The Italian Boy (15 page)

Authors: Sarah Wise

A foreign Image-vendor stand

Near Somerset’s quadrangle.

His coal-black eye, his balanced walk,

His sable apron, white with chalk,

His listless meditation,

His curly locks, his sallow cheeks,

His board of celebrated Greeks,

Proclaim his trade and nation.

Not on that board, as erst, are seen

A tawdry troop; our gracious Queen

With tresses like a carrot,

A milk-maid with a pea-green pail,

A poodle with a golden tail,

John Wesley, and a parrot.

No, far more classic is his stock;

With ducal Arthur, Milton, Locke,

He bears, unconscious roamer,

Alcmena’s Jove-begotten Son,

Cold Abelard’s too tepid Nun,

And pass-supported Homer.

……………………

Poor vagrant child of want and toil!

The sun that warms thy native soil

Has ripen’d not thy knowledge;

’Tis obvious, from that vacant air,

Though Padua gave thee birth, thou ne’er

Didst graduate in her College.

’Tis true thou nam’st thy motley freight;

But from what source their birth they date,

Mythology or history,

Old records, or the dreams of youth,

Dark fable, or transparent truth,

Is all to thee a mystery.

But it wasn’t all poets and philosophers. Exhibiting creatures that were highly unusual to London eyes could prove lucrative too, and one Italian boy, “PG,” arrested by the Dicity in 1826 while entertaining a passerby with his dancing monkey, was found to be carrying £21 7s and 6d.

28

Beasts for display included white mice, guinea pigs, monkeys (uniformed or “naked”), tortoises, porcupines—even a marmot, a groundhog native to the mountains of the Savoy region. The objects and creatures were rented out to the boys each morning by the men who ran the trade, at these daily rates:

Box of wax Siamese twins | | 2s |

Organ with waltzing figures | | 3s 6d |

Porcupine | | 2s 6d |

Organ | | 1s 6d |

Organ plus porcupine | | 4s |

Monkey in a uniform | | 3s |

Monkey without uniform | | 2s |

Box of white mice | | 1s 6d |

Tortoise | | 1s 6d |

Monkey on a dog’s back | | 3s |

Four dancing dogs, in costume, with pipe and tabor | | 5s |

It was said that one happy outcome of the 1824 Vagrancy Act was a reduction in the practice of beggars waving their deformities in the face of the public; what had arisen in its place was an appeal to sympathy, with plaintive looks and an air of patient submission becoming more prevalent among those with a regular pitch. Italian boys were indeed pitiful—victims of organized child-trafficking by their fellow countrymen. The so-called

padroni

(“masters,” “owners,” or “employers,” also called

proveditori,

“providers”) paid a sum of money to impoverished peasants in rural, mainly northern Italy in return for the services of their son—a sort of beggars’ apprenticeship.

30

The parents were told that their child was being taken abroad to learn a trick or skill, usually theatrical in nature, which would earn him a living. The parents’ (dialect) term for their son’s fate was

“È peo mondo co a commedia,”

which translated as “He is wandering the world with a theater company”; in reality, once the child had been walked through France to England, he would find himself a virtual slave to his padrone.

The Italian boy trade stretched across Britain: Bristol, Birmingham, Liverpool, Manchester, Sheffield, Bradford, Glasgow, Brighton, and Worthing were all home to padroni. In London, whole houses in the Holborn area—in Saffron Hill, Vine Street, Eyre Street, Greville Street, Bleeding Heart Yard—as well as the streets around the southern end of Drury Lane were taken over by padroni, and boys were packed into dormitories, for which they were charged four pence a night. The animals belonged to the padroni, who joined into syndicates, owning

una zampa per uno

—“a paw apiece.” The boys, who often learned little English during their stay, were instructed to tell anyone who asked that the padrone was their uncle or much older brother and to provide false names for themselves and the padrone. Procuring a child to solicit alms was a breach of the Vagrancy Act, after all, but little action appears to have been taken against the padroni until certain notorious assaults and deaths later in the century.

31

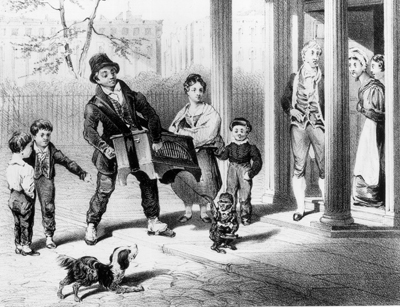

Some Italian boys exhibited exotic animals.

Londoners appear to have felt sentimental about Italian boys/image boys/white mice boys, with their dark, imploring eyes, sweet, melancholy expressions, and picturesque destitution. In a curious case in 1834, Lord Dudley Coutts Stuart, Whig member of Parliament and “champion of the oppressed” (according to his obituarists), announced that he would personally request the home secretary to secure the release of two Italian boys sentenced to two weeks in prison by magistrates White and Burrell at the Queen Square magistrates office, Holborn. Metropolitan Police constables Simpson and Brockway of B Division (Westminster) had arrested Antonio Loniski and Barnard Malvarham, both aged about fourteen, for begging in Wilton Street, Pimlico—close to Stuart’s residence—at three o’clock in the afternoon of Easter Monday; one boy had a monkey, the other a cage of white mice. The magistrates had jailed them for committing an offense under the Vagrancy Act, and the court sold off the animals to help pay the boys’ prison costs. On hearing the news, Stuart went straight to the Queen Square justices to explain that the boys had been two of a party of nine Italian entertainers invited by him to an Easter feast at his London home and that they had simply been waiting outside his house for the door to be answered. Stuart’s footman had told the constables this, he said, but they had still taken the boys into custody. Stuart failed to free the boys, and he left the court declaring his intention to petition Lord Melbourne for their release.

32

It is possible that Loniski and Malvarham were arrested, while the other seven Italians were not, because they were not playing instruments; if playing could be defined as “skilful,” the Vagrancy Act did not apply—or rather, it might have made a police officer unsure of his grounds for arrest. Displaying animals involved very little skill and left the child more vulnerable to arrest, which may be why from the 1840s on it was more common for Italian street children to play music and dance for money than exhibit animals. “If they are considered vagrants, they are the most inoffensive and amusing vagrants,” declared journalist Charles MacFarlane of Italian boys. “No offences or crimes are committed, despite their poverty and youth.” In any case, MacFarlane added, such entertainments were probably good for the lower orders, being instructive and educational: “They propagate a taste for the fine arts … and [their] animals may awaken an interest in natural history.” Fellow journalist Charles Knight agreed, writing in 1841, “We have some fears that the immigration of Italian boys is declining. We do not see the monkey and the white mice so often as we could wish to do.… What if he be but the commonest of monkeys? Is he not amusing? Does he not come with a new idea into our crowded thoroughfares, of distant lands where all is not labor and traffic? These Italian boys, with their olive cheeks and white teeth—they are something different from your true London boy of the streets, with his mingled look of cunning and insolence.”

33

Many Italian immigrants made a living as itinerant musicians.

All in all, Italy was providing London with a better class of vagrant. The pathos an Italian boy evoked could earn his master six or seven shillings a day. Dead—and apparently murdered to supply the surgeons—his appeal seemed only to increase.

FIVE

Systematic Slaughter

At daybreak on Saturday, 19 November, the body of the dead boy was exhumed. He had been buried (described in the register of burials as “A Boy Unknown”) on the eleventh in the graveyard of St. Pancras workhouse, which served as the spillover burial ground for St. Paul’s, Covent Garden, and was where the poorest of the parish were destined.

1

(Later, there would be criticism that the subject of an ongoing criminal case had been buried so swiftly, the

Lancet

medical journal pointing to the decision as one more example of the incompetence of coroners.) Augustine Brun, an elderly Birmingham-based padrone named by Joseph Paragalli as the dead boy’s master, had been brought to London to view the corpse. This, along with other new evidence that had come to light, so excited George Rowland Minshull that he convened a special hearing for the Italian Boy case at Bow Street, on Monday, 21 November. Joseph Paragalli acted as Brun’s interpreter to the magistrates.

Brun revealed that he had brought a boy called Carlo Ferrari to England from northern Italy in the late autumn of 1829; though from Piedmont, Carlo was a Savoyard, said Brun. His father, Joseph, had signed Carlo over to Brun for a fee. Brun had had charge of the boy for his first nine months in England, though Carlo had lodged at the house of another man, called Elliott, at 2 Charles Street, just south of Bow Street.

In the summer of 1830, Brun had bound Carlo over to a new master, an Italian called Charles Henoge who played the hurdy-gurdy and exhibited monkeys, for a period of two years and one month, and, as far as Brun knew, the new master had taken Carlo to Bristol. Carlo would now be about fifteen years old, Brun believed. (The

Globe and Traveller

newspaper report has Brun additionally claiming, “The poor boy ran away from his master about a year ago,” and that Carlo made sure that he left London whenever this particular padrone—presumably Henoge, though the newspaper does not make this clear—was rumored to be coming to the capital.)

2