The Making Of The British Army (3 page)

Read The Making Of The British Army Online

Authors: Allan Mallinson

People tell academics and clergy to look at what the ‘real world’ is like. By this they mean dictating letters, selling and buying shares, instituting manufacturing processes, tapping information into computers. But behind their world is the real world they have forgotten: the battlefield. Here is the ultimate reason of the social order written in letters of lead and shards of steel.

The Making of the British Army

is about the battlefield, the place where, ultimately, the peace of ‘the social order’ is decided: and it is indeed written in letters of lead and shards of steel.

Edgehill, 23 October 1642

ROBERT BERTIE, EARL OF LINDSEY, LAY IN AGONY ON A PILE OF STRAW WHILE

his son, Lord Willoughby de Eresby, tried to staunch the flow of blood. Veteran of many a battle on the Continent, the earl was now a year short of sixty, bald and gaunt, but keen-eyed still. The musket ball was lodged deep in his thigh. Seeing his father fall Lord Willoughby had rushed to his side, only to be taken prisoner with him. It was evening, pitch dark and bitter cold. Outside the dimly lit barn which served as a Parliamentarian dressing station, 4,000 men lay dead or wounded on the gentle Warwickshire hillside near the little village of Radway: ‘The field was covered with the dead,’ wrote one who survived; ‘yet no one could tell to what party they belonged.’ The cold was a blessing, some were saying: it would make the blood congeal, save them from bleeding to death. But Lord Willoughby could do nothing to stem the haemorrhage, and he doubly despaired that it should have come to this: the noble earl of Lindsey, who had begun the morning as the King’s general-in-chief, felled in the mêlée by a common musket!

There had not been a pitched battle on English soil for 130 years.

1

There had not been much of a battle anywhere for an English army in all that time. There

was

no English army. When it came to pushing the Scots back across the border, or putting down the Irish, as occasionally it did, the King would drum up a scratch force, engage officers who had gained a bit of experience with one of the continental armies, hire foreign mercenaries (Italian cavalry had fought against the Scots at Flodden in 1513) – and, when the job was done, quickly pay them off again. Standing armies were expensive. When war with France or Spain threatened, it was the navy to which the nation looked for the safeguard of the realm. Britain was the ‘sceptred isle’, and doubly blessed by her geography: only Denmark and the Kingdom of Naples had so favourably short a land border with their nearest neighbour as that between England and Scotland. Most of the inhabitants of the British Isles never saw a musket, let alone carried one.

And so in the opening moves of the Civil War, King Charles I had mustered a scratch army, derisively called Cavaliers, to do battle with Parliament’s scratch army, derisively called Roundheads, on a bright October morning in the green and pleasant English countryside between Stratford-upon-Avon and Banbury. The cores of both armies were the ‘trained bands’, the county militias under the lords lieutenant. But trained they scarcely were – certainly not

well

trained – except for some of the London bands, for the half-century since the Armada had been years of military decline. ‘Arms were the great deficiency,’ wrote one Royalist eye witness at Edgehill, ‘and the men stood up in the same garments in which they left their native fields.’ They stood, indeed – both sides – in the ancient line of battle, as the Greeks and Romans had, the Royalists at the top of the grassy slopes of Edgehill above the Vale of the Red Horse, many ‘with scythes, pitchforks, and even sickles in their hands, and literally like reapers descended to the harvest of death’. Without so much as the customary sash to show their allegiance, it was little wonder that when they fell ‘no one could tell to what party they belonged’.

The cavalry were not much better found, although the Royalist horse, whose

élan

became synonymous with the very word ‘Cavalier’, were superior to Parliament’s. They were led by Prince Rupert of the Rhine, King Charles’s nephew, dashing and ardent, who at only twenty-three had seen more recent service, in the Netherlands and Germany,

than any officer in the field that day. Of artillery – ‘with which war is made’, as Napoleon Bonaparte would famously pronounce a century and a half later – there was pathetically little: just forty-odd guns between the two sides, neither manœuvrable nor able to throw a great weight of shot. It wasn’t that the country lacked the industrial base and technological know-how: since Tudor times there had been fifty iron foundries in the Kent and Sussex Weald capable of producing cannon as good as any in Europe, and of late the output of the gunpowder mills had been increasing in both quantity and quality. It was the skill to use the means of modern, continental warfare that was lacking. In Henry VIII’s day every able-bodied nobleman had been blooded; now, not one in five had seen a battlefield. England, declared the fury in the Court’s Twelfth Night masque of 1640, the last of Charles I’s reign, was ‘overgrown with peace’.

And so 28,000 men would do battle at Edgehill, with their officers scarcely knowing what they were about. Few on either side had any illusions about their situation, however. Sir Edmund Verney, the royal standard-bearer, confided to his son in a letter the night before: ‘Our men are very raw, our victuals scarce and provisions for horses worse. I daresay there was never so raw, so unskillful and so unwilling an army brought to fight.’ He did not live to receive a reply. The same was true of the Parliamentarian army, although a certain religious zeal enlivened the ranks, like the rum ration of later wars.

Matters were made worse on the Royalist side by disputes among the senior officers. As King Charles’s serjeant-major-general,

2

Jacob Astley, began his duty of forming up the infantry, a row broke out over what that formation should be. Astley, who had seen service with both the Dutch and Swedish armies, favoured the Swedish model of three ranks.

3

But his general-in-chief, Robert Bertie, the earl of Lindsey, favoured the Dutch model in which the infantry stood five ranks deep at least – a formation that was not able to cover as much ground but which was more solid and easier to control, especially with inexperienced troops. And Lindsey wanted also to keep the cavalry in close support, for the Parliamentary commander, the earl of Essex, had fought alongside the Dutch too; and Lindsey fancied therefore that he knew how Essex would fight.

Prince Rupert disagreed. Serjeant-Major-General Astley had once been his tutor, and so he, too, favoured the Swedish model – not least in using the cavalry independently of the infantry. As the lieutenant-general Rupert was not just in command of the cavalry, he was second-in-command of the army; and since King Charles himself was at its head, he would answer only to the King. When Charles deferred to his nephew, Lindsey resigned his empty command and took his place instead at the head of the regiment he had raised in his native Lincolnshire. The earl of Forth, whose service had been with the great Swedish soldier-king Gustavus Adolphus, assumed the appointment, and the ‘Swedish’ troop dispositions were made.

There are better ways to begin a battle than with squabbling among senior officers and making infantrymen change their dispositions and then change back again. But to fight a battle without a common understanding of tactics is asking for trouble, then as now. It was what happened when armies were brought together only on the eve of battle, and when officers received their training – some of it by no means up to date – in very different schools. These things were only avoided by having a professional, standing army. Did Charles wish for such an army, now, as he faced the earl of Essex’s men? Perhaps. But what if the standing army had sided with Parliament instead? After all, Britain was an island, the Scots were manageable and the Irish, for all their intractability, did not threaten the peace of England. Best leave professional armies to the continental powers, for see how they had fuelled a war of religion across Europe for the past twenty-five years!

4

It took time to draw up 15,000 men in line, all but a couple of thousand of them on foot, especially the semi-feudal companies of countrymen with scythes, pitchforks and sickles. The trained bands, if not drilled as well as once they had been, were at least uniformly equipped with the matchlock musket and the pike – in a 3:1 ratio of pikemen to ‘the shot’. In some of the more poorly drilled county militias the proportion of pikemen was greater, for the matchlock was an unwieldy weapon, the barrel 4 feet long, so heavy, and so violent in its recoil, that it had to be fired from a rest driven into the ground. Inaccurate even over its short range, it was a crude device – in essence a steel pipe sealed at one end, with a thin bore-hole through to a ‘pan’

in which an initiating charge of powder was sprinkled and then sparked by a smouldering twist of rope (the slow match, hence ‘matchlock’) clamped in a trigger-operated lever. This fired the main charge – powder which had been poured down the barrel, with a lead or iron ball dropped in after it, all tamped tight by a ramrod. It was prone to misfire, for in rain the powder got damp and the match could go out. But with loose powder and glowing matches in close proximity, the risk of premature – and catastrophic – explosion was an even greater concern, and loading therefore proceeded at the pace of the slowest musketeer, to words of command more akin to a health and safety notice than to battlefield orders:

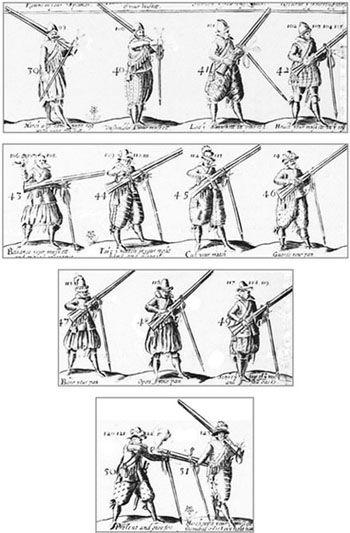

A few of the dozens of‘words of command’ needed to get the musketeers of both Royalist and Parliamentary armies to handle loose gunpowder safely and to fire volleys.

Take up your Match;

Handle your Musket;

Order your Musket;

Give Rest to your Musket;

Open your Pan;

Clear your Pan;

Prime your Pan;

Shut your Pan;

Cast off your loose Powder;

Blow off your Powder;

Cast about your Musket;

Trail your Rest;

Open your charge;

Charge with powder;

Charge with bullet;

Draw forth your Scouring Stick;

Shorten your Scouring Stick;

Ram Home;

Withdraw your Scouring Stick;

Shorten your Scouring Stick;

Return your Scouring Stick;

Recover your Musket;

Poise your Musket;

Give rest to your Musket;

Draw forth your Match;

Blow your coal;

Cock your Match;

Try your Match;

Guard and Blow;

Open your pan;

Present;

Give Fire!

With such deliberate drill the rate of fire was glacial, even with alternate ranks firing and reloading. It was fatal, not just ineffective, to discharge at too great a range, for if the fire fell short the enemy’s musketeers and pikemen would be able to close with them before another volley (fire by the entire line) could be got off. And if it were cavalry advancing against the line there was scarcely time to get off a volley at all before the pikemen needed to take post in front. At Edgehill the pike they carried was 16 feet long, making the line even more unwieldy to manœuvre, for the pikemen had to wedge the butts in the ground and brace themselves to make a solid wall of steel against cavalry or the enemy’s pikes. Little wonder, then, that even in the best-trained bands there were three of them to every musket.

At Rupert’s urging, King Charles placed his cavalry – the ‘horse’ proper as well as the dragoons (who fought dismounted with sword and musket rather than from the saddle)

5

– on either end of the line to prevent his flanks from being turned, and to allow freedom of movement when the moment came to charge. And Rupert, in command of the stronger right wing of the cavalry, would be looking for just that opportunity, for in many a battle on the Continent he had seen the enemy’s line scattered by a well-timed charge.