The Italian Renaissance (16 page)

Read The Italian Renaissance Online

Authors: Peter Burke

The status associated with the roles of artist and writer was problematic. The problem was a special case of the more general difficulty of accommodating in the social structure, as the division of labour progressed, all roles other than those of priest, knight and peasant – those who prayed, fought and worked – the ‘three orders’ officially recognized in the Middle Ages.

88

If the status of an artist was ambiguous, so was that of a merchant. And just as Italians, in some regions at least, had gone further towards the social acceptance of the merchant than had most other Europeans, so it was in Italy that the status of the artist seems to have been at its peak. In the discussion that follows, the evidence of high status comes first, then the evidence of contempt and, finally, an attempt to reach a balanced conclusion.

Artists regularly declared that they had or ought to have a high status. Cennini at the beginning of the period and Leonardo towards the end both compared the painter with the poet, on the grounds that painter and poet alike use their imagination, their

fantasia

. Another point in favour of the high status of painting, and one which reveals something of Renaissance assumptions or mentalities, was that the painter could wear fine clothes while he was at work. As Cennini put it: ‘Know that painting on panel is a gentleman’s job, for you can do what you want with velvet on your back.’ And Leonardo: ‘The painter sits at his ease in front of his work, dressed as he pleases, and moves his light brush with the beautiful colours … often accompanied by musicians or readers of various beautiful works.’

89

In his

treatise on painting, Alberti offered several more arguments which recur during the period, such as the argument that painters need to study liberal arts such as rhetoric and mathematics and the argument from antiquity – that in Roman times works of art fetched high prices, while distinguished Roman citizens had their sons taught to paint, and Alexander the Great admired the painter Apelles.

Some people who were not artists seem to have accepted the claim that painters were not ordinary craftsmen. The humanist Guarino of Verona wrote a poem in praise of Pisanello, while the court poet of Ferrara dedicated a Latin elegy to Cosimo Tura and Ariosto praised Titian in his

Orlando Furioso

(more exactly, he inserted the praise of Titian into the 1532 edition of his poem). St Antonino, archbishop of Florence, noted that, whereas in most occupations the just price for a piece of work depends essentially on the time and materials employed, ‘Painters claim, more or less reasonably, to be paid the salary of their art not only by the amount of work, but more in proportion to their application and greater expertness in their trade.’

90

When the ruler of Mantua gave Giulio Romano a house, the deed of gift opened with a firm statement of the honour due to painting: ‘Among the famous arts of mortal men it has always seemed to us that painting is the most glorious (

praeclarissimus

) … we have noticed that Alexander of Macedon thought it of no small dignity, since he wished to be painted by a certain Apelles.’

91

A few painters achieved high status according to the criteria of the time, notably by being knighted or ennobled by their patrons. Gentile Bellini was made a count by the emperor Frederick III, Mantegna by Pope Innocent VIII, and Titian by the emperor Charles V. The Venetian painter Carlo Crivelli was knighted by Prince Ferdinand of Capua; Sodoma by Pope Leo X; Giovanni da Pordenone by the king of Hungary. For the patron it was a cheap way of rewarding service, but for the artist the honour was real enough. Some painters held offices which conferred status as well as income. Giulio Romano held an office at the court of Mantua, while the painters Giovanni da Udine and Sebastiano del Piombo held office in the Church. (Sebastiano’s nickname, ‘the lead’, was a reference to his office as Keeper of the Seal.) Other painters held high civic office. Luca Signorelli was one of the priors (aldermen) of Cortona; Perugino, one of the priors of Perugia; Jacopo Bassano, consul of Bassano; Piero della Francesca, a town councillor of Borgo San Sepolcro.

Again, a few painters are known to have become rich. Pisanello inherited wealth, but Mantegna, Perugino, Cosimo Tura, Raphael, Titian, Vincenzo

Catena of Venice and Bernardino Zenale of Treviso all seem to have become rich by their painting. Wealth gave them status, and the prices they commanded show that painting was not held cheap.

The testimony of Albrecht Dürer carries considerable weight. On his visit to Venice he was impressed by the fact that the status of artists was higher than in his native Nuremberg, and he wrote home to his friend the humanist patrician Willibald Pirckheimer, ‘Here I am a gentleman, at home a sponger’ (

Hie bin ich ein Herr, doheim ein Schmarotzer

).

92

In Castiglione’s famous dialogue, one of the speakers, Count Lodovico da Canossa, declares that the ideal courtier should know how to draw and paint. A few sixteenth-century Venetian patricians, notably Palladio’s patron Daniele Barbaro, actually did do this.

93

There is similar evidence for the status of sculptors and architects. Ghiberti’s programme of studies for sculptors, and Alberti’s for architects, implies that these occupations are on a level with the liberal arts. Ghiberti suggested that the sculptor should study ten subjects he calls ‘liberal arts’: grammar, geometry, philosophy, medicine, astrology, perspective, history, anatomy, design and arithmetic. Alberti advised architects to build only for men of quality, ‘because your work loses its dignity by being done for mean persons’.

94

The patent issued in 1468 by Federigo da Montefeltro, the ruler of Urbino, on behalf of Luciano Laurana declares that architecture is ‘an art of great science and ingenuity’, and that it is ‘founded upon the arts of arithmetic and geometry, which are the foremost of the seven liberal arts’.

95

A papal decree of 1540, freeing sculptors from the need to belong to the guilds of ‘mechanical craftsmen’, remarked that sculptors ‘were prized highly by the ancients’, who called them ‘men of learning and science’ (

viri studiosi et scientifici

).

96

Some sculptors, Andrea il Riccio of Padua for example, had poems addressed to them. Some were ennobled. The king of Hungary, Matthias Corvinus, not only made Giovanni Dalmata a nobleman but gave him a castle as well. Charles V made Leone Leoni and Baccio Bandinelli knights of Santiago. Ghiberti’s work made him rich enough to be able to buy an estate complete with manor house, moat and drawbridge. Other prosperous sculptors and architects include Brunelleschi, the brothers da Maiano, Bernardo Rossellino, Simone il Cronaca of Florence, and Giovanni Amadeo of Pavia, while Titian was among the wealthiest of all artists. The houses of artists are a sign of their rising status – in par

ticular, the palaces of Mantegna and Giulio Romano at Mantua and of Raphael in Rome.

97

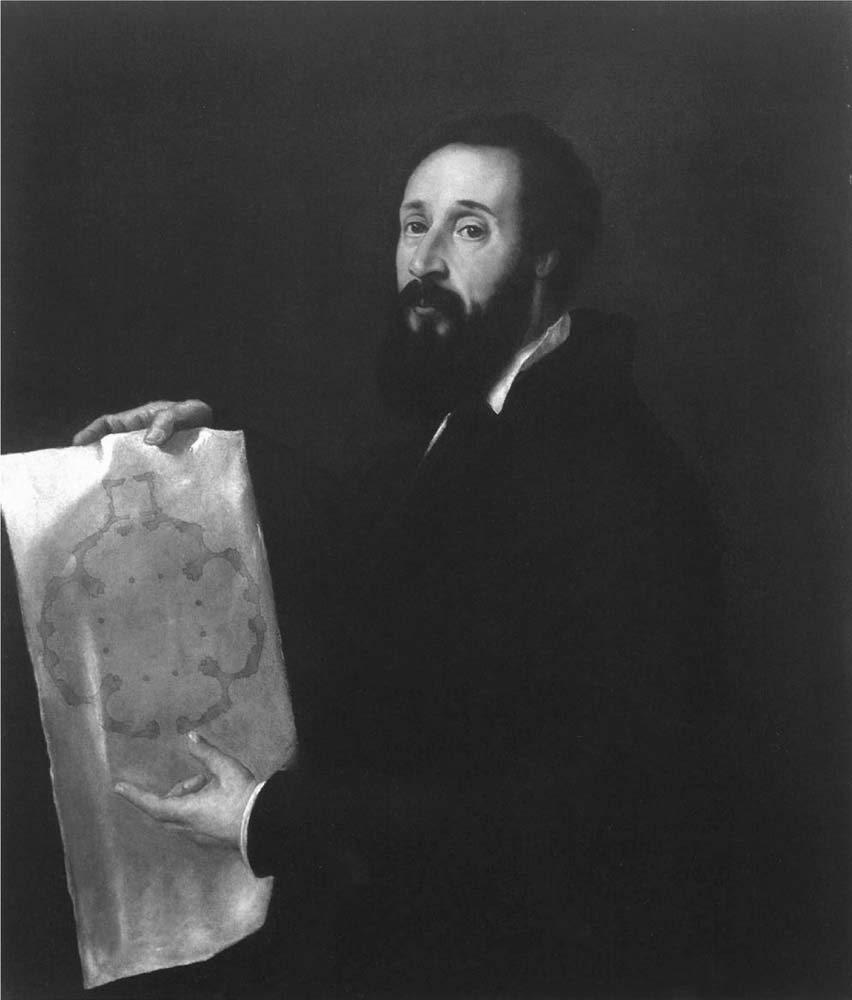

P

LATE

3.7 T

ITIAN

:

P

ORTRAIT OF

G

IULIO

R

OMANO

Composers of the period sometimes compared themselves to poets. Johannes de Tinctoris, who had impeccable credentials as an academic theorist of music, dedicated his treatise on modes to two practitioners, Ockeghem and Busnois – an unusual thing to do since the conventional view was that theory was the master and practice (composition no less than performance) merely

the servant. A number of composers were treated with honour in Italy at this time, although it is not easy to decide whether this was a tribute to their compositions or their performances (if indeed such a distinction was taken seriously at all). The humanists Guarino of Verona and Filippo Beroaldo wrote epigrams in praise of the lutenist Piero Bono, and medals were struck in his honour. Ficino and Poliziano wrote elegies on the death of the organist Squarcialupi, while Lorenzo de’Medici composed his epitaph and had a monument to him erected in the cathedral in Florence. Lorenzo’s son Pope Leo X made the lutenist Gian Maria Giudeo a count, while Philip the Handsome of Burgundy did the same for the Italian singer–composer Mambriano da Orto. The elaborate preparations made for the arrival of Jakob Obrecht in Ferrara show how highly he was prized by Duke Ercole d’Este. At the court of Mantua in the time of Ercole’s daughter Isabella, Marchetto Cara and Bartolommeo Tromboncino were honoured members of a musical circle. In Venice, Willaert, master of St Mark’s chapel, died rich, while Gioseffe Zarlino, another master of St Mark’s, had medals struck in his honour by the Republic and ended his days as a bishop.

98

A number of humanists also achieved high status. In the case of Florence, it has been argued that humanists belonged to the top 10 per cent of Florentine families. Leonardo Bruni, Poggio Bracciolini, Carlo Marsuppini, Giannozzo Manetti and Matteo Palmieri, for example, were all wealthy men. Bruni, Poggio and Marsuppini all held the high office of chancellor of Florence, while Palmieri held office at least sixty-three times and Manetti had a distinguished career as a diplomat and a magistrate. Of these five, three were born into the upper class, while Bruni (the son of a grain dealer) and Poggio (the son of a poor apothecary) entered it through their own efforts. All five made good marriages. Finally, Bruni, Marsuppini and Palmieri were all given splendid state funerals.

99

In case Florence was not typical, it may be useful to take a brief look at twenty-five humanists who were born outside Tuscany and active in the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries.

100

Of these twenty-five, at least

fourteen had fathers from the upper classes, while only three are definitely of humble origin (Guarino, Vittorino and Platina). Two were ennobled: Filelfo by King Alfonso of Aragon, Nifo by both Pope Leo X and Charles V. Three were famous university teachers: the lawyer Andrea Alciati, the philosopher Pietro Pomponazzi, and the literary critic Sperone Speroni. The Venetians Ermolao Barbaro and Andrea Navagero had distinguished political careers as senators and ambassadors. Angelo Decembrio, Antonio Loschi, Mario Equicola and Giovanni Pontano all held high administrative or diplomatic posts at the courts of Milan, Mantua and Naples. By worldly standards, almost all of them seem to have had successful careers.

There is, however, another side to the picture. Artists and writers were not respected by everyone. Some members of the elite whose achievements have been recognized by posterity had a difficult time of it in their own age. Three social prejudices against artists retained their power in this period. Artists were considered ignoble because their work involved both manual labour and retail trade and because they lacked learning.

To use a twelfth-century classification still current in the Renaissance, painting, sculpture and architecture were not ‘liberal’ but ‘mechanical’ arts. They were also dirty; a nobleman would not like to soil his hands using paints. The argument from antiquity, which Alberti had used in defence of artists, was actually double-edged, since Aristotle had excluded craftsmen from citizenship because their work was mechanical, while Plutarch had declared in his life of Pericles that no man of good family would want to become a sculptor like Phidias.

101

Leonardo’s vigorous protest against views like these is well known: ‘You have set painting among the mechanical arts! … If you call it mechanical because it is by manual work that the hands represent what the imagination creates, your writers are setting down what originates in the mind by manual work with the pen.’ He might have added the example of fighting sword in hand. Even Leonardo, however, shared the prejudice against sculptors: ‘The sculptor produces his work by … the labour of a mechanic, often accompanied by sweating which mixes with the dust and turns into mud, so that his face becomes white and he looks like a baker.’

102

The second point commonly made against artists was that they made a living from retail trade, so that they deserved the same low status as cobblers

and grocers. Noblemen, on the other hand, were ashamed to take money for their work. Giovanni Boltraffio, a Lombard nobleman and humanist who also painted, usually worked on a small scale, perhaps because he intended his pictures to be gifts for his friends, and his epitaph emphasized his amateur status. Leonardo threw this accusation, too, back into the faces of the humanists: ‘If you call it mechanical because it is done for money, who fall into this error … more than you yourselves? If you lecture for the schools, do you not go wherever you are paid the most?’

103

In practice, a distinction was often drawn between being on the payroll of a prince, which could happen to the best people, and keeping a shop. Michelangelo insisted strongly on this distinction: ‘I was never a painter or a sculptor like those who set up shop for that purpose. I always refrained from doing so out of respect for my father and brothers’ (this did not prevent him from being concerned with money).

104

In a similar manner Vasari, after years in Medici service, was able to refer with contempt to a minor painter, in his life of Perino del Vaga, as ‘One of those who keep an open shop and stand there in public, working at all sorts of mechanical tasks.’