The Italian Renaissance (12 page)

Read The Italian Renaissance Online

Authors: Peter Burke

However, the major innovators in the visual arts were often untypical of the group in their social origin. Brunelleschi (Plate 3.1), Masaccio and Leonardo were all the sons of notaries, while Michelangelo was the son of a patrician. Socially as well as geographically it was the outsiders, those with least reason to identify with local craft traditions, who made the greatest contribution to the new trends.

Training, like recruitment, suggests that artists and writers belonged to two different cultures, the cultures of the workshop and the university.

26

The painter Carlo da Milano is described in a document as ‘a doctor of arts’, while another painter, Giulio Campagnola, was a page at the court of Ferrara; but, in the overwhelming majority of cases, painters and sculptors were trained, like other craftsmen, by apprenticeship in workshops (

botteghe

) which were part of guilds that might include other kinds of artisan as well. In Venice, for instance, the guild of painters encompassed gilders and other decorators. At the beginning of our period, the process of apprenticeship was described as follows:

To begin as a shop-boy studying for one year, to get practice in drawing on the little panel; next, to serve in the shop under some master, to learn how to work at all the branches which pertain to our profession; and to stay and begin the working up of colours; and to learn to boil the sizes, and grind the

gessos

[the white ground used in painting]; and to get experience in gessoing

anconas

[panels with mouldings], and modelling and scraping them; gilding and stamping; for the space of a good six years. Then to get experience in painting, embellishing with mordants, making cloths of gold, getting practice in working on the wall, for six more years, drawing all the time, never leaving off, either on holidays or on workdays.

27

Thirteen years’ training is a long time, and it is probably a counsel of perfection. The statutes of the painter’s guild at Venice required a minimum apprenticeship of only five years, followed by two years as a journeyman, before a candidate could submit his ‘masterpiece’ and become a master painter with the right to open his own shop. All the same, painters were required to perform a wide variety of tasks in a variety of media (wooden panels, canvas, parchment, plaster, and even cloth, glass and iron), and it is scarcely surprising to find that they often started young. Andrea del Sarto was seven when he began his apprenticeship. Titian was nine, Mantegna and Sodoma ten. Paolo Uccello was already one of Lorenzo Ghiberti’s shop-boys when he was eleven. Michelangelo was thirteen when he was apprenticed to Ghirlandaio, and Palladio the same age when he began work as a stone-carver. Child labour was common enough in early modern Europe. From the contemporary point of view, Botticelli

and Leonardo left things a little late, for Botticelli was still at school when he was thirteen, while Leonardo was not apprenticed to Verrocchio until he was fourteen or fifteen. Artists did not have time for many years at school and most of them probably learned no more than a little reading and writing. Arithmetic, taught at the so-called abacus school, was considered an advanced subject leading to a commercial career.

28

Brunelleschi, Luca della Robbia, Bramante and Leonardo were probably exceptional among artists in attending schools of this kind.

Apprentices generally formed part of their master’s extended family. Sometimes the master was paid for providing board, lodging and instruction; Sodoma’s father paid the considerable sum of 50 ducats for a seven-year apprenticeship (on the purchasing power of the ducat, see

p. 230

below). In other instances, however, it was the master who paid the apprentice, at higher rates as the boy grew more highly skilled. Michelangelo’s contract with the Ghirlandaio workshop laid down that he was to receive 6 florins in the first year, 8 in the second and 10 in the third.

The fact that apprentices sometimes took their master’s name, as in eighteenth-century Japan, is a reminder of the importance of the master by whom an artist was trained. Jacopo Sansovino and Domenico Campagnola were not the sons but the pupils of Andrea Sansovino and Giulio Campagnola. Piero di Cosimo took his name from his master Cosimo Rosselli. It is in fact possible to identify whole chains of artists, each the pupil of the one before. Bicci di Lorenzo, for example, taught his son Neri di Bicci, who taught Cosimo Rosselli, who taught Piero di Cosimo, who taught Andrea del Sarto, who taught Pontormo, who taught Bronzino. The differences in individual style among these examples show that the Florentine system of cultural transmission was far from producing a traditional art. Again, Gentile da Fabriano taught Jacopo Bellini, who taught his sons Gentile (named after his old master) and Giovanni (who had a whole host of pupils, traditionally said to have included Giorgione and Titian).

A few workshops seem to have been of central importance for the art of the period: among Lorenzo Ghiberti’s pupils, for example, were Donatello, Michelozzo, Uccello, Antonio Pollaiuolo, and possibly Masolino, and among Verrocchio’s were not only Leonardo da Vinci but also Botticini, Domenico Ghirlandaio, Lorenzo di Credi and Perugino. The most important workshop in the whole period was probably that of Raphael, in which the pupils and assistants included Giulio Romano, Gianfrancesco Penni, Polidoro da Caravaggio, Perino del Vaga and Lorenzo Lotti (to be distinguished from Lorenzo Lotto). A recent study

speaks of Raphael’s ‘managerial style’. Michelangelo also made considerable use of assistants, of whom thirteen have been identified for the Sistine Chapel project alone.

29

An important part of the training of painters was the study and copying of the workshop collection of drawings, which served to unify the shop style and to maintain its traditions. A humanist described the process in the early fifteenth century: ‘When the apprentices are to be instructed by their master … the painters follow the practice of giving them a number of fine drawings and pictures as models of their art.’

30

Such drawings formed an important part of a painter’s capital, and might receive a special mention in wills, as they do from Cosimo Tura of Ferrara in 1471. Designs might be lettered in code because they were considered trade secrets, as in the case of a notebook from Ghiberti’s studio.

31

It is possible that, as deliberate individualism in style came to be prized more highly (above, p. 28), workshop drawings lost their importance. Vasari tells us that Beccafumi’s master taught him by means of ‘the designs of some great painters which he had for his own use, as is the practice of some masters unskillful in design’, a comment which suggests that the practice was dying out.

For humanists and scientists (and, to a lesser extent, writers, for ‘writer’ was a role played by amateurs), the equivalent of an apprenticeship was an education at a Latin school and a university (Plate 3.2).

32

There were thirteen universities in Italy in the early fifteenth century: Bologna, Ferrara, Florence, Naples, Padua, Pavia, Perugia, Piacenza, Pisa, Rome, Salerno, Siena and Turin. Of these universities, the most important in this period was Padua, where fifty-two members of the elite were educated, seventeen of them between 1500 and 1520. The growth of the university was encouraged by the Venetian government, in whose territory Padua lay. They increased the salaries of the professors, forbade Venetians to go to other universities, and made a period of study at Padua a prerequisite for office. It was convenient to have a university outside the capital. Lodgings were cheap, and the prosperity which the students brought with them helped to secure the loyalty of a subject

town. Padua also attracted students from other regions; of the fifty-two humanists and writers who attended the university, about half were born outside the Veneto. Students of scientific subjects (‘natural philosophy’, as it was called, and medicine) were attracted particularly to Padua. Of the fifty-three ‘scientists’ in the creative elite, at least eighteen studied there.

33

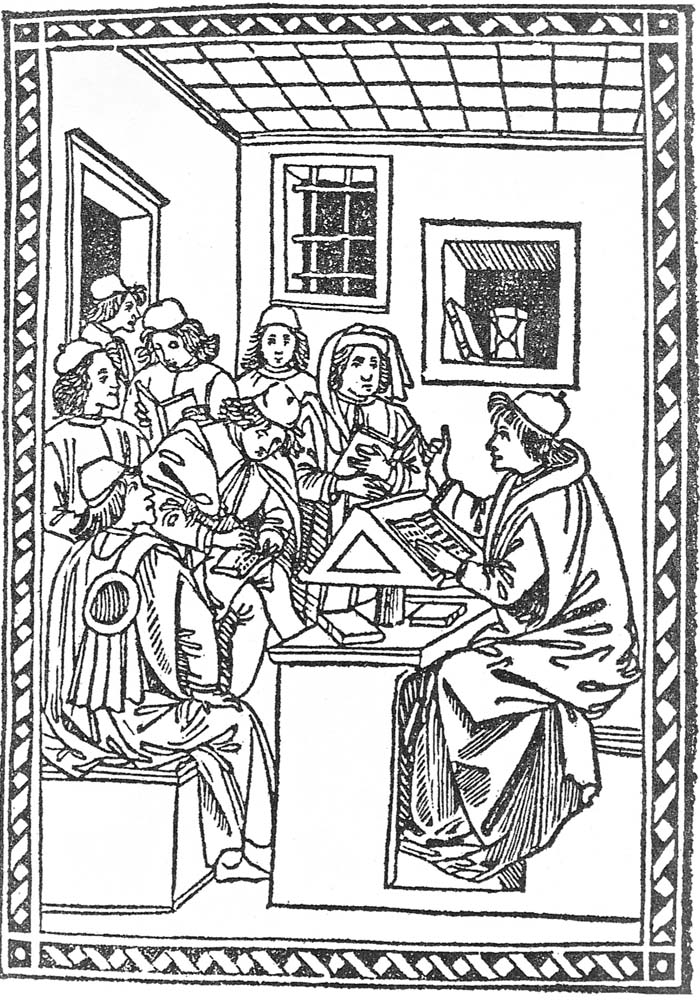

P

LATE

3.2 T

HE

T

RAINING OF A

H

UMANIST AT

U

NIVERSITY

, F

ROM C.

L

ANDINO:

F

ORMULARIO DI

L

ETTERE E DI

O

RATIONI

V

OLGARI CON LA

P

REPOSTA

, F

LORENCE

The next most popular university among the elite was Bologna, with twenty-six students. The senior university of Italy, Bologna had been through a decline, but it was reviving in the fifteenth century. Next came Ferrara, with twelve members of the elite. It had an international reputation for low fees; a sixteenth-century German student wrote that Ferrara was commonly known as ‘the poor man’s refuge’ (

miserorum refugium

).

34

Pavia (which serviced the state of Milan as Padua did Venice), Pisa (which serviced Florence), Siena, Perugia and Rome each accounted for about half a dozen of the elite. It is a pleasure to add that two of them (John Hothby and Paul of Venice) were Oxford men. Their colleges are not known.

Students tended to go to university younger than they do now; the historian Francesco Guicciardini was fairly typical in going up to Ferrara when he was sixteen. They began by studying ‘arts’ – in other words, the seven liberal arts, divided into the more elementary, grammar, logic and rhetoric (the

trivium

), and the more advanced, arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy (the

quadrivium

) – and proceeded to one of the three higher degrees in theology, law or medicine. The curriculum was the traditional medieval one, and officially nothing changed during the period. However, it is well known that what is taught at university – let alone what is studied – does not always correspond to what is on the curriculum. Research on British universities in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, based on the notes taken by students, has shown that a number of new subjects, including history, had been introduced unofficially. No equivalent study of Italian universities has yet been made, but there is reason to believe that what was described at the time as the ‘humanities’ (the

studia humanitatis

, the phrase from which our term ‘humanism’ is derived), a package of rhetoric, history, poetry and ethics, was coming to displace the

quadrivium

.

35

In some ways,

university students resembled apprentices. The disputation by means of which the bachelor became ‘master of arts’ was the equivalent of the craftsman’s ‘masterpiece’. A master of arts had the right to teach his subject, which was something like setting up shop on his own. However, teaching and learning, oral as well as written, took place in Latin, the symbol of a separate learned culture. Spies (

lupi

or ‘wolves’) ensured that the students spoke Latin even among themselves, and those who broke the rule were fined. Another obvious difference between apprentices and university students was the expense of training. It has been calculated that, in Tuscany at the beginning of the fifteenth century, it cost about 20 florins a year to keep a boy at a university away from home, a sum which would have kept two servants.

36

In addition, a new recruit to the doctorate would be expected to lay on an expensive banquet for his colleagues. The doctorate of civil law at Pisa which Guicciardini took in 1505 cost him 26 florins. Even the ‘poor man’s refuge’, Ferrara, was really the standby of the not so very well off.

Architects and composers need to be considered apart from the rest. Architecture was not recognized as a separate craft, so there was no guild of architects (as opposed to masons) and no apprenticeship system. Consequently, the men who designed buildings during this period had one curious characteristic in common – that they had been trained to do something else. Brunelleschi, for example, was trained as a goldsmith, Michelozzo and Palladio as sculptors or stone-carvers, and Antonio da Sangallo the elder as a carpenter, while Leon Battista Alberti was a university man and a humanist. There were, however, opportunities for informal training. Bramante’s workshop in Rome was the place where Antonio da Sangallo the younger, Giulio Romano, Peruzzi and Raphael learned how to design buildings; its importance in the history of architecture is something like that of Ghiberti’s workshop in Florence a hundred years earlier. Some famous architects, such as Tullio Lombardo and Michele Sammicheli, learned their trade from relatives.

37

Composers, as we call them, were trained as performers. A number of them went to choir school in their native Netherlands; Josquin des Près, for example, was a choirboy at St Quentin. The Englishman John Hothby taught music as well as grammar and arithmetic at a school attached to Lucca Cathedral which presumably catered for choirboys. Music (meaning the theory of music) was part of the arts course in universities, and several composers in the elite had degrees; Guillaume Dufay

was a bachelor of canon law, and Johannes de Tinctoris a doctor in both law and theology. There was no formal training in composition, but informally the circle of Johannes Ockeghem, in the Netherlands, was the equivalent of the workshops of Ghiberti and Bramante. Ockeghem’s pupils – to mention only those who worked in Italy – included Alexander Agricola, Antoine Brumel, Loyset Compère, Gaspar van Weerbeke, and probably also Josquin des Près. From Josquin there runs a kind of apostolic succession of master–pupil relationships which links the great Netherlanders to sixteenth-century Italian composers and the Italians to the major seventeenth-century Germans. Josquin taught Jean Mouton, who taught Adriaan Willaert (Plate 3.3), a Netherlander who went to Venice and taught Andrea Gabrieli, who, at the end of our period, taught his nephew Giovanni Gabrieli, who taught Heinrich Schütz.

38