The Myth of Nazareth: The Invented Town of Jesus (3 page)

Read The Myth of Nazareth: The Invented Town of Jesus Online

Authors: Rene Salm

Fortunately, in recent decades the Catholic reports have been supplemented by a number of studies written principally by Israeli specialists. They deal with tombs outside the Franciscan property, and also have redated many of the artefacts first published by Bagatti. Until

The Myth of Nazareth

, these independent studies have not been incorporated into the overall assessment of the site. This book brings together all the primary reports for the first time, and allows an independent and objective opinion to be formed regarding the site’s history. Some of the ancillary reports are quite obscure and have never been translated into English. At least one was at the time of this writing unavailable in the U.S.A. In all, the sources span half a dozen modern languages. It is of course possible that one or two brief reports may have eluded my gaze, and I am mindful that excavations and discoveries continue in Nazareth. Yet I am confident that new results will support the conclusions of this study. The score of primary reports used in

The Myth of Nazareth

, encompassing both traditional and non-traditional sources, represent the essential results of excavations that span over a century. Their combined verdict will not be overturned by an overlooked shard.

The argument of

The Myth of Nazareth

presumably qualifies as “real knowledge… of an objective, external world that can be perceived by the human senses,” in the words of one prominent American archaeologist.

[5]

Yet, those who seek to demonstrate the hand of God in human affairs and in holy writ will be sorely disappointed in these pages, whose facts accord neither with tradition nor with scripture. The anchor of biblical inerrantism must be hoisted, that the ship of free inquiry may finally sail unfettered. For some this is too much freedom, tantamount to being cut adrift in a sea of godless relativism. They prefer to view tradition as the natural repository of all that is worthy of serious consideration. And tradition maintains that man’s history is ordained and guided from on high, and a divine plan infuses the cosmos. The sun rises every morning and sets every evening,

and God is in his heaven

, taking an interest in us, benevolently watching and sustaining the universe.

We are not alone. These are the sentiments of the traditionalist who fears change and who will fashion an anchor—any anchor—against the engulfing chaos of life. If that anchor is imagined, so be it. To the traditional believer it is real, and that makes it efficacious.

The real battle, however, is not empirical, nor even about how we view the evidence of Nazareth or of any other site in biblical archaeology. The battle is not between postmodernists and conservatives, minimalists and maximalists, nihilists and positivists. It has nothing to do with facts but has to do with human needs,

for if need be, man will invent

. He desires comfort, not facts. The two thousand years of Christian tradition have nothing to do with the facts of history. They never did. They have to do with human desires and needs.

The incipience of “Nazareth” in the gospels, textual and literary considerations, the motives behind its invention, and some consequences of that invention, will be taken up in a second volume,

A New Account of Christian Origins

. Together, these publications reflect recent scholarly scepticism concerning traditional views of Jesus, the gospels, and early Christianity. Based on a non-doctrinal view of the primary sources,

A New Account

considers the disparate views of so-called “heretical” writings on a par with those in the New Testament canon. It uses the scientific tools developed by modern theological research to arrive at a wholistic and historically accurate portrait of early Christianity.

A battle has raged over the Nazareth evidence from ancient times, ever since problematic claims were made about the town. That which is problematic must be doubly defended, and it is not coincidence that the myth of Nazareth has needed hiding under a thick blanket of tradition. Remoteness confers safety, which is one reason Christian scripture was elevated to unquestioned status and placed out of the reach of ordinary inquiry. Yet, the questions raised by objective inquiry must be answered if one is to understand the complex beginnings of Christianity.

The Myth of Nazareth

is one element of that inquiry. The repercussions of the resulting reassessment of the gospel record upon the traditional interpretation of Christian origins can hardly be exaggerated.

In this new millennium, the historical basis of Christian belief is being investigated in ways unimagined only a few generations ago. Abject veneration is finally yielding to free inquiry, allowing us to approach and see what tradition has solicitously protected for two thousand years. Let us peel back the blanket and look. Perhaps nothing is there at all.

Chapter One

The Stone, Bronze, and Iron Ages

The Nazareth basin

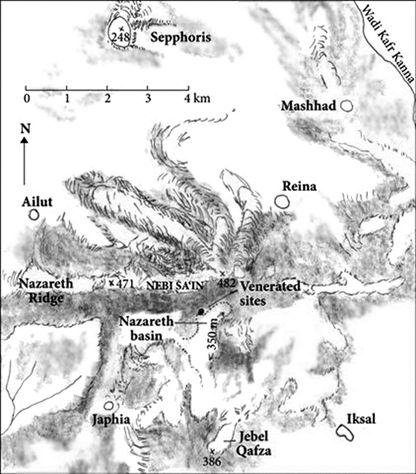

Nazareth lies in the hills of Lower Galilee, approximately equidistant from the Mediterranean Sea and the Sea of Galilee. The Nazareth Range, in which it lies, is the southernmost of several parallel east-west ranges that characterize the elevated tableau of Lower Galilee.

[6]

Both the wide and fertile Jezreel Valley to the south, as well as the Tir‘an valley to the north were major conduits for trade in antiquity, linking the two major north-south routes that traversed the Holy Land: the

Via Maris

, or “Way of the Sea,”

[7]

and the more inland Ridge Route (

Illus 1.1

). The more southerly route ran from Megiddo to Beth Shan, while the route through the Tir‘an Valley (the Trunk Road or Caravan Route)

[8]

connected Akko on the coast with the Sea of Galilee in the east.

Yet, though trade routes passed within a few kilometers of the site, ancient Nazareth was separated from them by hills. It sat in a small basin, valley, or plateau (all these words are used to describe it) about two kilometers long and scarcely one kilometer wide (

Illus. 1.2

). The basin is oriented north-south. Its floor is 320 meters above sea level, and the area below the 350 m contour line is about 400 acres (162 hectares).

[9]

This expansive area furnished many possible sites for habitation.

The backbone of the Nazareth Range, known as the Nazareth Ridge, runs east-west and forms the steep northern side of the basin. It divides the watershed of the Tir‘an Valley from that of the Jezreel Valley, rising to several modest summits at the Nazareth basin. These heights are collectively called the Jebel Nebi Sa‘in.

[10]

Its peak of 495 meters (1,624 ft.) interposes itself on a line between the basin and the onetime settlement of Sepphoris, six kilometers to the north. To the west and east of this summit the Nebi Sa‘in reaches somewhat lesser peaks of 471 and 482 meters respectively.

[11]

Illus

. 1.1. Palestine and its principal trade routes

Though not particularly high, the Nazareth Ridge forms a physical divide. Lying to the south of this ridge, the Nazareth basin is naturally oriented towards the Jezreel Valley to its south, and not to the north. This fact must be taken into account when considering the history of the basin in successive epochs. Jezreel Valley, a scant 2 km from the southern edge of the Nazareth basin. Just 17 km to the southwest was the fortress of Megiddo, the most important town in the Jezreel Valley in Bronze and Iron Age times. Megiddo was located on the Via Maris at the mouth of the Wadi ‘Ara, the narrow pass traversing the Carmel Range. Thus, it commanded both the Via Maris and the Jezreel Valley. Auspiciously situated, hilltop Megiddo (Har-Megiddo, from whose name we derive Armageddon) was the focus of continual military designs, alternately ruled by Egypt, Syria, and Mesopotamia. It was splendidly defensible and fortuitously watered by several springs. For millennia, from about 3100 BCE to the seventh century BCE, Megiddo fed a number of satellite villages in the broad Jezreel Valley, over which it held sway like a queen over her courtiers. The city has been well studied,

[12]

and offers an excellent compass by which to orient proximate finds in the Nazareth basin which fell within its zone of influence.

[13]

The Nazareth Range is approximately 15 km long and 5 km at it widest point. It is primarily an Eocene limestone, whose softness is conducive to pitting and to being worked by human hands. More than sixty underground hollows have been identified in the vicinity of the Church of the Annunciation, the area generally referred to as the “venerated sites” or “venerated area.” The Church of the Annunciation (CA) has been the principal focus of pilgrimage and also of excavations carried out in Nazareth. The venerated area is quite modest in size, encompassing approximately 100 m by 60 m. The modern Church of the Annunciation is at the southern end and the Church of St. Joseph at the northern end. In the roughly 100 meters between the two churches lies the Franciscan convent (see

Illus

. 1.3.)

[14]

The venerated area has been owned by the Franciscans since 1620.

[15]

There is one year-round spring in the Nazareth valley, known as Mary’s Spring (Ain Maryam). It is located at the northeastern tip of the basin.

[16]

Today, the spring is under the Greek Orthodox Church of St. Gabriel, and its waters are piped a few hundred feet downhill to Mary’s Well, readily accessible to the townspeople. Nazareth lies in the territory traditionally allotted to the tribe of Zebulun.

[17]

No settlement of Nazareth is mentioned in Jewish scripture, though Japhia occurs once (at Josh. 19:12).

[18]

In contrast to the drier southern and eastern parts of Palestine, Lower Galilee receives abundant rainfall, sufficient for good crops and pasture.

[19]

The Nazareth basin’s removed location was conducive to a peaceful life, and its temperate climate and physical attributes accommodated an economy of agriculture and pasturing.

Illus. 1.2

: The

Nazareth Range.

The Stone Age

(

c

. 600,000 –

c

. 4,500 BCE)

Stone Age

Chronology

Pre-Paleolithic

4,000,000 BP “Lucy,” early hominids in East Africa.

2,000,000–600,000 Eolithic Period: earliest tools; evolution towards

true

Homo sapiens

.

Paleolithic

600,000–120,000 Lower Paleolithic: Dispersion of humans.

120,000–35,000 Middle Paleolithic: Neanderthals in Europe and Near East.

35,000–10,000 Upper Paleolithic: Cro-Magnon (truly human).

Post-Paleolithic

10,000 BCE Mesolithic: first hints of agriculture.

8300 Pre-Pottery Neolithic A:

true agriculture in the Near

East; domestication of animals; incipient villages.

7300 Pre-Pottery Neolithic B.

6000 Pottery Neolithic A. Copper first begins to be smelted.

5000 Pottery Neolithic B (Early Chalcolithic).

3800–3100 Chalcolithic: metallurgy and pottery. By 2800 the working of bronze is widespread.

The Cave of the Leap

In 1933 René Neuville, the French Vice-consul to Palestine, learned of an interesting cave at the northern edge of the Jezreel Valley, on the side of the mountain called the Jebel Qafza two kilometers south of the Nazareth basin. The following year Neuville, an archaeologist himself, excavated the cave together with a colleague from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. They uncovered two skulls dating 40,000 years BP, corresponding to the Fourth (Würm) Glacial Period. Astonished, the archaeologists dug deeper and unearthed numerous Paleolithic tools. These were of the Mousterian culture, typically associated with Neanderthal Man (

fl

. 85,000–35,000 BP). Continuing to dig, they discovered the most prized finds of all—four hominid skulls, each far older than Neanderthal Man. Artefacts from this deep layer had Levallois flaking techniques (100,000+ BP).

[20]

In sum, this cave contains the earliest evidence of habitation in the Nazareth area, and represents one of the oldest caves in Palestine used by humans.