The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language (33 page)

Read The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

VP

VNP(PP)

“A verb phrase can consist of a verb, a noun phrase, and an optional prepositional phrase.”

PP

P NP

“A prepositional phrase can consist of a preposition and a noun phrase.”

N

boy, girl, dog, cat, ice cream, candy, hotdogs

“The nouns in the mental dictionary include

boy, girl,…

”

V

eats, likes, bites

“The verbs in the mental dictionary include

eats, likes, bites

.”

P

with, in, near

“The prepositions include

with, in, near

.”

det

a, the, one

“The determiners include

a, the, one

.”

Take the sentence

The dog likes ice cream

. The first word arriving at the mental parser is

the

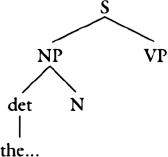

. The parser looks it up in the mental dictionary, which is equivalent to finding it on the right-hand side of a rule and discovering its category on the left-hand side. It is a determiner (det). This allows the parser to grow the first twig of the tree for the sentence. (Admittedly, a tree that grows upside down from its leaves to its root is botanically improbable.)

Determiners, like all words, have to be part of some larger phrase. The parser can figure out which phrase by checking to see which rule has “det” on its right-hand side. That rule is the one defining a noun phrase, NP. More tree can be grown:

This dangling structure must be held in a kind of memory. The parser keeps in mind that the word at hand,

the

, is part of a noun phrase, which soon must be completed by finding words that fill its other slots—in this case, at least a noun.

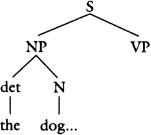

In the meantime, the tree continues to grow, for NP’s cannot float around unattached. Having checked the right-hand sides of the rules for an NP symbol, the parser has several options. The freshly built NP could be part of a sentence, part of a verb phrase, or part of a prepositional phrase. The choice can be resolved from the root down: all words and phrases must eventually be plugged into a sentence (s), and a sentence must begin with an NP, so the sentence rule is the logical one to use to grow more of the tree:

Note that the parser is now keeping

two

incomplete branches in memory: the noun phrase, which needs an N to complete it, and the sentence, which needs a VP.

The dangling N twig is equivalent to a prediction that the next word should be a noun. When the next word,

dog

, comes in, a check against the rules confirms the prediction:

dog

is part of the N rule. This allows

dog

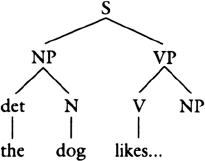

to be integrated into the tree, completing the noun phrase:

The parser no longer has to remember that there is an NP to be completed; all it has to keep in mind is the incomplete S.

At this point some of the meaning of the sentence can be inferred. Remember that the noun inside a noun phrase is a head (what the phrase is about) and that other phrases inside the noun phrase can modify the head. By looking up the definitions of

dog

and

the

in their dictionary entries, the parser can note that the phrase is referring to a previously mentioned dog.

The next word is

likes

, which is found to be a verb, V. A verb has nowhere to come from but a verb phrase, VP, which, fortunately, has already been predicted, so they can just be joined up. The verb phrase contains more than a V; it also has a noun phrase (its object). The parser therefore predicts that an NP is what should come next: