The Knight in History (29 page)

Read The Knight in History Online

Authors: Frances Gies

In 1424 Bedford prepared to finish the conquest of Maine, assembling troops at Rouen. Marching south in August, the English met the French army in an open field outside the town of Verneuil, on the Norman border northwest of Chartres. William Worcester tells us that Fastolf “was created a knight banneret at the battle of Verneuil by John, regent of the kingdom of France” whether before or after the battle is not specified. At this “second Agincourt,” according to Worcester, Fastolf “won by fortune of war about 20,000 marks.”

18

Fastolf’s great coup, executed with another captain, Lord Willoughby, was the capture of the young duke of Alençon, who lived to be a favorite companion-in-arms of Joan of Arc. Since he was of royal blood, Alençon had to be turned over to Regent Bedford, but Fastolf and Willoughby were promised in return a “reasonable reward” of 5,000 marks apiece. Each actually received a thousand marks. Alençon raised the ransom in three years but Bedford apparently kept the money; twenty-five years later Fastolf sued Bedford’s estate and suggested that Willoughby’s widow do likewise.

19

Despite his collection problems, Fastolf did well out of the war. In November 1424 he signed an indenture with Bedford to serve as captain of “eighty mounted men-at-arms [including himself] and two hundred and forty archers, for one whole year,” beginning at Michaelmas past (September 29), the troops to be employed in the conquest of the county of Maine and its border region “and anywhere else in the kingdom of France where it shall be the will of the said lord regent to ordain.”

The wages were specified: “For a knight banneret, captain of men-at-arms, four shillings sterling a day in English money; for a knight bachelor, likewise a captain, two shillings sterling; for a mounted man-at-arms, twelve pence sterling a day, with the accustomed rewards; and for each archer, six pence a day of the said currency…. And these wages shall be paid as from the day of the first musters,” after that in advance for two six-week periods, then in advance by quarter-years. “And the said lord regent shall have both a third part of the profits of war of the said grand master [Fastolf], and a third of the thirds which the men of his retinue shall be obliged to give him from their profits of war, whether prisoners, booty, or anything else taken…. And the said grand master shall have any prisoners who may be taken during the said period by him or by those in his retinue: with the exception of any kings or princes, whoever they may be, or sons of kings…or other captains and persons of the blood royal…each and all of whom belong to the said lord regent, and he shall pay a reasonable reward to him or those whose prisoners they shall be….” Fastolf undertook in return to serve the king and the regent and to use his company “in the best manner and means known to him, or which the said lord regent shall command him.”

20

The success of the subsequent campaign owed much to Fastolf, and Fastolf’s fortunes owed much to the campaign. In August 1425 Le Mans capitulated to him and he was made lieutenant of the town under the earl of Suffolk; in September he captured the castle of Sillé-le-Guillaume, west of Le Mans, and was named its baron. The following year he won a rare new honor, being installed Knight of the Garter.

The Order of the Garter, conceived by Edward III in 1344 in imitation of King Arthur’s Round Table, was the first of many honorary “secular orders” of knighthood, some short-lived, some lasting for centuries, designed to reward valor and glorify knighthood and to create a bond between the patron of the order and those on whom he bestowed membership: the Order of the Star founded by King John II of France, the Porcupine of the duke of Orleans, the Ermine of John IV of Brittany, the Dragon of René of Anjou, the Golden Shield of Duke Louis of Bourbon, the Golden Fleece of the dukes of Burgundy. Membership in the Order of the Garter was limited to the king and twenty-five knights. Of the original members all but one had been captains in France (one was Du Guesclin’s old adversary Henry, duke of Lancaster, another Sir John Chandos), all but two were English (one of the two was the Gascon Captal de Buch, another of Du Guesclin’s foes).

21

Fastolf continued to amass profits, which he forwarded through English intermediaries in Normandy or through Italian merchants in Paris to two agents in England, John Wells, an alderman and grocer of London originally from Norwich and evidently a relation of Fastolf’s, and John Kirtling, his chaplain, who handled both the revenues from Fastolf’s English manors and the proceeds of war. The two acted as Fastolf’s bankers and brokers, and when Fastolf’s money remained in their hands for a length of time, they paid him five percent yearly interest; other tradesmen of Paris, London, and Great Yarmouth were also trusted with his funds. Such investments were temporary. Like most of his fellow captains, Fastolf put his money permanently in land, furniture, jewels, and plate.

22

After a stay in England to deal with domestic politics, Bedford returned to France in March 1427, bringing with him Sir John Talbot, a talented soldier, to serve as chief field commander in a fresh offensive designed to win the war by breaking the French defense line on the Loire and conquering central France.

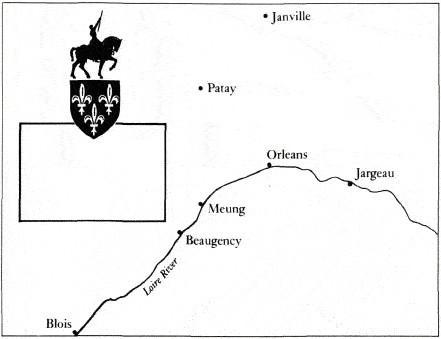

In the critical campaign that followed, Fastolf earned his greatest military distinction but, immediately after, a lasting and probably undeserved opprobrium. In October 1428, the English began the fateful siege of Orleans, with an Anglo-Burgundian army under the command of Talbot and Sir Thomas Scales. On February 12, 1429, Fastolf led a large commissary train from Paris bringing “herring and Lenten stuff” to the besieging army. Near Janville, a fortified town twenty miles north of Orleans, Fastolf learned that a large French and Scottish force was on its way to intercept him. Halting at once, he deployed his wagons in a circle. The French and Scots arrived and set up small cannon, which bombarded the wagons with some effect; but when the French and Scottish knights insisted on attacking, they were driven off by the well-protected English archers. Fastolf ordered his men to mount and counterattack, and the “Battle of the Herrings” turned into a rout with heavy casualties. Dunois, the “Bastard of Orleans” and leading French captain, was wounded, and Sir John Stewart, constable of Scotland, killed.

A chronicle called the

Journal du siège d’Orléans

reported that Joan of Arc, in Vaucouleurs attempting to persuade Robert de Baudricourt to send her to the king, had a clairvoyant revelation of the French defeat and used it to convince Baudricourt of her powers. True or not, after Joan had arrived in Orleans, Fastolf was much in her thoughts. When Dunois told her that Fastolf was again approaching with reinforcements, she exclaimed, “Bastard, Bastard, in the name of God, I order you that as soon as you hear of the arrival of Fastolf you will let me know, for if he gets through without my knowing it, I promise that I’ll have your head cut off.”

23

Shortly after, the French assault was delivered that ended the siege. As the English retreated, the French prepared to attack Jargeau, east of Orleans. Again a report signaled the approach of a relief army commanded by Fastolf. The French captains hesitated but Joan declared that they should not fear any numbers, for God was conducting the campaign.

24

At the moment, Fastolf was actually still in Paris. Chronicler Jean Wavrin, a Burgundian enrolled in Fastolf’s service, gave an eyewitness account of his master’s part in the ensuing campaign. Receiving news of the French threat to Jargeau from Talbot, Bedford ordered Fastolf south with “the company of…about 5,000 combatants.…In this brigade were Sir Thomas Rempston, an Englishman, and many other knights and squires native to the kingdom of England.” The army halted three days in Etampes, then marched on to Janville, where they waited for reinforcements that Bedford had summoned from England and Normandy.

Fastolf was still in Janville when word came that Jargeau had fallen, Meung was threatened, and the French were besieging Beaugency. “This news gave them great distress, but they could do nothing at the moment,” Wavrin wrote. “They met in council to determine what they should do.” At that moment Talbot arrived, with a small force, not the expected reinforcements, but “about forty lances [a lance was a knight and three or four auxiliaries] and two hundred archers, and their arrival was very joyous for the English…for he was at that time regarded as the wisest and most valiant knight of the kingdom of England.”

THE LOIRE CAMPAIGN

Fastolf, Thomas Rempston, and the other English knights dined in Talbot’s lodgings. After dinner, the trestle tables cleared and removed, they resumed their council. Fastolf argued caution; English losses at Orleans and Jargeau had been heavy, their forces were weakened and exhausted; therefore he advised them to abandon Beaugency and “take the best treaty [truce] they could obtain” from the French, returning to their “castles and strong places” to recoup their strength. The advice was not welcome to the other captains, “especially Lord Talbot, who said that even if he only had his own people and those who wished to follow him, he would fight with the aid of God and

monseigneur

St. George.” Fastolf, realizing that he was wasting his breath, left the council, “and the captains and chiefs of squadrons were ordered to be in the field the next morning.”

When the army assembled, with standards, pennants, and banners flying, Fastolf again warned of the “dangerous perils that they might incur…and that they would only be a handful of men in comparison with the French, assuring them that if fortune turned against them, everything that the late King Henry had conquered in France, with great effort and over long time, would be on its way to perdition, wherefore he urged them to wait a little until their strength was reinforced.”

When his advice was again ignored by Talbot and the other captains, Fastolf resigned himself and ordered his men to march toward Meung. The English, Wavrin writes, “rode in very fine order,” but when they reached a point a league from Meung, the French, warned of their arrival, rode out with “about 6,000 combatants, led by Joan the Maid, the duke of Alençon, the Bastard of Orleans, the Marshal de La Fayette, Poton [de Xaintrailles], and other captains,” ranging themselves for battle on a little ridge, for a better view of the English position. The English gave commands, “following the practice of King Henry [V] of England,” to dismount and for the archers to drive pointed stakes into the ground, protecting their position. Two heralds were then sent to the French, suggesting that the issue be settled by combat between three knights from each side. To this chivalric suggestion the “people of the Maid” replied only: “Go and find lodgings, for it is late; but tomorrow, please God and Our Lady, we will see you from closer at hand.”

The English continued on to Meung, where the town remained in English hands but where the French had captured the bridge over the Loire. There the English army spent the night, bombarding the bridge with their artillery in the hope of crossing the river to the southern bank and relieving Beaugency from that side.

In the morning they rose and heard Mass and were preparing to assault the bridge when a messenger arrived with word that Beaugency had surrendered and that the French were approaching. The assault was canceled, and the army assembled in the fields outside the city, where it formed in line of march to retreat to Paris: the vanguard, then the artillery and supply train, then the main contingent, led by Fastolf, Talbot, and the other captains, then the rearguard. “About a league” from the town of Patay the army halted, warned by the rearguard that they were being pursued. Scouts were sent out, and the army was ordered to deploy for battle, but the French attacked before the archers could plant their defensive stakes. Fastolf spurred toward the vanguard, intending to rally it to the main body, but its captain mistook his action for a signal for flight and galloped from the field, followed by his men. Realizing that the battle was already lost, Fastolf declared that “he would rather be dead or captured than to flee shamefully and abandon his men.” But Talbot was taken prisoner, his men slaughtered, and “Sir John Fastolf left, with a very small company, uttering the greatest lament that I have ever heard a man make,” recorded Wavrin.

25

Another Burgundian chronicler, Enguerrand de Monstrelet, not an eyewitness, wrote an account of the battle that contained a hostile picture of “messire Jehan Fastocq” fleeing the battle “without striking a blow,” and for his cowardice being stripped of the Order of the Garter by Bedford.

26

No source confirms the incident, and a historian of the Order believes that such an action would not have been within Bedford’s power.

27

Talbot is known to have severely criticized Fastolf’s behavior, and a decade later brought charges against him before the king and his council.

28

The charges were dismissed, but Monstrelet’s account, which in making Fastolf a scapegoat probably reflected much current opinion, was adopted by English historians of the sixteenth century. These writers were in turn the sources for Shakespeare’s

Henry VI, Part 1

, in which Fastolf’s cowardice is blamed for the English defeat. In the folio edition, Fastolf’s name is spelled “Falstaff,” in later editions corrected to “Fastolfe.” When Shakespeare later wrote

Henry IV

, he at first named the disreputable and cowardly old knight, friend of young Henry V’s carousing days, after Sir John Oldcastle, a member of the pre-Protestant Lollard sect who was executed as a heretic in 1417. Oldcastle’s descendants persuaded Shakespeare to change the name, and as a substitute he reverted to “Falstaff,” the corrupted version of “Fastolf.”

29

The character was so successful that he was given a final bravura appearance in

The Merry Wives of Windsor

. History has left no clues as to Fastolf’s physical appearance, but his intelligence and ability are beyond question and there is little doubt of his courage. Shakespeare, however, fixed for posterity the image of “Falstaff” as a corpulent and cowardly buffoon.