The Making Of The British Army (10 page)

Read The Making Of The British Army Online

Authors: Allan Mallinson

To begin with, the army had grown to an unprecedented size. In addition to the ‘guards and garrisons’ at home and in Ireland, from 1702 Britain’s treaty contribution to the Grand Alliance was 40,000 men, of whom half were to be ‘subject troops’ – men raised within the kingdom(s) – and the rest hired from continental princes. Later there was ‘the Augmentation’ – 20,000 men, a third of them subject troops, half the bill footed by the Dutch. Eventually Marlborough would have more than 30,000 red-coated subject troops at his disposal in the Low Countries. Nor were British eyes directed only to the south-east; from 1707 Britain would take the fight to the Bourbon Philip V, the French placeman on the Spanish throne, and there would be almost as many redcoats in Portugal and Spain.

This fourfold increase in the post-Ryswick figure could not have been achieved without the proprietor-colonel system in which some notable – a man of standing in the county, but not necessarily with military experience – would be contracted to field a regiment of specified strength. In 1704 an infantry battalion comprised some 800 men organized in twelve ‘battalion companies’ of sixty, and one grenadier company of seventy. They were equipped by the Board of Ordnance but clothed, fed and paid by the colonel. His return was his own pay, which was not great, plus any legitimate surplus from the public money he was given for the maintenance of his regiment. Day to day, the regiment was commanded and trained by a lieutenant-colonel. And since the proprietor-colonel frequently had other interests such as offices of state or, on campaign, a superior appointment (command of a brigade or a position on the staff), the lieutenant-colonel usually commanded on operations too. Charles Churchill, Marlborough’s brother, by now a lieutenant-general and a key member of the duke’s high command, was still colonel of the 3rd Foot, a regiment with which, though it was to fight at Blenheim, he had only the most perfunctory contact. Most of his proprietorial interest would have been handled by a London agent, a figure who would grow in importance to the whole system of army administration. The lieutenant-colonel, the major (the lieutenant-colonel’s second-in-command) and the company officers (a captain assisted by two or three ensigns) bought their commissions from the Crown but were paid direct by the agents on the Crown’s behalf. Officers were able to buy and sell their commissions more or less at will, and this became big business for the agents. Purchase was in fact the usual route to promotion to the next rank up, although commissioning and promotion without payment was sometimes conferred for men with the right connections, or for distinguished service.

The origins of ‘purchase’ (the whole system of buying and selling of commissions) are uncertain, but throughout Europe in the Middle Ages mercenary troops were raised on the expectation not of pay but of profit; not just of booty but of legitimate trading in the wake of conquest. Those who wished to hazard for profit in this way were expected, in effect, to buy a share in the undertaking, and since the profit was shared out among the various ranks pro rata, it followed that the price of each rank – each ‘share’ – would be different. The term ‘company’ for such a body of mercenaries possibly derives from this

military – mercantile arrangement. Bearing in mind the Crown’s penury after the Restoration, purchase was a useful additional source of income to fund the unconstitutional army. In effect, therefore, an officer purchased an annuity, though he could always recover his original investment by ‘selling out’. If he wished to purchase a greater annuity – if he wished for higher rank – all he had to do was pay the difference between the price of the higher rank and his own, as long as there was a vacancy in the higher rank. If his own regiment had no vacancy the aspiring officer would have to buy into a regiment that did, and regimental mobility was a feature of the British army until late in the nineteenth century, when purchase was abolished.

Those who could not afford to purchase promotion had to put their faith in the fortunes of war, slow and unpredictable as they were. If an officer died on active service, his commission was forfeit to the Crown. The next senior officer was promoted in his place without payment, which in turn created another vacancy, and so on down the ranks to the lowest, where seniority on the list told. This gave rise to the black-humoured toast ‘To a bloody war, and a sickly season!’ If purchase seems incomprehensible as a concept today, it is as well to remember that almost every public office in Stuart times was obtained in this way. Even William Blathwayt had paid for his post as secretary at war.

One exception was general officers, those beyond the ‘field’ ranks (as the regimental officers, captain to colonel, were known). Whereas field officers purchased their commissions at a remove through agents, generals were appointed personally by the Crown. And while it was not always undiluted merit that determined promotion to general rank, money did not change hands. Generals were concerned with the direction of campaigns and battles and with their logistic arrangements. In the Middle Ages and ‘early modern period’ men of proven worth were appointed to senior command on campaign in an ad hoc fashion: there was no permanent establishment of generals, the rank being frequently honorific. Regiments were ‘brigaded’ – grouped in brigades, the term that superseded ‘tertia’ after the Civil War – and commanded by the senior regimental commander. The ‘brigadier’ had no formally allotted staff, only the officers he chose from his own regiment to relay his orders in battle, for he was not administratively responsible for the regiments in his brigade, only for their actual control during the fighting. But by 1704 these arrangements were becoming more formalized, though brigades were still not permanent

commands. The rank of brigadier-general had come into use, but it was a temporary one given to the senior officer within the equally temporary grouping of regiments. Indeed, a brigade might be commanded by a major-general if that was the rank of the senior ‘proprietor-colonel’,

27

though he was still referred to (confusingly to modern ears) as ‘brigadier’. Thus Colonel Archibald Rowe of the Scots Fuzileers, a proprietor-colonel who actually took his regiment into the field, was appointed to command one of the three brigades at Blenheim as Brigadier-General Rowe, while a second brigade was commanded by Major-General James Hamilton (earl of Orkney), colonel of the 1st Foot (Royal Scots), and a third by Major-General James Ferguson, colonel of the 26th (the Cameronians). All three led the brigades in which their own regiments were mustered, these regiments being commanded in their absence by the lieutenant-colonel. There were no ‘divisions’ – groupings of brigades – at this time: brigades were mustered into ‘columns’, usually for administrative and security purposes on the march, although just occasionally – as at Blenheim – divisions were employed as entities for battle itself.

28

Altogether then, Marlborough’s army marching along the Danube was a far more professional affair than any fielded before by Britain. Crucially the infantry, with the shorter and lighter flintlock musket (not needing a ‘rest’ on which to lay the barrel to take aim) and socket bayonet, were a great deal handier than their predecessors with whom William had made war in Flanders only a decade earlier. The flintlock’s calibre was also smaller than the matchlock’s and the ball therefore lighter, while no less lethal, allowing the infantryman to carry more rounds. The new weapon simply permitted a greater rate of fire. At Edgehill it had been one round in two minutes; now it was three or even four a minute in the best-drilled regiments.

And Marlborough had made sure this innovation was exploited to the utmost. Fifteen years earlier, when first appointed to command the army in Flanders, he had written to the secretary at war, Blathwayt, to ‘desire that you will know the King’s pleasure whether he will have the

Regiments of Foot learn the Duch

[sic]

exercise, or else to continue the English, for if he will I must have it translated into English’. What he meant was the standardization of volley fire, for the practice had generally been for each rank (perhaps two companies in line – up to 200 men) to fire as a single entity, with the rank behind firing the next volley while the first rank reloaded, and so on. Since this involved ‘dressing’ (the realignment of the rank about to fire after it had stepped forward of the previous front rank) there was inevitably a hiatus between volleys. In Marlborough’s ‘Duch system’, however, the companies were subdivided into ‘platoons’, each firing independently, so that a rolling fire could be kept up.

29

Musketry was now therefore a decisive force on the battlefield, where before it had been more often than not a hazard, an irritant, and secondary to the

arme blanche

, as the knightly sword and lance or the ‘puissant pike’ were known. The British infantry became hugely adept at this system of fire control: time after time their disciplined volleys won the day in Marlborough’s battles. And they would continue the ascendancy in the later continental wars of the eighteenth century – and then most spectacularly of all at the hands of that master of the tactical battle, the duke of Wellington. Tight, platoon-based fire control is still today the hallmark of the British infantry. Its deep-seated importance in the collective subconscious of the army is demonstrated in the annual Queen’s birthday parade on Horse Guards (‘Trooping the Colour’), for the drill evolutions through which the Foot Guards are put in that magnificent hour – sharp, precise, emphatic – are the relict of the battlefield drill that got the serried ranks of infantrymen to deliver volleys in whichever direction was needed and in the shortest possible time. No other troops in the world save those of the old Commonwealth look like the British on parade, for their drill comes from a different period and purpose.

30

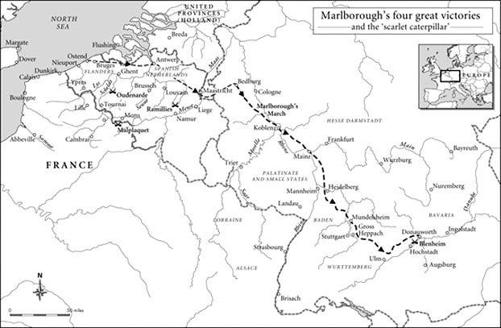

By 1704 the War of the Spanish Succession was in its fourth year. Marlborough had achieved much, but in strategic terms it had been

inconclusive. Indeed, the year before had been one of consistent success for France and her allies, particularly on the Danube. Vienna itself was now within French grasp, and the Austrian and Imperial capital’s fall would no doubt be followed by the collapse of the Grand Alliance. To hasten it, Marshal Tallard’s army of 50,000 were to strike out from Strasbourg (then in French territory) and east along the Danube, while 46,000 Frenchmen under Marshal Villeroi kept the Anglo-Dutch army pinned down at Maastricht. Which left only Prince Louis of Baden’s force of 36,000 in the Lines of Stollhofen 30 miles north-east of Strasbourg, and a much smaller force at Ulm, standing in the way of Tallard’s march on Vienna.

John Churchill, first duke of Marlborough, ‘Captain-General of Her Majesty’s Armies at Home and Abroad’.

On learning of this, Marlborough at once saw the imperative. His most recent biographer, Professor Richard Holmes, quotes Clausewitz writing a century and more later that in a coalition war the very cohesion of the coalition is of fundamental importance. Holmes goes on to say that ‘Marlborough was, first to last, a coalition general, supremely skilled at holding the Grand Alliance together’. And holding the alliance together now meant that Marlborough had to prevent the fall of Vienna. But the problem was the Dutch: they would simply not let the allied army quit the Spanish Netherlands to march deep into Bavaria. So he devised a ruse, disguising his purpose from The Hague and Versailles alike. His intentions, he wrote to London in late April, were

to march with the English to Coblenz and declare that I intend to campaign on the Moselle. But when I come there, to write to the Dutch States that I think it absolutely necessary for the saving of the Empire to march with the troops under my command and to join with those that are in Germany … in order to make measures with Prince Lewis of Baden for the speedy reduction of the Elector of Bavaria.

31