The Italian Renaissance (13 page)

Read The Italian Renaissance Online

Authors: Peter Burke

To sum up. In Italy at this time there were two cultures and two systems of training: manual and intellectual, Italian and Latin, workshop-based and university-based. Even in the cases of architecture and music it is not difficult to identify the ladder which a particular individual has climbed. The existence of this dual system raises certain problems for historians of the Renaissance. If artists were such ‘early leavers’, how did they acquire the familiarity with classical antiquity that is revealed in their paintings, sculptures and buildings? And has the famous ‘universal man’ of the Renaissance any existence outside the vivid imaginations of nineteenth-century historians?

Contemporary writers on the arts were well aware of the relevance of higher education. Ghiberti, for example, wanted painters and sculptors to study grammar, geometry, arithmetic, astronomy, philosophy, history, medicine, anatomy, perspective and ‘theoretical design’.

39

Alberti wanted painters to study the liberal arts, especially geometry, and also the humanities, notably rhetoric, poetry and history.

40

The architect Antonio Averlino, who took the Greek name Filarete (‘lover of virtue’), wanted the architect to study music and astrology, ‘For when he orders and builds a thing, he should see that it is begun under a good planet and constellation. He also needs music so that he will know how to harmonize the members with the parts of a building.’

41

The ideal sculptor, according to Pomponio Gaurico, who wrote a treatise on sculpture as well as practising the art, should be ‘well-read’ (

literatus

) as well as skilled in arithmetic, music and geometry.

42

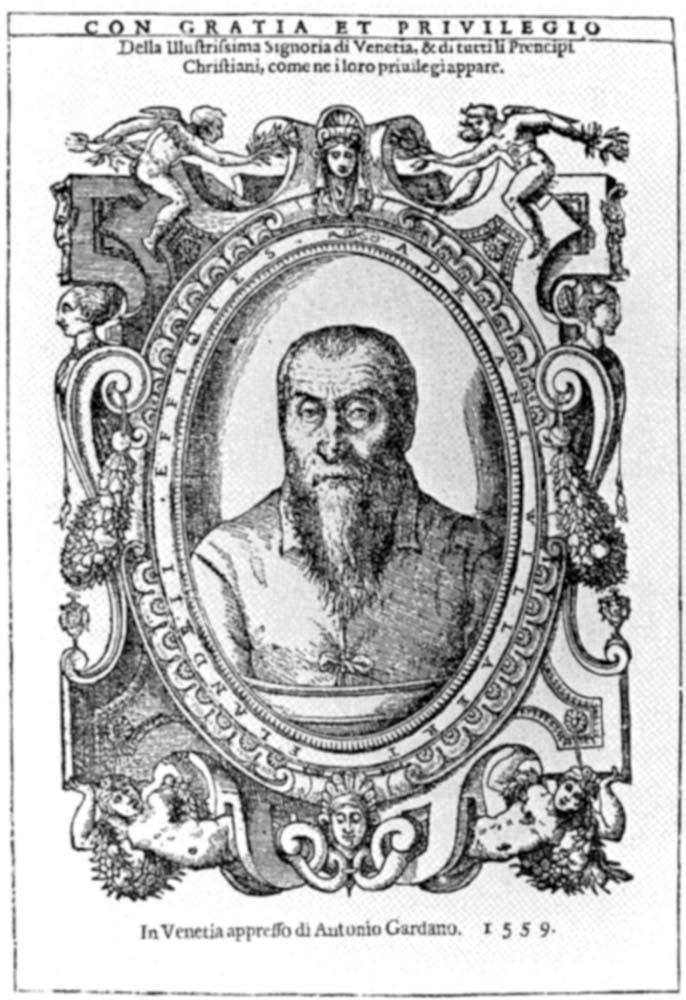

P

LATE

3.3 W

OODCUT OF

A

DRIAAN

W

ILLAERT

, F

ROM

M

USICA

N

OVA

, 1559

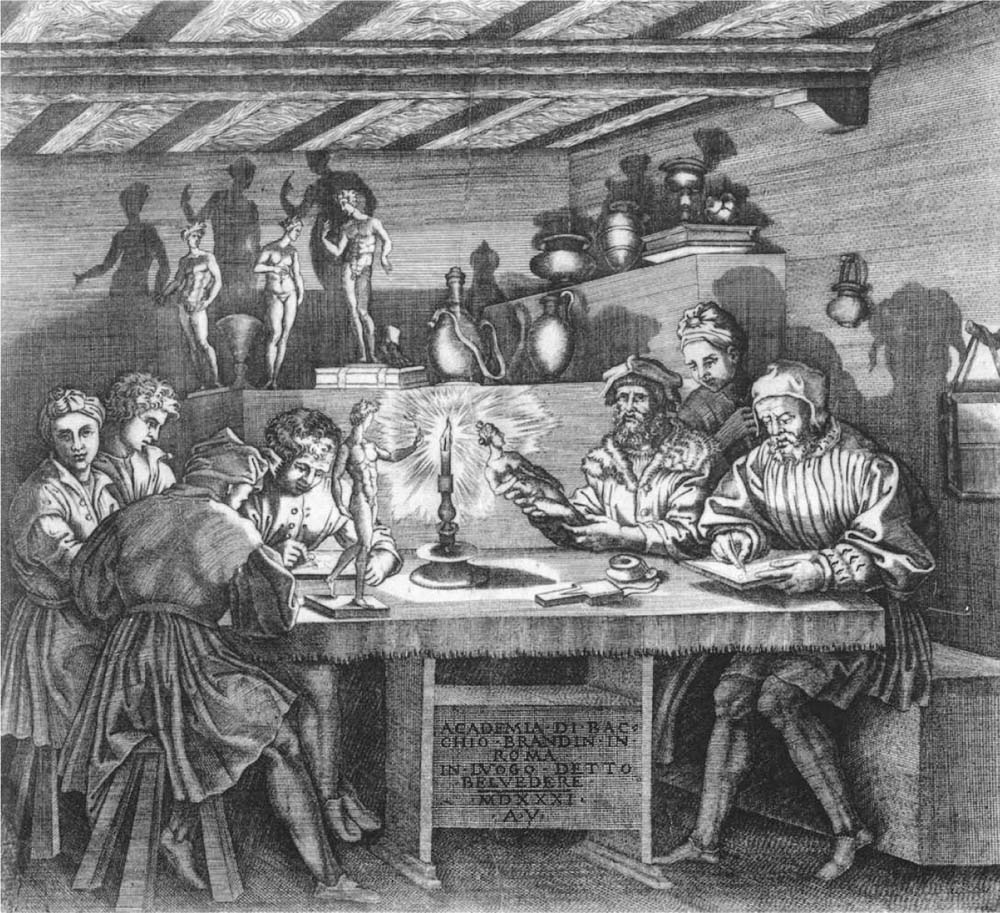

Did real

artists conform to this ideal? It used to be thought that the education many of them missed by leaving school early was provided for them in institutions called ‘academies’ (on the model of the learned societies of the humanists and ultimately of Plato’s Academy at Athens), notably in Florence, centring on the sculptor Bertoldo; in Milan, around Leonardo da Vinci; and in Rome, in the circle of the Florentine sculptor Baccio Bandinelli, whose pupils were portrayed studying by candlelight (Plate 3.4). However, there is no hard evidence of the formal training of artists in institutions of this kind until the foundation in 1563 of the Accademia di Disegno in Florence, the model for the academic system set up in seventeenth-century France, eighteenth-century England and elsewhere.

43

All the same, it should not be assumed that artists’ workshops of the Renaissance were empty of literary or humanistic culture. There was a tradition that Brunelleschi was ‘learned in holy scripture’ and ‘well-read in the works of Dante’.

44

Some artists are known to have owned books; the brothers Benedetto and Giuliano da Maiano, for example, Florentine sculptors, owned twenty-nine books between them in 1498. More than half of the books were religious: among them a Bible, a life of St Jerome and a book of the miracles of Our Lady. Among the secular books there were the two Florentine favourites, Dante and Boccaccio, as well as an anonymous history of Florence. Classical antiquity was represented by a life of Alexander and Livy’s history of Rome. The intellectual interests of the brothers revealed in this collection, traditional in orientation but with some tincture of the new learning, are not unlike those of Florentine merchants earlier in the century.

45

Artists with books like these in their possession were clearly interested in the classical past, and not only in its art, although that kind of interest can also be documented from inventories. At the time of his death in 1500, the Sienese painter Neroccio de’Landi owned several pieces of antique marble sculpture, together with forty-three plaster casts of fragments.

46

The most conspicuous absence from the library of Benedetto and Giuliano da Maiano is classical mythology. There is no copy of Ovid’s

Metamorphoses

or Boccaccio’s

Genealogy of the Gods

. Artists with such a library as theirs would have been more at home with religious paintings and sculptures than with the mythological paintings demanded by some

patrons. One wonders whether Botticelli, who was of the same generation, city and social origin as the da Maianos, had a collection of books very different from theirs. If not, then the role of a patron or his adviser must have been crucial in the creation of paintings such as the

Birth of Venus

or the so-called

Primavera

, and conversations are likely to have formed an important part of an artist’s education (cf. p. 116 below).

P

LATE

3.4 A

GOSTINO

V

ENEZIANO’S

E

NGRAVING OF

B

ACCIO

B

ANDINELLI’S

‘A

CADEMY’ IN

R

OME

That modest collection of books needs to be set in time. In 1498, printing had been established in Italy for a generation. It is unlikely that an artist could have amassed twenty manuscripts early in the fifteenth century. On the other hand, in the next century larger libraries are not uncommon. Leonardo da Vinci, sneered at in his own day as a ‘man without learning’ (

omo sanza lettere

), turns out to have had 116 books in his possession at one point, including three Latin grammars, some of the Fathers of the Church (Augustine, Ambrose), some modern Italian

literature (the comic poems of Burchiello and Luigi Pulci, the short stories of Masuccio Salernitano), and treatises on anatomy, astrology, cosmography and mathematics.

47

It would be unwise to take Leonardo as typical of anything, but there is a fair amount of evidence about the literary culture of sixteenth-century artists. The study of their handwriting offers some clues. In the fifteenth century, they tended to write in the manner of merchants, a style which was probably taught at abacus school. In the sixteenth century, however, Raphael, Michelangelo and others wrote in the new italic style.

48

Some artists, among them Michelangelo, Pontormo and Paris Bordone, are known to have gone to grammar school. The painter Giulio Campagnola and the architect Fra Giovanni Giocondo both knew Greek as well as Latin.

49

A few artists acquired a second reputation as writers. Michelangelo’s poems are famous, while Bramante, Bronzino and Raphael all tried their hands at verse. Cennini, Ghiberti, Filarete, Palladio and the Bolognese architect Sebastiano Serlio all wrote treatises on the arts. Cellini and Bandinelli wrote autobiographies, while Vasari is better known for his lives of artists than for his own painting, sculpture and architecture. It is worth adding that Vasari was able to bridge the two cultures by the happy accident of powerful patronage which gave him a double education – a training in the humanities from Pierio Valeriano as well as an artistic training in the circle of Andrea del Sarto.

50

These examples are impressive, but it is worth underlining the fact that they do not include all distinguished artists. Titian, for example, is absent from the list: it is unlikely that he knew Latin. In any case, the examples do not add up to the ‘universal man’ of the Renaissance. Was he fact or fiction? The ideal of universality was indeed a contemporary one. One character in the dialogue

On Civil Life

by the fifteenth-century Florentine humanist Matteo Palmieri remarks that ‘A man is able to learn many things and make himself universal in many excellent arts’ (

farsi universale di piu arti excellenti

).

51

Another Florentine humanist, Angelo Poliziano, wrote a short treatise on the whole of knowledge, the

Panepistemon

, in which painting, sculpture, architecture and music have their place.

52

The most famous exposition of the idea comes in count Baldassare Castiglione’s famous

Courtier

(1528), in which the speakers expect the perfect courtier to be able to fight and dance, paint and sing, write

poems and advise his prince. Did this theory have any relation to practice? The careers of Alberti (humanist, architect, mathematician and even athlete), Leonardo and Michelangelo are dazzling testimony to the existence of a few universal men, and another fifteen members of the elite practised three arts or more, among them Brunelleschi, Ghiberti and Vasari.

53

The humanist Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli (a friend of Alberti and Brunelleschi) also deserves a place in this company since his interests included mathematics, geography and astronomy.

54

About half of these eighteen universal men were Tuscans; about half had fathers who were nobles, professional men or merchants; and no fewer than fifteen of them were, among other things, architects. Either architecture attracted universal men or it encouraged them. Neither possibility is surprising, because architecture was a bridge between science (since the architect needed to know the laws of mechanics), sculpture (since he worked with stone) and humanism (since he needed to know the classical vocabulary of architecture). Apart from Alberti, however, these many-sided men belong to the tradition of the non-specialist craftsman rather than that of the gifted amateur. The theory and the practice of the universal man seem to have coexisted without much contact. The greatest of all, Michelangelo, did not believe in universality. At the time he was painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, he wrote to his father complaining that painting was not his job (

non esser mia professione

). He created masterpieces of painting, architecture and poetry while continuing to protest that he was just a sculptor.

For painters and sculptors, the fundamental unit was the workshop, the

bottega

– a small group of men producing a wide variety of objects in collaboration and a great contrast to the specialist, individualist artist of modern times.

55

Although distinctions were sometimes drawn between painters of panels and frescoes, on the one hand, and painters of furniture, on the other, one still finds Botticelli painting

cassoni

(wedding chests) and banners;

Cosimo Tura of Ferrara painting horse trappings and furniture; and the Venetian Vincenzo Catena painting cabinets and bedsteads. Even in the sixteenth century, Bronzino painted a harpsichord cover for the duke of Urbino. To deal with this wide variety of commissions, masters often employed assistants as well as apprentices, particularly if they worked on a large scale or were much in demand, as were Ghirlandaio, Perugino or Raphael. It is reasonably certain that Giovanni Bellini employed at least sixteen assistants in the course of his long working life (

c

. 1460–1516), and he may have used many more. Some of these ‘boys’ (

garzoni

) – as they were called irrespective of age – were hired to help with a particular commission, and the patron might guarantee to pay their keep, as the duke of Ferrara promised Tura in 1460 in contracting for the painting of a chapel.

56

Others worked for their master on a permanent basis, and they might specialize. In Raphael’s workshop, for example, which might be better described as ‘Raphael Enterprises’, Giovanni da Udine (Plate 3.5) concentrated on animals and grotesques.

57

The workshop was often a family affair. A father, for example, Jacopo Bellini, would train his sons in the craft. When Jacopo died he bequeathed his sketchbooks and unfinished commissions to his eldest son, Gentile, who took over the shop. Giovanni Bellini succeeded his brother Gentile, and was succeeded in turn by his nephew Vittore Belliniano. Again, Titian’s workshop included his brother Francesco, his son Orazio, his nephew Marco and his cousin Cesare.

58

The

garzoni

were generally treated as members of the family, and might marry their master’s daughter, as Mantegna and others did.