The Making Of The British Army (6 page)

Read The Making Of The British Army Online

Authors: Allan Mallinson

Far from being a winter’s march by which the army was almost broken, indeed, it was a march by which – almost literally – the British army was made.

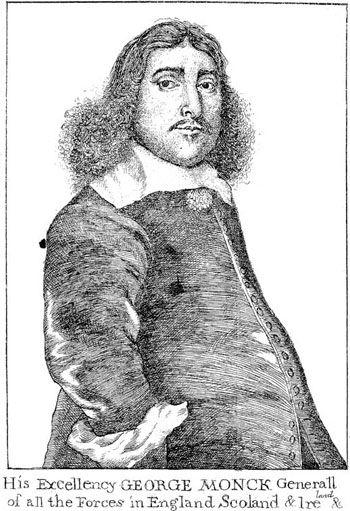

If not the father of the British Army, then certainly the midwife.

Blackheath, south-east London, 29 May 1660

THE KING’S THIRTIETH BIRTHDAY WAS THEATRE AS GOOD AS ANY MONARCH OF

the

ancien régime

could have wished for. Charles Stuart, as still he was officially known, had stepped on to English soil – or, rather shingle – four days earlier for the first time in nearly a decade, and now he rode ceremoniously on to the ‘bleak heath’, which since Roman times had served as a marching camp, to take possession of England’s army. At Dover he had knelt momentarily and thankfully on the beach, to be greeted as he rose by Monck, and from there had made his steady progress via Canterbury. Having knighted the former Roundhead general in the dilapidated cathedral he rode on through cheering crowds in the lanes of Kent to this vast and grassy parade ground where 30,000 troops, with Monck at their head, waited to salute their new sovereign. The sun shone, although the silence must have seemed at least a trifle forbidding to Charles, for most of these men had fought his father in the war. Some might even have connived at his execution.

‘You had none of these at Coldstream,’ muttered one of Monck’s officers as the glittering royal party came on parade. ‘But grasshoppers and butterflies never come abroad in frosty weather!’

Charles did indeed cut a fine figure – tall, ‘black and very slender-faced’, in a doublet of silver cloth, a cloak decorated with gold lace, and a hat with a plume of red feathers. And his brothers the duke of York

and duke of Gloucester were hardly less gorgeously arrayed. Three men in their prime, the very image of Cavaliers, and behind them the Life Guard of eighty troopers, ‘gentlemen’s sons’ as Cromwell had dubbed them ruefully – exiles all, and as glad to see their native country again as was the King himself. Paradise lost, and now regained.

Sir George Monck, made captain-general by Parliament after his march from Coldstream, broke silence with the command to ‘Take heed and pay attention to what you hear!’

The ranks of the former New Model Army braced as he read out a declaration of loyalty to His Majesty on their behalf.

At the signal, pikemen and musketeers gave loud cheers, raised their hats and their weapons, and shouted, ‘God save King Charles the Second!’

Monck silenced them as swiftly with a hand held high. ‘Lay down your arms!’

Thirty thousand men in the pay of the Commonwealth bent the knee and laid down musket and pike.

‘Retire!’

They turned about, marched a few token paces, halted, and faced front once more.

‘To your arms!’

Drums beat as each pikeman and musketeer ran to his mark.

‘In the name of King Charles the Second, take up your arms, shoulder your matchlocks and advance your spears!’

Again they bent the knee; and took up musket and pike as soldiers of the King.

If there was a precise moment when the British army was formed, this was it, marked (though not with this purpose in mind) by this highly symbolic act. Yet it goes unheeded today except by the in-pensioners of the Royal Hospital at Chelsea, who celebrate each year the return of the King, parading with sprigs of oak leaves in their hats to commemorate Charles’s escape after the battle of Worcester, when he hid in an oak tree, the ‘Royal Oak’, in the grounds of Boscobel house in Staffordshire. ‘Oakapple Day’ is founder’s day at Chelsea, and the nearest that any in the Queen’s uniform come to celebrating the founding of the army itself.

11

But Monck’s 30,000 were vastly more than the King needed. Indeed, they were vastly more than Parliament (even a Cavalier parliament) was willing to pay for. Honourable Members had intended the return of the King, but also of the

status quo ante –

the position before Charles’s father had dismissed Parliament and tried personal rule. They had no wish now to provide the new King with the means to coerce them out of the power they had earlier wrested from the Crown. The army was therefore to be disbanded. And at once.

It would at least, and at last, be paid. Parliament had voted two-thirds of the arrears (which amounted to the impressively precise sum of £835,819 8s 10d

12

– testimony to the diligence with which the pay serjeants even then did their work), and Charles would find the balance.

But some soldiers there would still have to be: the monarch needed close protection, and there were coastal forts to be garrisoned. Two regiments would therefore be retained as well as the garrisons: the King’s Life Guard, and Monck’s regiment of ‘Coldstreamers’, which Charles creatively called his ‘guards’ to circumvent Parliament’s objections to a standing force. Otherwise there was to be a return to former practice: if need arose for an army (as all prayed it would not), the militia would provide – the sort of men who had stood at Edgehill ‘in the same garments in which they left their native fields; and with scythes, pitchforks, and even sickles in their hands’. That scratch forces had proved no use to either side in the late war was conveniently forgotten. In Scotland, too, there was retrenchment. Now a separate polity again, released from Cromwell’s forced integration with the Commonwealth, it retained only Lord George Douglas’s Regiment, which had been raised in 1633 for service with the French – Les Royal Écossais – and had served continuously abroad. Other regiments transferred

en bloc

to the Portuguese service for the war of independence from Spain.

Parliament’s hopes for better (and cheaper) times soon proved delusory, however. In the autumn and winter several conspiracies came to light. Charles and his commander-in-chief the duke of Albemarle, as Monck was now styled, were therefore able to convince Parliament that a larger body of guards was needed to guarantee law and order. A permanent establishment of four regiments was duly authorized at a cost of £122,407 15s 10d a year, roughly 10 per cent of the annual supply

voted to the Crown. And so the army came into official being (though it had never actually disbanded) by Royal Warrant on 26 January 1661, consisting of: the King’s Regiment of Horse Guards (later called simply the Life Guards); the King’s Regiment of Horse (later the Royal Horse Guards, or ‘Blues’), formed from Cromwell’s old Life Guard of Horse; the 1st Regiment of Foot Guards (after Waterloo called the Grenadier Guards), formed from Lord Wentworth’s Regiment, which had been raised at Bruges in the Spanish Netherlands as bodyguard to Charles in exile; and Monck’s own regiment of Coldstreamers, the Lord General’s Regiment of Foot Guards (after Monck’s death in 1670 called simply the Coldstream Guards).

13

These were all to be stationed in London. Around the country in addition were some twenty-eight garrisons of various sizes, none of them large – a sort of nascent Territorial Army – at a further cost of £67,316 15s 6d a year. The small but longstanding garrisons in the West Indies and North America were to be financed largely by local taxes; and the Irish establishment remained entirely separate. To tide things over while these new arrangements were put in place, Lord George Douglas’s Regiment of Royal Scots was brought to England from France.

Charles and Monck had thereby laid the foundations of today’s regimental system, and on these there would now be steady and continuous building. In 1661 Charles contracted a marriage with the Infanta Catarina (Catherine of Braganza), second surviving daughter of John IV of Portugal. Her dowry included sugar, a deal of plate and jewels, bills of exchange worth £20 million in today’s terms, the rights to free trade with Brazil and the East Indies, and the port-colonies of Bombay and Tangier. Bombay was a prospering trading post, needing a mere 400 men to secure it (Charles sold it to the East India Company a few years later), but Tangier was a different prospect. It held a strategic position at the entry to the Mediterranean, constantly menaced by Moors and Barbary pirates, and needed an altogether bigger garrison – the ‘Tangier Regiment of Horse’ and a regiment of foot which Charles was soon speaking of as ‘Our Dearest Consort’s, the Queen’s Regiment’.

Still Parliament was content enough, for only the Guards were seen in the streets. The unregimented garrisons were tied to their forts, the foreign garrisons were largely self-financing, and the few regiments

such as Douglas’s were in effect mercenaries, paid for by the French, the Dutch or the Portuguese, although those in the French service were suspected of being a closet Royalist reserve for nefarious purposes – perhaps for coercing Parliament, or bringing back Catholicism. Events soon began to bring many of these ‘foreign’ troops home, however. When the Second Anglo-Dutch War broke out in 1664 the English regiments of the Anglo-Dutch Brigade quit Flanders for London and were at once re-formed as a third regiment of foot, called the Holland Regiment; other soldiers were taken into the Admiralty Regiment,

14

which later became the Royal Marines. A third Dutch War (1672–4), in which England joined the French in a costly attack on the United Provinces,

15

came to an abrupt end at the insistence of Parliament, alarmed not least by the expense, and consequently the Anglo-French Brigade was dissolved and its men re-enlisted in the regiments at home (Lord George Douglas’s Regiment, the Royal Scots, were brought officially on to the English establishment in 1678).

16

The regimental acquittance rolls must have been a nightmare for the pay serjeants.

And then in 1684, the year before his death, Charles at last abandoned his dear consort’s troublesome and expensive dowry, Tangier, and so the home establishment gained a further – fourth – regiment of foot (renamed the Duchess of York and Albany’s Regiment, later the King’s Own) and a third of cavalry – or rather, mounted infantry, for the Tangier Horse were re-designated the Royal Dragoons. In Scotland, too, there were changes. Charles’s forces north of the border were always few – never more than 3,000 – but there was a notable birth, a regiment of dragoons known later as the Scots Greys, and known better still today, musically at least, as the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards.

17

In Ireland, unusually, there was peace, except that, being Ireland, it was a peace with constant breaches requiring an active constabulary. At the Restoration the Cromwellian garrison there had immediately declared for the King and quietly acquiesced in a severe reduction that left about 7,500 men in tiny, scattered posts, unregimented till 1672. It was a largely Protestant army, neglected, in arrears of pay, and miserable in their alien barracks. Catholics engaged instead for foreign service, later coming to be known as the ‘Wild Geese’, though occasionally they found themselves serving under unexpected orders – as, for example, when the Third Dutch War ended and Viscount Clare’s regiment of infantry transferred from the Stadtholder’s service to the English establishment as the 5th Foot.

By the time of Charles’s death, therefore, in the curious, haphazard way that the regimental system continues to develop even today, there had grown up an English standing force (army is perhaps too grand a description) that had no common system of organization or drill, but plenty of fighting experience. And varied fighting at that, from ‘continental warfare’ (sieges, counter-sieges and field battles) learned under the great French marshal Turenne and the impressive Dutch general Schomberg to the wholly irregular warfare of Tangier. England was becoming accustomed to the fact of a standing army ‘in time of peace’, even if in law it did not exist.