The Life of Lee (13 page)

Authors: Lee Evans

‘Thanks, Dave. How are the crowd?’ asked Tommy.

Dad told the truth. ‘They’re great, but I think they’re getting a bit pissed off.’

Tommy understood. ‘Oh; all right, thanks. I’ll keep me eyes open then.’ He stopped in the doorway and looked down at me. ‘Who’s this?’

‘That’s my boy. Come on, son, out you come.’ I walked forward, staring at what was to me a giant. That moment has remained etched in my memory ever since. This was a man who embodied showbiz: even chatting away offstage, he oozed charisma from every pore. Wow, I thought, I’d love to be like that!

Tommy Cooper – yes, Tommy Cooper! – bent down and shook my hand. ‘Hello, son. What’s your name?’

I couldn’t answer – I was too nervous. So Dad answered for me. ‘Lee.’ Then Dad ushered me out.

‘Lee? That’s a nice …’

Just then the manager rushed back into the hall. ‘Ten minutes, Tommy.’

‘I need a radio mike,’ shouted Tommy.

Then the other door opened, and Tommy’s son burst in, pushing huge travel cases on wheels. Tommy sped into action. ‘Right, son, you know what to do.’ With that, Tommy pulled a stick from one of the boxes and gave it to his son. The manager hurried back in and gave Tommy a radio mike.

As Dad gathered his stuff together, I watched Tommy through the door begin to get ready. He took his shirt off and put on a stage shirt and over his head he placed a microphone holder. He shoved the mike into it and began speaking. ‘One, two. One, two …’ I could hear the crowd going wild.

Tommy carried on getting ready and speaking into the mike. As he did this, I could see his son on stage prodding the back of the curtain with the stick while at the same time setting up a table.

‘What’s this? Where am I?’ Tommy went on, as his son poked the curtain some more. It was fantastic. I could hear the audience laughing their heads off.

By now, Tommy Cooper had his trousers on and had set up some props. I watched, rooted to the spot. He carried on with the same routine for at least ten minutes. What amazed me was that he hadn’t even walked on stage, and yet the audience were roaring with laughter at the mere sound of his voice. You could feel it backstage, right in the pit of your stomach. That was some talent.

Slightly flustered, he came out of the dressing room and walked to the side of the stage, all the time nervously checking his pockets. Suddenly, I heard the manager start

to introduce him. As Tommy Cooper stood in a gap between the curtains, beams of spotlight trickled through, silhouetting his huge stature. The audience cheered even more loudly.

‘Ladies and gentleman, Tommy Cooper!’

He whipped open the curtain and walked out into the bright lights. As the curtain flopped shut, all I could hear – even through the curtain that tends to muffle everything on stage – was a cacophony of clapping and laughter. It was the definition of a ‘wall of sound’. Through a tiny gap in the curtain, I could just pick out a woman in the front row saying, ‘Blimey, ain’t his feet big?’ It’s safe to say that he stormed it.

That was a turning point for me. I spent the car journey home in complete silence. All I could think about was how funny Tommy Cooper was, but without seemingly trying. He was just funny. I played it over and over in my mind: Tommy Cooper walking through those curtains, and the roar of the crowd, the laughter. It was not polite or restrained, but uninhibited, bellyaching laughter. That’s what I liked – when it actually hurt to laugh.

They were laughing because he was funny; in fact, they were even cracking up ten minutes before he came on stage. The mere prospect of his appearance was making them laugh – what sort of power was that? When he did appear, they were not cracking up at his lines because he hadn’t said anything yet, but somehow they sensed his funniness. His mere demeanour was enough to set them off. They knew he simply had funny bones. I thought, ‘How incredible that must feel, to have the audience eating out of your hand before you even walk on stage, to be

so funny they’re already your friends before they’ve even clapped eyes on you!’

I know now that comes from years and years of hard graft in the clubs and theatres up and down the country. I know now that Tommy Cooper probably felt really insecure about whether his show would catch fire that night I saw him. A comedian never forgets it if something doesn’t work. Even when that crowd laughed at everything he did that night, he was probably wondering all the time if it was good enough, hoping right until he said goodnight that it would be OK. That anxiety is just part of a comedian’s DNA. But what I saw of Tommy Cooper when I was just a kid touched me deeply. It was truly awe-inspiring. It planted a seed in my head which, over the coming years, was to grow and grow.

It’s difficult to put into words what I felt that night. But it’s that sense which has driven me throughout my life. It’s the sensation you get from a performer who makes you feel all tingly inside, as if he has touched you in some way – whether it be through pathos or familiarity. You feel safe with him in front of you, and when he says goodbye, he leaves you with that infectious sense of something hopeful and wonderful.

There are precious few performers who can do this, who can speak to you personally, connect with something deep inside you and tickle your soul. I know that it’s each to their own and that one person’s illumination is another person’s ignorance, but that’s what drives me.

From time to time, people have accused me of walking about in a dream world, seeing things around me that

others don’t see. But, you know what, I don’t care. I’ve never liked beige.

Tommy Cooper, Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Billy Connolly, Eric Sykes, Morecambe and Wise and Freddie Starr – they are just a few of the performers who have funny bones. They can make you laugh without saying a single word.

Bob Hope, Bob Monkhouse – anyone called Bob, really – they’re the kings of the one-liners. They’re brilliant in their own right, but they don’t get to me in the same way as the Funny Bones Brigade. I always preferred Harpo to Groucho Marx. The natural comics exhibit an Everyman feeling and a sense of pathos that genuinely touches me.

I would rather be in that world than anywhere else.

12. The Beginning of My Life in the Theatre

No one ever went abroad for their holidays in those days. It was unheard of, reserved for the super-rich. For the majority of people, if you could get some money together, you might take your family to one of the many seaside towns and enjoy the summer shows, which provided a rare glimpse of glamour.

A big part of our childhood was spent travelling around the country for summer seasons with Dad. The shows back then were huge productions that would be considered unaffordable now. A typical summer theatre show company might consist of at least forty people, sometimes more. Once everyone had got to know each other, it became one big family, with all the ups and downs, trials and tribulations that entails. But as Mum always said, ‘What goes on backstage, stays backstage.’ Maybe the Las Vegas Tourist Board stole that phrase.

Eastbourne, 1984, during the summer season, watching my dad rehearsing the trumpet. I would sit for hours and listen while he practised.

Once everyone got to know that Wayne and I were Dave’s kids, we could hang around anywhere in the theatre and no one would move us on. Mostly they just ignored us and got on with their jobs. They were accustomed to all of us kids being around. The offspring of all the different acts would always get together to form a large gang.

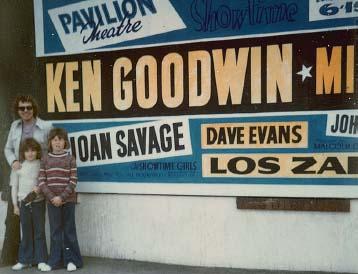

Great Yarmouth – Dad’s summer season with Ken Goodwin and the great Mike Reid.

We quickly found out that show people are more tolerant of the quirky kind of behaviour that ‘normal’ society might see as strange. They appear to have an ‘us and them’ attitude; they believe they conduct themselves in a way that the audience wouldn’t necessarily understand. Everyone I have ever known in show business – whether a member of the technical crew or a performer – takes it for granted that the show is the most important thing of all. A lack of inhibition comes with the territory. If a performer walked about with a banana up his backside, no one would bat an eyelid, as long as the show went on without a hitch.

No one took any notice of other company members, say, having affairs, walking around with no clothes on, swearing, drinking, fighting, rowing. It was like you belonged to a small, private community. All sorts of odd antics were allowed within those walls.

I always found that funny. In any other job, certain behaviour would just not be tolerated. If you worked in a bank, for example, you would be fired on the spot if you suddenly got naked to change into your work clothes before serving at the counter. You would also be dismissed instantly if you were a labourer and you refused to work with someone who mixed up the cement carelessly and was making you look bad. Can you imagine a road digger throwing his drill down, storming across the dual carriageway and shouting: ‘I refuse to work with inferior tools! If you need me, I’ll be in the tea hut!’?

By the time I was thirteen, I’d already seen stuff that most people might feel I shouldn’t have: nudity, drinking, swearing. And that was just me. Only kidding, I never swore – but I did drink in the nude.

Everyone loved the dancers – they would always spoil kids. I’d often find myself in the dancers’ changing rooms during breaks or when a comic was on. I never intended to be in there, but they would always ask me in. If they saw me hanging about, I’d hear: ‘Lee, Lee, come in ’ere and keep us company.’

I loved the dancers. They had a way about them. Maybe it’s their training, but they always moved so elegantly, and their bodies were so lithe and beautiful. It never bothered them that I was there – they liked nothing better than to relax by walking around with hardly any clothes on. Funny, it never bothered me either.

The only weird bit was the dancers’ make-up. From the stalls in a theatre, they look gorgeous and glamorous but, curiously, close up it looks as though they’ve had a fight at the cosmetics counter. The make-up looks like it’s been applied by an uncontrollable weightlifter who’s been sacked from his previous job stamping passports because of his nervous muscle spasms. But, on stage, the dancers have the appearance of angels.

I just adored hanging around backstage when they were performing. I would find a place to sit out of the way somewhere in the wings and just marvel as they kicked, jumped and danced, a smile permanently fixed on their heavily made-up faces.

When there was a big routine involving all the dancers, I would watch them gather excitedly at the side of the stage. There they would be, nattering about boyfriends, where they might be going after the show, or complaining about having to do a laundry run tomorrow. But as soon as the curtain went up, they would all be in their places,

with bright smiles lighting up their faces and their over-the-top eyeshadow sparkling in the spotlights.

It was like a giant clock, where at certain points every cog would just click into place. It was run with military precision and punctuality, as they had to bring down the curtain at an exact time in order to be ready for the second show.

Dad on stage playing one of the many instruments at which he excels. A mean sax player – as a boy, I loved to watch him on stage.