Egypt and Palestine occurred by mid-millennium and ended trade between these two regions. Thereafter, the towns that continued to prosper in Palestine traded not with Egypt but with Syria.

[30]

A testament from the tomb of the Egyptian general Weni (

c

. 2300 BCE) boasts of his sack and destruction of strongholds in “the land of the sand-dwellers,” which could refer to Palestine. The town of Ai was indeed sacked and burned about 2350, and it remained empty for over a thousand years. On the other hand, the destruction could have come from a very different direction. About this time King Sargon (2340–2284) and/or his grandson Naram-Sin of Akkad invaded Syria, and the cities of Ebla, Ugarit, and Byblos were destroyed. Whether the Akkadians also entered Palestine we do not know.

Another theory is that the cities destroyed one another. “In all sites a number of phases or strata of the period were observed, often separated by conflagration layers testifying to destruction, probably the result of wars.”

[31]

The walls of Jericho were rebuilt or extensively repaired no fewer than sixteen times. All this strife suggests not occasional and distant foes, but perpetual enemies near at hand.

Whatever the reason(s), urban society in the third millennium vanishes before the archaeologist’s eyes. The process was not sudden but gradual. Some sites were abandoned or destroyed early in the millennium (Mezer), never to be rebuilt. Others were forsaken in the middle of the millennium (Gezer, Arad, Tell el-Farah North). Many were abandoned toward the end of the millennium (Beth Shean, Megiddo, Beth Yerah). By 2200 BCE no urban settlements were left in Palestine.

[32]

The Intermediate Period

For two centuries, known as the Intermediate Bronze Age or Intermediate Period (2200–2000),

[33]

the reduced population of Palestine either reverted to nomadism or made use of transient, unfortified settlements. The people were once again hunters, herders, and agriculturalists. Broad areas west of the Jordan River lay uninhabited. Caves resumed an importance held in much earlier times. The short-lived sites from the Intermediate Period that have been identified are small and located in the hill country. Sometimes cemeteries are found, but without traces of habitation—as if people returned regularly to a certain special place to bury their dead. Kathleen Kenyon has shown that bodies were often entombed in a disarticulated state, that is, the bones already jumbled up.

[34]

This is possible if death occurred a considerable time before burial. This in turn suggests that the person died elsewhere and his or her relations carried the remains to the communal burial ground, probably on an annual trip. In the Intermediate Period, the majority of burials at Jericho are of this type, as are those at Megiddo and Tell Ajjul.

Pottery continued to be made, but it is notably poor in quality and pale in color. The ceramics of the Intermediate Period are handmade and often marred by finger marks, dents, and a general lack of polish. Use of the wheel, common in the Early Bronze Age, almost completely ceased. “Apparently the Land of Israel as a whole,” writes Ram Gophna, “became the most backward part of the Levant, a land inhabited only by poor settlements of farmers and herders.”

[35]

Yet the backwardness of Palestine was not unique. Towards the end of the third millennium a series of convulsions seized the entire Near East, accompanied by a period of confusion and universal poverty. In Egypt, the Old Kingdom collapsed about 2130

BCE

. This was followed by two centuries of famine, decentralization, and almost continual violence. The state of anarchy continued from the ninth to the eleventh dynasties until Mentuhotep reunited Egypt at the beginning of the new millennium. In Mesopotamia the Akkadian empire also came to an end, as did the short hegemony of the Gudean dynasty. Finally, the old civilization of Sumer collapsed. The entire Levant experienced two centuries of crisis.

Some scholars, such as Kenyon, consider that a major cause of this wide-ranging dislocation was the incursion of a people known as the Amorites. This nomadic and aggressive tribal people came from the north, captured some cities, and installed itself on the desert fringes of the areas it could not control. For centuries the Amorites were a thorn in the side of even great empires from Egypt to Sumer. They were despised by the “high” civilizations of the urban centers, partly because they lacked cities of their own. Yet the Amorites may not merit such low repute. This resourceful people possessed a creative dynamism that influenced the entire Levant. They were certainly a power to be reckoned with, and may have destroyed many more cities in the Near East than we can prove today. Eventually, Amorites became rulers in Aleppo, Mari, Babylon and Qatna—all centers of great power and civilization.

[36]

As for Palestine, after the utter destruction of the Early Bronze Age there was apparently little left worth ruling. The Amorites on both sides of the Jordan River blended in with the indigenous peoples of the hill country. Invaders in the third millennium, they now constituted a permanent and significant entity. I would suggest that from among their progeny arose the Israelites one thousand years later.

Thus, a conquest of the Holy Land apparently occurred in the third millennium BCE. Is it possible that the “conquest” by the Israelites portrayed in the Bible is approximately one millennium too late? It is becoming increasingly clear that there is little archaeological evidence for such a conquest in the Early Iron Age. If this Amorite-Israelite model is correct, then the Bible preserves dim memories of this early conquest, memories that were long preserved by the victors and that became enshrined in tradition.

The earliest Nazareth evidence

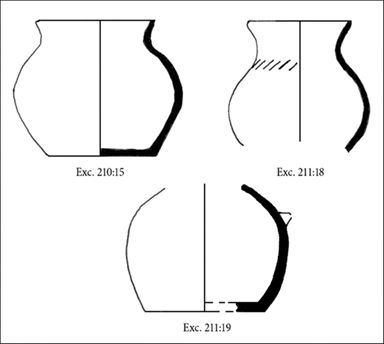

Observation of the vessels by an expert eye reveals an interesting combination technique: the body of the vessel is made by hand, while the neck and rim seem to be wheel made… When both parts of the vessel were ‘leather-hard,’ the potter joined them and smoothed over the join… Incisions of various kinds are generally used in MB I. These are made either with a point or with a three-to-five pronged comb or fork… The decoration is always placed at the base of the neck, and may have been intended to cover the join between the separately made body and neck.

[37]

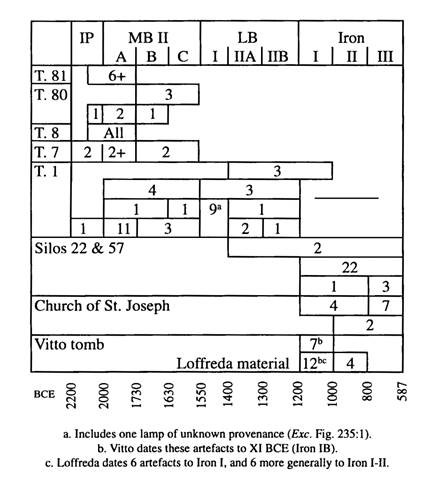

Following these early artefacts, the Nazareth evidence multiplies rapidly and continues through the second millennium. A summary schema of the Bronze and Iron Age evidence (

Illus

.

1.5

) corroborates Bagatti’s overall estimation: “As a general rule, the material found in the three tombs [

i.e.,

Tombs 1, 7, 80] and off and on out of place, brings us to the Middle and Late Bronze, practically from 2000 to 1200, sometimes with some over the limits.”

[38]

Illus.1.4

: The earliest

pottery from the

Nazareth basin.

(Intermediate Period, 2200–2000

BCE).

The Middle and Late Bronze Ages

The second millennium opened with fresh vibrancy and renewed vigor. It is as if the peoples of the Levant had absorbed the foreign energy of the Amorites, and the resultant fusion led to a marvelous renaissance, something wholly new. Cities were reborn. The pottery of the Middle Bronze Age is assured and graceful, exhibiting remarkable inventiveness in form, even playfulness. This is not the work of tense, fearful and impoverished potters, such as we find in the Intermediate Period. MB pottery is relaxed and inspired. After the difficulties of the previous era, one senses that people finally allowed themselves to enjoy life again.

Illus. 1.5: Chronology of the Bronze and Iron Age

Artefacts from Nazareth

The general evidence

The Bronze Age finds at Nazareth come from five tombs and date to the Middle and Late Bronze Ages (2200–1200 BCE).

[39]

Why, we may wonder, was this ancient pottery found only in tombs? The reason is that no excavations from the Nazareth basin have unearthed habitations dating before Byzantine times.

[40]

Nowhere in the basin do we find evidence of pre-Byzantine dwellings, wall foundations, hearths, streets, and the like. The astonishing lack of many kinds of evidence may be partly due to the fact that little of the Nazareth basin has actually been excavated. The principal focus of archaeological attention has been in the venerated compound around the Church of the Annunciation. Comparatively little has been excavated outside this modest area—some scattered tombs dating to various periods, and a few non-funerary sites such as Mary’s Spring (now the Church of St. Gabriel).