The Myth of Nazareth: The Invented Town of Jesus (4 page)

Read The Myth of Nazareth: The Invented Town of Jesus Online

Authors: Rene Salm

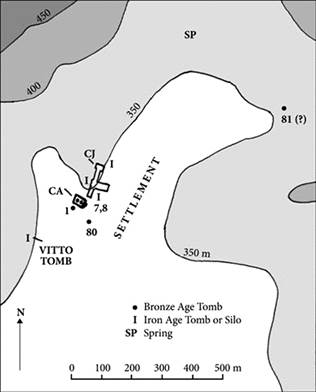

Illus. 1.3

: The Nazareth

basin with Bronze and Iron Age loci.

The venerated sites are included

for reference.

(CA =

Church of the Annunciation. CJ = Church of

St. Joseph.)

Between 1965 and 1979 a second series of excavations was carried out at the Qafza Cave.

[21]

Remains of hominids, known as Proto-Cro-Magnon man, were found dating 120,000 to 80,000 BP. A twenty-year old male, with a child buried at his feet, is the only known example of a double-burial from that long-forgotten era. It became evident that the entrance had served as a burial ground for a very long time. More than a dozen skeletons, as well as numerous Stone Age artefacts, have been unearthed in the Qafza Cave. Thus, the hill is called Har Qedumim (“Mount of the Ancients”). It rises to a height of 386 m and overlooks the Jezreel Valley.

Christian tradition, however, names the hill Jebel Qafza, “Mount of the Leap,” so called because from this hill—according to the Gospel of Luke—the angry Nazarenes attempted to cast Jesus to his death:

And they rose up and put him out of the city, and led him to the brow of the hill on which their city was built, that they might throw him down headlong

(Lk 4:29).

[22]

The most recent evidence from the Qafza Cave dates to 40,000 BP. After that time, no evidence of human presence in the Nazareth area is attested until the beginning of the Bronze Age (

c

. 3,200 BCE). During this long time span Neanderthal man and the giant woolly mammoth became extinct, the glaciers of the most recent ice age receded, and

Homo sapiens

began to organize socially in ways that eventually led to settlement and civilization. He and she learned the rudiments of agriculture, began to domesticate animals, started to use skins for clothing, and learned how to construct dwellings. Humans mastered the use of tools and weapons, including thread and needle, hafted stone and bone implements (that is, affixed to a handle), and bow and arrow. They also became artists, as witnessed by beautiful cave paintings, carved Venus statuettes, and decorated finds. In the late Stone Age we discern the first evidence of religion, with ceremonies, the use of masks, dancing, music, and sacrifice. In short, man and woman became worthy of the appellation

sapiens

. Collective hunting, social stratification, and perhaps even private property came into existence. In this remote past the basis for civilization was laid.

In purely scientific terms, the Cave of the Leap must be reckoned the most important archaeological site in the Nazareth area.

[23]

The hominid bones, tools, and worked objects found there (some over 100,000 years old) are of great scientific value, and of immense intrinsic worth when compared with the fairly ordinary pottery, tombs, and associated artefacts that will be discussed in the following chapters of this series. Nevertheless, the more recent finds assume an importance quite in excess of their intrinsic value—to Christians at any rate—in view of the fact that they decide the central issue of this work: whether the village of Nazareth did or did not exist in the time of Jesus.

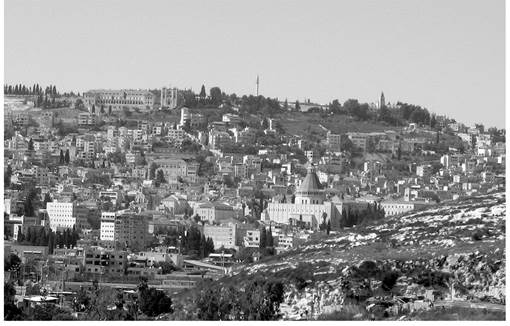

Photograph of the modern town of

Nazareth as viewed from the southeast. The Roman Catholic

Church of the Annunciation is marked by the conical dome just to the right of center.

©BibleWalks.com, used by permission.

The Bronze Age

(To 1200

BCE

)

A warming trend began in the ninth millennium and continued into the eighth. The massive round tower and earliest wall of Jericho, possibly the first urban settlement in the world, date to the eighth millennium. Such precocious urbanization, however, was exceptional. For another five thousand years (

c

. 8000–

c

. 3000) man was a semi-nomad, making use of temporary lodgings for a season, a year, or (more rarely) longer periods of time. Two tendencies co-existed in the Middle East during these millennia between the Stone and Bronze Ages—the peripatetic hunter-gatherer culture, and the sessile farmer-hunter culture. The former predominated, and man was primarily hunter and herder, to a lesser extent farmer and potter.

Slowly, however, humans ceased to wander. The fourth millennium, in particular, witnessed the transition to a settled mode of life. This was the Chalcolithic (literally “copper-stone”) Age, in which humans first mastered metalworking. They continued to move their domiciles for special reasons: to follow the hunt, when the soil was exhausted, or when a site became encumbered with refuse. Yet, they also began to stay in one place the year around, fashioning pottery, farming in season, or sometimes moving on with their flocks and relatives in the winter. Many important cities, including Jerusalem in Judea and Ur in Sumeria, were settled during the Chalcolithic Age.

Though some continued to make use of caves and temporary dwellings, by the end of the fourth millennium many people in the Levant had firmly renounced the peripatetic life known since time immemorial. With that momentous decision came a liberating openness to things new. Change of place gave way to something much more powerful: change in quality of life.

New factors encouraged a sedentary existence, especially domestication of the olive and of the grape. These were the basis for the new Mediterranean diet. Tending of olive trees and vine bushes required, at the minimum, annual return to a place. There is evidence that for a time such annual return was practiced. But it was impractical, given the fickleness of nature and the threat of squatters. Presence on site was required, and with it came ownership and the notion of landed property. Sheep and goats continued to be husbanded, now in the same place that fruit trees were tended. Urbanization was not far behind.

Villagers buried their dead in the ground, sometimes under houses. In Chalcolithic times pits or ‘silos’ were already being used for grain storage. Pottery began already in the sixth millennium, and with the establishment of villages and farming we reach the dawn of history.

Chalcolithic man discovered copper and used it with a sophistication not seen again for thousands of years. In 1961 several hundred metal objects were found at Nahal Mishmar in the Judean desert. This hoard from the fourth millennium contains a panoply of simple and ornate objects—including crowns, scepters, maces, and standards. The objects were made by the lost wax (

cire perdue

) method, “a technique far more sophisticated and complex than simple casting,” writes Rivka Gonen. “The end of the Chalcolithic period signaled the end of a golden age of metallurgy.”

[24]

The Early Bronze Age

When did settlement in the Nazareth valley begin? We can answer this question by examining the evidence from the basin and also by looking at settlement patterns in the area. We shall consider the general region first. In 1990–91 the University of Haifa conducted an archaeological survey of the Nazareth-Afula area and identified fifteen sites inhabited in the Early Bronze Age.

[25]

Afula is a village ten kilometers south of Nazareth, and like several other settlements in the Jezreel Valley it was already inhabited by the middle of the third millennium. In that era, urbanization was wedded to the new Mediterranean economy of pasturing, agriculture, oil production, and viniculture. In the Early Bronze Age the art of producing olive oil developed, and Egyptian records dating as far back as 2500 BCE refer to the use of grapes for making wine.

The welfare of the rural areas was intimately linked with that of the major towns. “The rise of Megiddo,” writes Israel Finkelstein, “was coupled with prosperity in the entire Jezreel Valley: the important [neighboring] sites of Taanach, Yokneam, Affula, Jezreel and Beth-shan were founded, or grew in importance, in the EB III” (2650–2350 BCE).

[26]

Every valley in Palestine had its dominant city (or cities). Each urban center provided a market for the goods produced in the surrounding area, a central depot for trade, specialists and craftspeople, defensive walls, and organized protection in times of attack. Finkelstein divides Palestine into eleven major regions in the EB, each dominated by a major town in symbiotic relationship with many subsidiary villages. Urban, semi-urban, and non-urban populations cooperated for the first time, and specialization emerged. The improved quality of pottery, with thinner walls and higher firing temperatures, suggests the development of a dedicated class of artisans and workshops which served an entire region. The success of the Mediterranean economy also led to a dramatic increase in the need to transport oil and wine. The introduction of the potter’s wheel in the mid-third millennium met this need and vastly increased the number of vessels produced. As the millennium progressed, the proportion of wheel-made vessels increased steadily, along with affluence and population growth.

Communication and trade were long-range and probably more extensive than we suspect. For example, an impressive hoard of metal objects was found at Kfar Monash along the coastal trade route. It dates to the third millennium and contains raw material from the Sinai, Syria, Anatolia, and Armenia, attesting to contemporary contact with those remote places. Amnon Ben-Tor notes that Beth Yerah ware, a ceramic style dating to the middle of the third millennium, had its roots as far away as South Russia.

[27]

Palestine exported oil, wine, and date honey in large jars, while cosmetics (scented oils), resins (for sealing and embalming), bitumen (for caulking rafts, baskets, and monuments), and higher-quality substances were transported in smaller jugs. Interestingly, trade went overland because, as opposed to Syria, until the second millennium Palestine had no coastal ports.

With the rise of permanent settlements in the Early Bronze Age came many new challenges. Settlements needed to be organized, governed and defended. This demanded a degree of planning, specialization, and cooperation not known before. For defensive reasons, villages were generally established on promontories or high places. Many towns without walls in the first part of the Early Bronze Age had acquired impressive fortifications by the middle of the millennium. The wall of Megiddo was over eight meters (26 ft.) thick. Such massive walls were evidently not built to counter battering rams, which were not yet invented, but to hinder sapping. Their great width also allowed many men to be stationed atop, aiding in defense and preventing scaling.

As mentioned above, Megiddo was arguably the most important town in Northern Palestine in pre-Exilic times. It has been the object of several archaeological expeditions and has been well studied. Because this city dominated the region in which Nazareth is located—economically, militarily, and culturally—it furnishes an important reference point in our discussion of Nazareth archaeology. Twenty strata have been excavated (

pre-70

Appendix 3

). Father Bagatti, the principal archaeologist of Nazareth, makes frequent typological comparisons between the pottery of Nazareth and that of Megiddo (

Appendices 1

and

2

). In the latter were numerous workshops which supplied the surrounding area with wares:

The most extensive pottery

workshop area yet found in Palestine is on the east slope of the Megiddo

mound. As at

Lachish, the Megiddo ceramicists set up their shops in the various caves

that dot the hillside. This was a cemetery area in antiquity—a common place to find pottery workshops… At least 12

kilns

were found… Although it is difficult to date the period of use of the various potters’ caves with certainty, the associated pottery indicates that they were in use in the Late Bronze and Iron Ages. [Wood/41]