The Italian Boy (14 page)

Authors: Sarah Wise

Meanwhile, in the countryside, protest against the enclosure of farmland, against low wages, unemployment, and the corruption of many rural parochial authorities—in particular, those who administered relief for the poor—gave rise to widespread civil unrest. The Captain Swing riots—fourteen hundred incidents of arson, livestock-maiming, and damage to farm property—lasted throughout the summer and autumn of 1831, spreading across the whole of southern England, from Kent to Cornwall.

18

However, the lower classes contained elements within their own ranks that proved the most effective means of quashing unrest and maintaining the status quo. Before the 1824 Vagrancy Act, anyone—including a parish constable—apprehending a beggar had been entitled to a financial reward. One of the most despised figures was the local “vagrant collector,” such as John Conway of Highgate, who turned to the trade when his stay-making business collapsed. Conway was a prolific professional vagrant collector, receiving ten shillings from the parish upon the conviction of every beggar he apprehended and delivered to the magistrates.

19

The new act abolished these rewards—though many people were to remain unaware of this change in the law—but introduced fines of up to five pounds for any parish constable who failed to arrest a beggar. The belief that an apprehender of beggars was paid for turning in vagrants meant that there were plenty of dangers in undertaking such an arrest. The London Society for the Suppression of Mendicity employed a number of plainclothes officers, recruited from the lower-middle classes, to go into the streets to arrest suspected vagrants and bring them to the society’s offices, at 13 Red Lion Square, Holborn. (Residents of the square protested at the “numerous and tumultuous assemblage” that gathered outside the Dicity upon the sudden arrival of the very cold winter of 1830–31.)

20

Once there, the vagrant would be either handed over to the authorities (to magistrates for trial on vagrancy charges or to the appropriate parish for relief) or supplied with vouchers for cheese, potatoes, rice, bread, and soup—or, for a skilled worker, a loan with which to buy the tools of his trade. If a vagrant proved up to stone breaking or oakum picking when put to the test in the Dicity’s yard, he or she could be admitted to its very own poorhouse, whence around one in seven absconded. To qualify for relief, the claimant had to give a full account of his or her life—in effect, had to agree to be surveyed. This type of punitive snooping activity was loathed by the London poor, and Dicity officers were often attacked as they attempted to make arrests. One day in 1829, several hundred bystanders took the side of “MD,” a forty-two-year-old Irish woman who had traveled almost two hundred miles to London from Macclesfield with her four children, all of whom were visibly feverish. The Dicity had given her financial aid in the past and its officers attempted to arrest her when they spotted her begging once more, but they were prevented from taking her into custody by the crowd that gathered round.

21

(Even authority figures faced such hostility: one evening in 1829 a number of police officers attempted to rescue a senior London magistrate, Allan Laing, who had had to barricade himself inside a shop in Lambs Conduit Street, Holborn, when a crowd attacked him for attempting to make a citizen’s arrest on an itinerant match seller who had asked him “for a penny or two.” “Bonnet [punch] him! Bring him out!” shouted the crowd, after they had freed the beggar from Laing’s clutches, to loud cheers.

22

)

The Dicity produced annual reports praising its deeds of the past year and providing a statistical breakdown and anecdotal evidence of the “Objects” it had processed. Thus, the 1830 report gives the following picture of the 671 people detained by Dicity constables: 21 claimed to be impoverished because of old age, 6 cited business failure, 4 claimed to be foreigners who could not afford their fare home, 64 (mainly women) were destitute through loss—by death, desertion, or imprisonment—of a husband or close relative, 1 had lost everything in a fire, 1 had been shipwrecked, 61 had met with an accident or had suffered a serious illness, 4 had had their pay or pension suspended, 2 were ex-convicts who could not find anyone to vouch for their good name when seeking employment, 7 had no clothes in which they could decently seek work, another 7 had no tools with which to carry out their trade, 493 described themselves simply as “in want of employment.” Of the 671, only 156 described themselves as native Londoners; some 285 had come up to London from the English countryside in search of work; 127 were from Ireland; 28 were described as coming “from Europe,” regions unspecified; 28 were Scottish; 10 were Welsh; 7 were American; 5 were West Indian; 2 were from the East Indies; 2 were African; and a disproportionate 21 were Italian. The London parish most likely to be named as place of abode was St. Giles, the rotting slum—in the process of becoming a national embarrassment—just north of Covent Garden. Twice as many impoverished Londoners came from St. Giles as from the next two parishes on the list—St. Mary’s, Whitechapel, and St. Andrew’s, Holborn.

Since this data appeared in what was essentially a booklet appealing for funds, the attempt at categorization and quantification was no doubt supposed to impress potential sponsors. After the report’s figures come some brief notes on certain of the Dicity Objects of 1830:

“JT,” wife, four children, no job, good character, had sold all belongings and was begging;

“WR,” 38, a failed Oxford Street linen-draper with debts, friends helped but they were in trouble too, on the streets;

“MD”’s husband a long-term hospital patient, he had been a manservant, Irish, good character;

“WS,” 39, discharged lieutenant and now a failed artist, a wife, four children, starving in an empty garret with not even a bed;

“JG,” 39, a Manchester manufactory lad, induced to seek fortune in London, abandoned by his pals, he was returned to his grateful parents in Salford;

a failed umbrella maker, 31, of Liverpool, came to London but he and his wife and two children were begging in Covent Garden, could only get casual shifts at the dock;

“JH,” 27, of Birmingham, was found with a placard “Obligation! Myself, my wife and two children are nearly starving in a land of plenty! My wife wants bread, my children pine and cry, Kind reader, pray a mite impart as you pass by.”

23

The Dicity was a tantalizing mixture of narrow-minded judgmentalism punctuated by outbursts of compassion and even sentimentality; in its publications, skeptical comments about beggars’ claims of unemployment do battle with exclamations on how dreadful the state of the labor market had been of late. In 1830, one-third of vagrancy cases brought before London magistrates were the result of arrests made by Dicity workers.

24

The London Society for the Suppression of Mendicity had come into being not to help the poor but to ensure that as many vagrants were apprehended and prosecuted as the law allowed. The term used in its literature for the activities of its constables is “clearing the streets”—that is, seeing to it that public places were free from the sights, sounds, and smells of extreme poverty.

Many vagrants did nevertheless go to Red Lion Square of their own accord, to seek shelter, food, or safety. One such was a twelve-year-old native of Parma, in northern Italy, who had been seen around the streets of central London carrying a wax doll in a wooden box. He was in dreadful physical condition; his skin was covered in scabs, his eyes were infected—probably a result of scurvy—and his face was bruised. In April 1834 he went to the Dicity and told its officers that he was too frightened to go back to his lodgings in Vine Street, off Saffron Hill, in Little Italy. He said that he had been beaten by the man he worked for, Alexander Ronchatti, because he had failed to bring back enough money from his begging; Ronchatti also “employed” two other boys to go out into the street to beg, said the boy. When questioned through an interpreter, Ronchatti denied the boy’s story, saying that the child had absconded from his lodgings with the doll, which belonged to Ronchatti. The Dicity officer on duty claimed to have witnessed such a scene before, where an Italian running a troupe of beggar boys had used an interpreter to lie and cover up for him. However, Ronchatti was discharged, after being admonished via the interpreter. The boy was given into the care of the Italian ambassador’s staff. Only the doll was arrested—it was impounded by the Dicity, being worth three pounds.

25

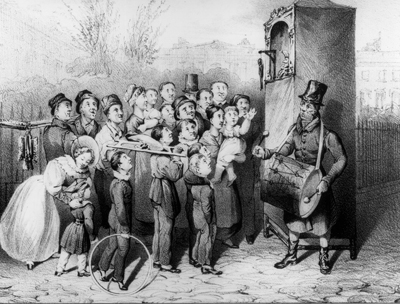

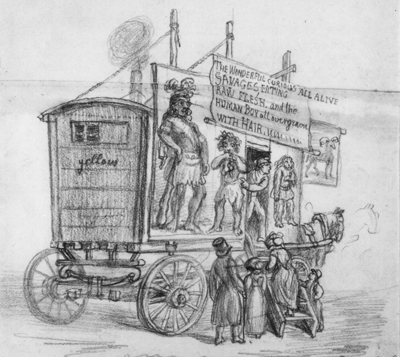

It was a telling incident. By the 1830s, a separate group of vagrant children had emerged, combining the role of entertainer and outcast and catering to that hunger for spectacle that saw people flock to the flimsiest, makeshift, unlicensed theatrical performances (“penny gaffs”) and to horse-drawn caravan shows featuring midgets, bizarre animals, waxworks, and people with unusual deformities—even to gawk at the oranges and pineapples and other exotic fruit when their season arrived at Covent Garden market.

26

To a population with little access to books or periodicals, and no access to parks, zoos, galleries, or museums—forbidden to them by price and by social exclusivity—Italian boys brought music, pathos, intriguing objects, and strange animals, plus, in many cases, their own physical beauty, to some of London’s grimmest streets. The imaginative life of the poor was kept from starvation by such humble food.

Caravan shows and puppet booths attracted adults as well as children, despite a crackdown on street noise and “nuisance” in London.

* * *

The economies of the Italian states

had been devastated by the Napoleonic Wars; some northern regions experienced famine in 1816 and 1817, while political repression was common in the disputed areas of Piedmont and Savoy, which bordered France. (Savoy would be ceded to France in 1860; Piedmont to Italy.) There was large-scale migration throughout the 1820s, with many Italian artisans moving to northern European cities to pursue their trades. In London, Italians were renowned for their skill in manufacturing optical devices—spectacles, telescopes, barometers—musical instruments, puppets, and waxworks. They introduced to Britain

fantoccini,

grotesque puppets in elaborate costume; grown men were observed to collapse into giggles at fantoccini performances in booths at street corners.

27

The wax and plaster artists, the

figurinai,

came mainly from Lucca in Tuscany and settled in Holborn and Covent Garden. While later in the century Italian street children would be known for playing instruments and dancing, until the mid-1830s their principal source of income was exhibiting small animals as well as wax and plaster figures. There was a good trade in silk or paper flowers to which wax birds were attached; busts of literary and theatrical greats, as well as military and naval heroes, would be transported on large trays carried on an image boy’s head, as a walking advertisement for the

figurinaio

who had created them, while an image boy’s

boîtes à curiosité

included anatomical wax models, notably a copy of a sketch of recently stillborn Siamese twins who had been dissected by anatomists. Let the rhymester responsible for “The Image Boy,” in the January 1829 issue of the

New Monthly Magazine

, explain:

Who’er has trudged, on frequent feet,

From Charing Cross to Ludgate Street,

That haunt of noise and wrangle,

Has seen on journeying through the Strand,