The Knight in History (30 page)

Read The Knight in History Online

Authors: Frances Gies

That Fastolf was not long in disfavor with Bedford is demonstrated by the fact that his career continued as before. The year after the disaster of Patay (1430), he was named governor of Caen, and in 1433, when the Burgundians opened lengthy negotiations with Charles VII at Arras and the English were forced to join in, Fastolf was sent by Bedford as a plenipotentiary. On September 9, 1435 the English withdrew from the parleys; on the fourteenth Bedford, taken suddenly ill, died. Fastolf was an executor of his will. A few days later, the French and Burgundians concluded a treaty by which the duke of Burgundy recognized Charles VII as king of France and withdrew from the war. The English garrisons in the Paris region were left isolated. During the winter most of the lesser places fell, and in April 1436 Paris went over to Charles VII. Fastolf’s old comrade-in-arms, Lord Willoughby, surrendered the Bastille and led the English garrison to Rouen.

While he was at Arras, Fastolf submitted a memorandum to Henry VI’s council at Rouen giving his views as Bedford’s chief lieutenant and military adviser.

He began by explaining the English decision to withdraw from the negotiations at Arras. Henry VI could not give up his claim to the French crown without admitting that his ancestors “had no right to the crown of France, and that all their wars and conquest hath been but usurpation and tyranny.”

*

If their cause had been wrong, he asked plaintively, would God have given them so many victories? Furthermore, the French had never kept their treaties but had set them aside “by colored dissimulations and deceits.” Therefore, the king must continue to press his claim, despite the opposition of the people of the occupied area of France, “who naturally love his adversary more than him.”

He went on to propose that long sieges should be abandoned as wasteful of time, personnel, and money. No leader could conquer a great kingdom by continual sieges, considering the advanced character of the equipment and weapons of the day and the enemy’s knowledge and experience of them. The king should therefore organize two armies of “about 750 lances” (3,000 men) led by “two notable chieftains, discreet and of one accord,” to go on parallel expeditions, joining forces if necessary. These armies should land at a Channel port, either Calais or Le Crotoy, on the first day of June, and continue their campaign until the first of November, making their way “through Artois and Picardy, and so through Vermandois, Laonnais, Champagne, and Burgundy, burning and destroying all the land as they pass, both house, grain, vine, and all trees that bear fruit for man’s sustenance, and all cattle that may not be driven to be destroyed; and those that may be well driven and spared in addition to the sustenance and victualling of the army, to be driven into Normandy, to Paris, and to other places in the king’s obedience.” Traitors and rebels (in other words, the population of the occupied area) must be treated to a “more sharp and cruel war” than ordinary enemies, or shortly no one would be afraid to rebel. The king might undertake “all this cruel war” without any accusation of tyranny, since he had offered his adversaries “as a good Christian prince” the opportunity of peace, “which offer the said adversaries have utterly refused.”

30

The report had two principal thrusts: first, it recommended a strategy in which the English concentrated on the defense and retention of Normandy, abandoning at least temporarily efforts to extend their conquests; second, it advocated clearing a wide band of territory of all that might be useful to the enemy and discouraging the inhabitants from aiding the French army.

31

Fastolf’s report has been cited as a statement of a policy created, in the words of a modern historian of the Hundred Years War, by “that old vulture Sir John Fastolf.”

32

In reality the English had already been reduced to a defensive strategy before the treaty of Arras, while the “scorched earth” recommendation was no more than a candid description of the old English tactic of the

chevauchée

(which, contrary to Fastolf’s conviction, had proved a failure). Indeed, it describes traditional medieval warfare in general, and is perhaps militarily most notable for its lack of appreciation of gunpowder artillery, which was on the point of revolutionizing siege warfare. On the expiration of the ten-year truce of Arras, the French rapidly reduced the English strongholds of Normandy and Gascony and won the war by the very siege methods Sir John Fastolf had condemned as futile.

On the philosophical plane, the Hundred Years War dramatized as never before the fundamental ambivalence of knightly attitudes. The glorification of knighthood continued to be the theme of Froissart and other chroniclers and poets as well as the object of the new secular military orders such as the Garter, while the elaborate tournaments staged by Edward III and others kept alive the pageantry of Arthurian romance. Even on the field of battle the archaic concept of war as sport was not totally dead. During the Christmas truce of 1428 at the siege of Orleans, English and Burgundian knights jousted with their French enemies, as in the previous century.

33

In the French attack on the English redoubt at Orleans, a Spanish man-at-arms, Alfonso de Partada, called to a French knight to join him in guarding the rear of the assault column. The knight refused, saying that it was dishonorable to take a post in the rear. An argument ended with the two agreeing “to ride together side by side against the enemy, to prove which was the more valiant.” Clasping hands, they galloped straight up to the English fortification.

34

The other side of the coin was the perception of war as a free-enterprise business undertaking, its aim the capture of wealthy prisoners for ransom (but merciless slaughter of the less favored), pillage of churches and monasteries, and the robbery and torture of peasants.

An enlightening summation of the contemporary attitude is a book written by a cleric, Honoré Bouvet,

*

late in the fourteenth century.

35

Copied over and over, the

Tree of Battles

was widely read by the knightly class. Arthur de Richemont, constable of France in the final stage of the war, his adversary Sir John Talbot, and many other commanders on both sides owned copies. The book was often cited in military courts and by other writers.

36

The poet Christine de Pisan incorporated large extracts into her

Book of Feats of Arms and of Chivalry

, selections from which William Worcester translated into English for Fastolf.

37

Bouvet adapted the

Tree of Battles

from a treatise by another cleric, John of Legnano, written in the context of fourteenth-century Italy, amid whose warring city republics the mercenary captains

(condottieri)

enjoyed even freer play than did their counterparts in France. Both authors drew on the unwritten “law of arms” that over centuries the knightly class had accumulated for division of booty and fixing of ransom, but their main discourse was pitched on a higher plane. Its concern was not the individual knight but the community.

38

In Bouvet’s eyes, war was natural and inevitable, but its evils and injustices were largely the result of “false usage, as when a man-at-arms takes a woman and does her shame and injury, or sets fire to a church.”

39

Wars should be conducted properly, ransoms should be “reasonable and not such as to disinherit [the captive’s] wife, children, relations, and friends” the man who exacted more was “no knight.”

40

Civilian populations should be respected, for “the business of cultivating grain confers privileges on those who do it.…In all wars poor laborers should be left secure and in peace, for in these days all wars are directed against the poor laboring people and against their goods and chattels. I do not call that war, but it seems to me to be pillage and robbery. Further, that way of warfare does not follow the ordinances of worthy chivalry or of the ancient custom of noble warriors who upheld justice, the widow, the orphan, and the poor.”

41

Here Bouvet reiterated the adjurations of the Peace of God of four hundred years earlier, but elsewhere he laid down rules that reflected the needs of contemporary military commanders. A knight must accept discipline. He must not attack without orders, though it was a “plain and notorious fact that a young knight received more praise for attacking than for waiting.”

42

Boldness might win “the vainglory of this world,” but a knight should be bold only through “right knowledge and understanding.”

43

A knight must be loyal first to the king, next to his lord, and next to the captain “who is acting in place of his lord as governor of the host.”

44

He should not separate himself from the main battle to challenge a foe in single combat “to show [his] great courage.”

45

In fact, he should “go nowhere at all” without his lord’s permission.

46

He must remember precisely that he was not a knight-errant but a professional soldier, a man who “does all that he does as a deputy of the king or of the lord in whose pay he is.”

47

Thus the popular vade mecum of the late medieval knight reinforced the old Christianizing ideals of the Round Table but to them added the iron demands of the modern army.

In 1440, after five more years in Normandy, Fastolf returned to England. He had made visits before, but this time he came to stay. He was sixty years old, and his military career was over, though he continued to serve the king as a member of the privy council.

He was rich. An evaluation of the receipts of his estates in 1445 brought the income from his English properties to an estimated £1,061, almost three-quarters of it from lands he had bought with his war profits. In addition, his properties in Normandy and Maine included ten castles, fifteen manors, and an inn at Rouen. Most had been granted by Henry V and Bedford, some in lieu of cash payment. Some had been purchased. Together they had at one time brought him an annual income of more than £675, but with the faltering English fortunes in France they now yielded only £401, a revenue that over the next few years dwindled and disappeared.

48

He also engaged in commerce, reverting to his grandfather’s métier. He owned several ships that plied between Great Yarmouth, London, and other east-coast ports and sometimes crossed to France, carrying wheat, barley, malt, raw wool, cloth, fish, and bricks. His manors produced wool, which he sold, and on at least one occasion he speculated in grain and made a killing.

49

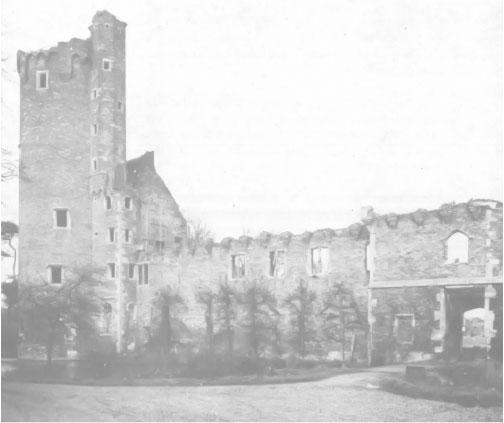

CAISTER CASTLE, BUILT BY SIR JOHN FASTOLF OVER A PERIOD OF TWENTY-FIVE YEARS, WAS CONSTRUCTED OF NATIVE BRICK. DOMINATED BY A ROUND TOWER NINETY-EIGHT FEET HIGH, IT HAD TWENTY-SIX BEDROOMS.

(HALLAM ASHLEY)

He owned fine houses not only in Norwich and Great Yarmouth but in Southwark, south of London Bridge, where presently he bought the Boar’s Head Inn. His most impressive possession, however, was Caister Castle. While he was still engaged in the fighting in France, he had begun to build, on the site of the manor where he was born, a splendid structure containing twenty-six bedrooms, a chapel, a moat, and a great round tower ninety-eight feet high. The design was that of contemporary Dutch and German castles. Built of brick manufactured on the spot, Caister was embellished by stone from France, conveyed to the site by a canal that passed under an arch into the walled enclosure. Timber was brought from Fastolf’s manor of Cotton, in Suffolk. On the wall of the Great Hall was carved the owner’s coat of arms, a bush of feathers supported by two angels, each with four wings, the whole encircled by the Garter, with the motto, “

Me faut faire

”—“I must be doing.” The castle was not completed until 1454, when Fastolf moved in, to remain until his death.

50

The old soldier lived in style. An inventory of his clothing and furnishings at Caister in 1448 includes gowns of cloth of gold and satin, jackets of velvet, leather, and fine camlet wool, linen doublets and petticoats, silk bed canopies, fine horse trappings of scarlet cloth with red crosses and roses, silk surcoats embroidered with Fastolf’s armorial bearings to be worn over armor, cushions of silk and velvet, numerous costly tapestries, featherbeds, silk coverlets, mattresses, candlesticks, bolts of cloth—damask, linen, embroidered silk and satin—silver dishes, some chased or with enameled or gilt decorations, silver saltcellars and basins, brass and copper pots and tubs. He owned gold and silver plate worth several thousand pounds.

21

He wore “daily about his neck” a gold cross and chain valued at £200, but his most valuable jewel was a “great pointed diamond set upon a rose enamelled white,” incorporated in “a very rich collar called…a White Rose.”

52

This ornament, worth the huge sum of 4,000 marks, had been given to Fastolf, along with other jewels, by Richard, duke of York, partly to repay a loan and partly to reward him for “the great labours and vexations sustained by the said knight for the said duke while he was the king’s lieutenant in France and later in England.”

53