The Life of Lee (16 page)

Authors: Lee Evans

‘I can do the Frisbee Flop,’ I said, blurting out the first thing that came into my head.

They looked confused. It was a nervous reaction from

me. I’ve used it before and it always gets the desired effect. Not the Frisbee Flop line, no – but I’ve randomly shouted all sorts of things in a futile attempt to avert various different crises. Saying ‘Plums!’ is a good one, or just point – it doesn’t matter at what, it simple distracts people.

But at this moment it was the Frisbee Flop.

Mind you, I wasn’t lying because I had, back in my bedroom in Bristol before I got to Billericay, been an avid watcher of the Olympics. In particular, I had been fascinated by the Frisbee Flop. I called it that but it is, of course, actually named the Fosbury Flop. It was a brand-new jump that had been invented by the American athlete Dick Fosbury at the Mexico City Olympic Games in 1968.

From an early age, I had been enthralled by a jump that – when the bar is removed from the equation – just makes you look like a nutter lunging sideways and landing on your back. In Bristol, I’d spent hours practising it by standing at the foot of my bed then suddenly hurling myself sideways. I’d keep my arms pinned to my sides, pulling a sort of startled face as I landed successfully on my back on the bed, the mattress cushioning my fall like one of those crash mats they have on the telly. Then I’d spring back up on to my feet and run around the small space, waving my arms and making an ecstatic crowd noise. I was good at that, having spent so long alone. I’d learned enough noises to put the BBC Sound Effects Department out of business.

But here’s the cruncher: you definitely need a mattress to break your landing or it doesn’t work. The hard ground doesn’t cushion your fall nearly as effectively. This is what

I tried to explain to those two lads at school in Billericay, but Helmet Head immediately began boasting that he could do the Frisbee Flop too.

I didn’t care – it wasn’t a challenge or anything. I even tried to stop him. I stepped forward and said, ‘’Ere, biss don’t want to try that’un, my cocker,’ in my Bristolian accent, but he pushed me back. His weasel friend stopped giggling for a moment and came right up close, touching his forehead against mine in a sort of slow-motion head butt. Then, while still staring at me all hard like, he pulled away and began giggling again.

I tried talking Helmet Boy out of it, but it was too late. He adopted a very serious demeanour as he took a short run-up. With the concentration etched on his face, he shouted out a guide to what he was doing.

‘What … I … do … is … jump … then … curl … over … and …’ SNAP!

You could hear the snap all the way across the county, because everybody on the playing field just stopped what they were doing and stared at us. I was standing next to Weasel, who’d stopped giggling and was looking ashen and stony-faced at Chubs writhing on the floor in front of us. After not pulling his flop off properly, he’d landed with his full weight on his arm, snapping it in two like a dry twig. ‘Biss, eer, your arm’s pointen in enover doirection, my cock.’ As if he didn’t know!

It was weird because he wasn’t crying, well, not yet anyway. He just lay there, his face contorted, his mouth wide open, doing a kind of primal scream, like the telly with the volume turned down – presumably because he was in so much pain. I asked him, ‘Should I gow and get

a teacherrrr or summut?’ But he didn’t answer, he just finally flipped, inhaled and started screaming. I panicked and ran.

Weasel Boy and I watched as Helmet Head was taken away on a stretcher into an ambulance. I never saw him again, because soon afterwards I moved on to senior school. I wonder what happened to him. He probably became an Olympic high jumper.

Still, I’d made an impression. And, after that, nobody at the school ever messed with me again. They thought that ‘Farmer Giles’ possessed strange West Country powers to inflict damage on Essex lads without even trying!

But it didn’t help me fit in. I’m afraid I still felt like the Odd Boy Out.

15. Raging Bull

The very physical sport of boxing was always described by Dad – from the well-upholstered comfort of his armchair – as ‘a proper, working-class sport’. He believed that passionately – remember his initial desire to name me ‘Cassius Clay Evans’? To punch home his point, he could sometimes get quite angry and animated in his defence of the sport. He would rise up and dance around the lounge, mock-boxing as if in the final round of a world title fight, hands up by his chin, head bobbing around like a demented chicken on ‘wacky baccy’. He would throw the odd jab towards Wayne and me, who stood rooted to the spot in stunned fascination at his pugilistic demonstrations.

‘Careful, Dave, you’re going to knock something over,’ Mum would carp, not even lifting her eyes from another one of her production-line jumpers, smiling to herself as she stared down at her rat-a-tat-tatting needles. It wasn’t very often that we were all together as a family, and Mum always glowed when we were. She liked the noise and the banter that went on whenever Dad was home after months away.

What there was to knock over, God only knows. Dad could have set about our home like a man possessed with a large sledge-hammer and only succeeded in doing about

two quid’s worth of damage. We hardly had anything, so what he might bump into was anybody’s guess.

‘Boxing is a sport …’ Dad would begin, stopping for a lug of his fag before moving around the room and beginning to gear up to his usual Churchillian ‘I know what I’m talking about’ speech. All blokes do it, in the safety of their own home, in front of the wife and kids. There they are Einstein, the great intellect that demands to be listened to. And, it goes without saying, if only the world leaders would consult them, they might learn a thing or two. If we could have afforded a phone back then, the world leaders would have been constantly trying to get through, but they would’ve had to join the queue to speak to the top adviser. Of course, as soon as all these blokes get out of the house and into the real world, competing with everyone else, they find they actually have a brain the size of an amoeba and would dump in their Y-fronts if confronted by so much as a local MP.

‘A sport,’ Dad would rattle on, his lecture now in full flow, ‘that can, through sheer hard work, raise a man up from the absolute depths to the very pinnacle of our society. It is a sport that does not discriminate. It is attended by lords, dukes and even royalty, as well as the ordinary working man in the street.’

Dad boxed during his service in the army, and he thought it would be a good idea to drill it into Wayne and me. So every Christmas or birthday, there would be the obligatory pair of boxing gloves, inflatable punchbag, or – the one I liked because it didn’t hurt so much – a boxer on a stick. Under the boxer’s robe were two levers you pushed to make the plastic boxer throw a punch.

Me and Wayne wearing our obligatory boxing gloves that we got every Christmas.

I hated boxing when I was a kid because it felt as if I always came off worst in the pecking order. As soon as the gloves were unwrapped at Christmas, I knew at some point that day I would have to reluctantly slip them on. The constant goading from Dad and Wayne would chip away at my pride and, not wanting to look weak in any way in front of Dad, I had to put up or shut up. It was a constant competition in our house, as Wayne and I tried to gain some form of approval from Dad.

I don’t know if Dad encouraged it between us – in particular, the contest to see who was the toughest fighter. My efforts on the boxing front were always futile. Dad would look on as Wayne bashed the crap out of me. My brother had this incredible move that would catch me unawares every time. Mid-fight, as I staggered around the middle of our lounge, visibly exhausted, Wayne seized his chance. He would suddenly dart forward and with his leading foot step on my front foot, so I was trapped, pinned to the floor like a rat in a trap, unable to back off or go anywhere. Then he would bend forward and follow through with a massive head-numbing, over-arm punch that came out of the sky like a meteorite, thumping down on to the top of my head and leaving me seeing more stars than Patrick Moore on a clear night.

It was that same devastating punch Wayne would later use to massive effect to win fights at amateur boxing club level. After moving to Billericay, we both joined Berry Boys, a local amateur boxing club. By then things were definitely a little different for me. I’d learned to be a bit tougher; I was no longer willing to take a sucker punch from my big brother. Instead, I’d mastered the artful

technique of dodging. I was brilliant at it. I could bob, weave and dance around the ring in my over-sized shorts in a way Fred Astaire would have been proud of, my skinny white legs bopping across the canvas.

Maybe I was now more determined because I was slightly older, or perhaps it was because I thrived under the rules and regulations of club boxing, under proper supervision, or maybe I just lapped up the camaraderie and fun of being with all the other boys at the club.

The sparring still hurt, but I had learned to defend myself a little better. I began to enjoy it – and my love of boxing was to continue into later life.

Celebrating with Heather after winning my first fight in the East End of London at one of the many boxing shows.

I especially loved the discipline of the intense training sessions. I also relished the fact that all the fighters at the club had something to train for, namely, the boxing shows. These were organized by the Amateur Boxing Association and pitted fighters from different clubs across the county against each other. It was usually an evening event and always well attended, mostly by the families of the young boxers, who came to shout their support.

There was always a tense, edgy atmosphere to these occasions. This was made all the more important for the young boys fighting by the presence of some of the regular faces and characters well-known to the boxing fraternity, who had either been in the fight game for years themselves, or were retired trainers, all unable to keep away from the buzz of the ring. They were looked up to by all the young boxers.

Every competition was different. Sometimes it was a relaxed, casual affair, a few bouts held, say, at a local working man’s club in the East End of London, where a ring was simply erected in the middle of the room. By the

time the first bout punched off, the air in the club would be hot and heavy, laden with thick cigarette smoke that made breathing difficult. How the boxers managed the highly physical bouts with such short supplies of oxygen was beyond me.

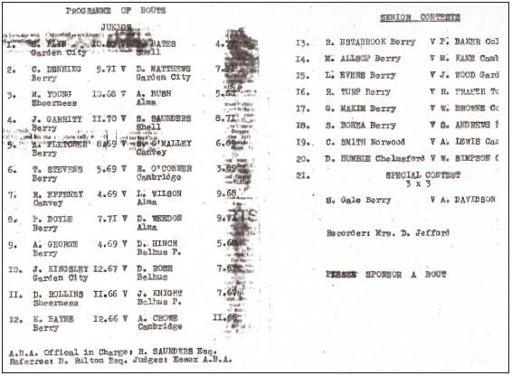

Berry Boys boxing programme – Fight No. 15 – they spelt my name wrong!

The rowdy tables were full of mostly lively, rotund, sweating riff-raff, some getting so excited they would be leaping out of their seats. Somehow, in their heads, they themselves were in the ring, as they demonstrated by incessantly bobbing around, wiping and flicking their nose with the end of their thumb and air-boxing. All the while, they were shouting their genius instructions to the poor young lads who were actually doing it for real, battering hell out of each other in the floodlit ring.

Then there were the shows I preferred, held at a posh hotel somewhere Up West, where the crowd all dressed up smartly in dinner suits and dicky bows. It was still the same riff-raff, but it somehow felt more professional and glamorous. Instead of the air being thick with cigarette smoke, this time it was cigar smoke.