The Knight in History (24 page)

Read The Knight in History Online

Authors: Frances Gies

FOURTEENTH-CENTURY BRASS RUBBING OF THE TOMB OF SIR HUGH HASTINGS SHOWS REINFORCING PLATES ON MAIL.

(BRITISH LIBRARY, ADDIT. MS. 32490 B. 12)

In whatever form, armor was virtually indestructible (damage could be repaired by the blacksmith) and was handed down from grandfathers and fathers to sons and grandsons. The work of certain armorers and their centers—Milan, Nuremberg, Toledo—was especially esteemed, and later Du Guesclin took the opportunity of his stay in Spain to equip himself with Spanish mail.

While Du Guesclin was graduating from childish to adult tournaments, the quarrel between Edward III of England and Philip of Valois over the crown of France was slowly ripening into war. As maternal grandson of Philip IV, Edward had a stronger claim than his Valois rival, but Philip’s lawyers exhumed the ancient Salic law and argued that royal descent had to be through the male line.

10

Edward was only sixteen at the time the question arose (1328) and lost out, but several years later a minor incident aggravated a problem more deep-seated than succession. The great principality of Aquitaine, comprising most of southwest France, inherited by marriage by the English crown, awkwardly owed feudal homage to the kings of France. Both the act of homage and Aquitaine’s indeterminate borders created trouble. Edward, now a grown man, combined his immediate with his long-term grievances and put forward his claim to the French throne.

At nearly the same time (1341) a second, very similar successional quarrel broke out in Brittany, a quasi-independent province (like Aquitaine) whose duke left a niece and a half-brother as potential heirs. The half-brother, Jean de Montfort, claimed the crown on the basis of the Salic law, never heretofore applied in Brittany (or any other province). The niece, Jeanne de Penthièvre, was the lady whose marriage to Charles de Blois was celebrated in the tournament at Rennes where Bertrand du Guesclin and his father had met. She appealed to Philip of Valois, now Philip VI of France, uncle of her husband. Jean de Montfort on his side appealed to Edward III of England. As a result, the English and French monarchs were doubly arrayed against each other over the question of female succession, but ironically enough, on opposite sides in the two cases, Edward upholding female succession in France and rejecting it in Brittany while Philip defended it in Brittany without admitting it in France.

No one guessed that the Breton dynastic war would rage and smolder through twenty-three years, much less that the larger conflict would come to be known as the Hundred Years War and have, among other results, a large impact on the institution of knighthood. An augury came in the first great battle of the war, at Crécy in 1346, in which Philip’s old-fashioned army, whose principal element was the armored horseman, was routed by Edward III’s slightly smaller but more modern force, which included a strong contingent of archers armed with the Welsh longbow. At one time much was made of the effectiveness of the longbow, but except for its more rapid rate of fire it had no advantage over the crossbow, which it never replaced in continental Europe. The English success with the longbow had its chief effect on military practice and consequently on knighthood by stimulating interest in the crossbow, a compact, easily fired weapon that owed its muzzle velocity and consequent range and accuracy to its use of horn, later metal, instead of wood as the power source.

BATTLE OF CRÉCY, 1346, FROM THE

CHRONIQUES

OF FROISSART.

(MUSÉE DE L’ARSENAL, MS. 5187, F. 135V)

More significant both for the future of warfare and the future of knighthood was the radically new organizational basis of Edward’s army. Philip had assembled the ancient feudal host by the traditional summons to the royal vassals, who in turn called on their knights and retainers to perform their traditional military obligation, which they did with their traditional inefficiency. In England, however, a long history of argument over the feudal obligation with respect to service overseas, that is, in defense of the king’s French lands, had prepared the way for a new departure. Borrowing heavily from Italian bankers against the lucrative royal wool tax,

11

Edward appointed captains to enroll and train paid “retinues” of archers and men-at-arms, both captains and retinues secured by “indenture”—contract. The resulting professional army not only triumphed on the battlefield at Crécy, but achieved something considerably more difficult by capturing the important port city of Calais. Large battles were rare in the Middle Ages, and though often tactically decisive, that is, ending in the destruction of the losing army (typically 20 to 50 percent killed, according to a modern scholar),

12

they rarely had an equivalent strategic or political effect. Calais was taken only after a siege of nearly a year, an extraordinary medieval military effort. Its capture was of great economic value to Edward as a port for the wool trade with Flanders, but it also provided an easy entry into northern France for expeditionary forces from England.

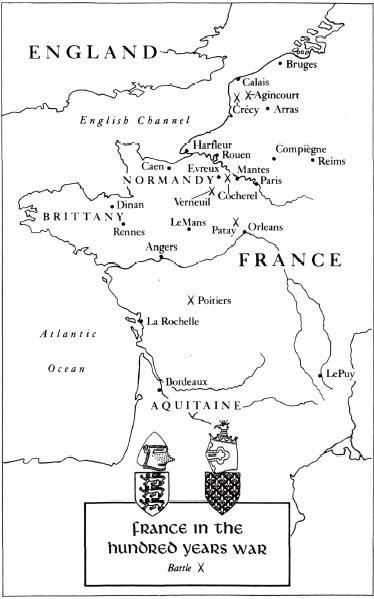

FRANCE IN THE HUNDRED YEARS WAR

A few months after Crécy, the English won a smaller battle in Brittany. At La Roche-Derrien casualties were very heavy on both sides, and Charles de Blois, commanding his army in person, and many times wounded, was taken prisoner. His stubbornly valiant wife, Jeanne, set about raising his ransom while continuing the war.

Bertrand du Guesclin, though not present at the battle, had already followed the example of his father and uncles in embracing the cause of Jeanne and Charles de Blois. Froissart lists him among the “good knights and squires” who repelled an English attack on Rennes in 1343,

13

but otherwise his early career in arms is obscure, with no further mention by Froissart or any other chronicler. Yet there is no reason to doubt Cuvelier’s picture of young Du Guesclin at the head of a guerrilla band operating from the fastness of Broceliande, a forest southwest of Rennes whose mysterious enchantments are celebrated in the tales of the Round Table. Apparently he received no stipend from Charles de Blois, but depended for supply on the support of the local peasantry, from among whom he recruited his followers, and whom he equipped—horses, arms, armor—in part by purloining his mother’s jewelry.

14

He made restitution thanks to an adventure more in the character of Pancho Villa than in that of Sir Lancelot. Ambushing three English soldiers carrying a chest of gold coins destined by Edward III for his garrison in the castle of Fougeray, he killed all three with his axe.

15

On a visit to his mother, he told her (according to Cuvelier), “Madame my mother, please pardon the thefts I’ve sometimes committed against you….” And for each penny taken he returned twenty shillings.

16

CASTLE OF MONTMURAN, NEAR RENNES, BRITTANY, IN WHOSE CHAPEL DU GUESCLIN WAS KNIGHTED IN

1354.

Emboldened, the young guerrilla chief determined to attempt the capture of Fougeray itself. For his small band neither siege nor assault was practicable, and so he had recourse to a third classic method: ruse. Choosing a moment (summer of 1350) when a part of the garrison was on a combat mission elsewhere, he enlisted the aid of the local inhabitants to disguise half his troops as peasants bringing firewood to the castle. Some concealed their weapons under women’s skirts and hid their beards in sunbonnets. When the drawbridge was lowered, Du Guesclin was the first to leap across it and attack the sentries. The gate was won, but the castle’s defenders rallied and the attackers were themselves hard pressed when a fresh reinforcement of horsemen made a timely arrival.

17

Du Guesclin was not strong enough to hold Fougeray, which was retaken in 1352 by Robert Knowles, a famous English captain and one of Du Guesclin’s lifelong adversaries. Meantime, Du Guesclin profited from the news of his exploit in gathering fresh recruits, even including a few knights proud to serve under so redoubtable a squire. In 1354 Du Guesclin was himself tardily knighted. In the previous three years both his mother and father had died, giving him as oldest son a modest inheritance. To his success as guerrilla chief he had added laurels as a champion in tournaments in Pontorson, and in April 1354 a new feat of arms provided the occasion for his knighting. The Sire d’Audrehem, marshal of the king of France and royal lieutenant for the Breton-Norman frontier, was invited to dinner on Holy Thursday by the Lady of Tinteniac in her castle of Montmuran. Hugh of Calveley, an English captain famed for his giant stature, planned to ambush d’Audrehem and his party, but Du Guesclin, getting wind of the affair, organized a counterambush, and in the resulting fracas Calveley and a hundred others were captured. One of the lords present, Eslatre des Mares, castellan of Caux, conferred knighthood on the hero of the encounter.

18

By this time, mid-fourteenth century, the honor was perfunctorily accepted as their due by the few youths of the upper nobility, but for the numerous sons of the lesser nobility to which Du Guesclin belonged it was no such matter of course. Du Guesclin was thirty-four by the time he achieved it. Cost was more than ever an obstacle to many poor or landless squires. As a squire, a man had a good chance of having his needs taken care of, his horse and equipment furnished. As a knight, he would be expected to furnish himself with not one but three horses, and in addition to equip his own squire, with the total cost running into hundreds of pounds (livres).

In recompense, the title of knight offered some material benefits. The English system of hiring soldiers was gradually spreading, and a knight ordinarily commanded double the pay of a squire—about 15 shillings (sous) per day compared with seven and a half.

19

A knight was also entitled to a larger share of booty and ransoms. More important to Du Guesclin, the knightly title was still virtually indispensable to a leader.