The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself (14 page)

Read The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself Online

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

3.2 Brand Luther. The maturing Luther pamphlet highlights the elements most critical to its sale.

The Reformation brought about a large and sustained increase in the volume of books published in Germany. Eventually, however, the fires dimmed; the number of new titles dedicated to the Reformation controversies began to fall. This left a considerable gap in a greatly enlarged book market. The Reformation had created new classes of readers, men and women who had developed the habit of buying books for the first time. It had also greatly increased the number of printers working in Germany, including many in towns that had not previously been able to sustain a printing press. These men were inevitably eager to retain the new readers and sustain their new habit of investing precious income in books.

It is therefore no coincidence that the years when Reformation publishing fell from its peak witnessed a sharp rise in the numbers of other types of pamphlet

literature. Among these was a new type of news-book: the

Neue Zeitung

.

35

This was not, as the title might suggest, a newspaper. Although

Zeitung

has now become the German word for ‘newspaper’, this is a change of sense from its use in the sixteenth century.

Zeitung

derives from an earlier Middle -German word

zidung

, which is closest to the Dutch

tijding

or English ‘tiding’.

Neue Zeitung

is therefore best translated as ‘new tidings’ or ‘a new report’. Etymologically the word

Zeitung

on its own does not carry the same resonance of novelty or newness as the English word ‘news’ or the French

nouvelles

.

This raises the interesting issue of whether a report has to be of recent events in order for sixteenth-century readers to regard it as news. The answer seems to be that it very much depends on what is being reported. It was not unusual for news pamphlets to be re-published years, even decades after the events they described.

36

One interesting example is the rash of late fifteenth-century pamphlets (published between 1488 and 1500) celebrating the life and deeds of Vlad Dracula, the Impaler, who had died in 1476. These publications, stimulated by the contemporary concern at Turkish encroachment in eastern Europe, were really works of history dressed up as news pamphlets. Here a brutal warrior was reappropriated as a hero of Christian resistance to the Ottoman foe.

37

On other occasions news pamphlets do genuinely offer the first intimation of dramatic developments. Sometimes we are offered a ‘new report’ of an unfolding event: a siege, a campaign, or the meeting of a Council or Diet.

The

Neue Zeitungen

were comparatively brief texts, almost invariably continuous pieces of prose devoted to a single news report. This marks them out from the more varied digests of news presented in the merchant correspondence, or in the manuscript newsletters that would be the true ancestors of the newspaper.

38

This prose structure did, however, allow these news pamphlets to inform the public in some depth about the great issues of the moment. They first appear on the market in Germany in the first decade of the sixteenth century: the first

Neue Zeitung

that survives today dates from 1509.

39

They remain comparatively rare until at least the 1530s. In Germany the Luther affair had so overwhelmed interest in other types of news that printers had little reason to seek alternative markets. It was in the middle decades of the century that the news pamphlets first came into their own. In form and presentation the

Neue Zeitungen

were remarkably similar to the Reformation

Flugschriften

, from which they had clearly adopted important aspects of presentation. Almost without exception they were published in the quarto format favoured for German pamphlets, with a text of four or eight pages. Occasionally the front cover would be decorated with a woodcut illustration, usually a generic battle scene, seldom specially cut for the particular title. There was

scarcely ever any further illustration in the text. These texts were not then costly to produce. A quarto of four or eight pages was a single day's work for even a relatively small print shop. An edition of five or six hundred copies could be out on the streets within a day or two of the printer obtaining the text.

The news pamphlets proved immensely popular, both with the buying public and with publishers. Printers could make good money for a very limited outlay. Pamphlets of this sort offered far quicker returns than more substantial books, especially as most of the copies printed could usually be disseminated locally. One can easily see why publishers were so eager to feed an appetite for news whetted by the vast increase in the volume of cheap print during the Reformation. We will never really know how many of these news pamphlets appeared on the market in the course of the sixteenth century. These little works were intended to be read, passed around and then discarded. Many titles have no doubt disappeared altogether, so it is quite remarkable that some four thousand of these

German news-books have survived. This represents a substantial proportion of the total output of German books during the sixteenth century.

40

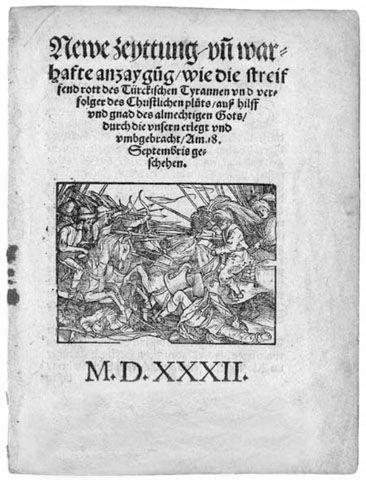

3.3 The

Neue Zeitung

. This is one of many examples that bring news of the war with the Ottoman Empire.

The news market, as one might expect, was strongest in the great commercial cities. Nuremberg, Augsburg, Strasbourg and Cologne were all established news hubs; but the predominance of these places was not absolute. The production of news pamphlets was remarkably dispersed, both around Germany and among the competing print shops of the major cities. It would be wrong to think that because pamphlets were cheap to produce, they were left to the smaller printing houses. Wealthier publishers were also keen to have a slice of this lucrative market, and in securing the latest texts they had a significant advantage. Many early news-books were based on letters or despatches addressed to the city magistrates. The city councillors were happy to see these reports placed in the hands of figures from the local printing establishment, who could be relied upon to publish sober, dispassionate and accurate versions, less likely to stir alarm and public agitation.

The overwhelming proportion of the

Neue Zeitungen

deal with high politics: usually, foreign affairs. The first surviving

Neue Zeitung

, of 1509, is a report of the Italian wars; the second, from 1510, reports the reconciliation of the French king and the Pope.

41

Over the century as a whole a large proportion of the news pamphlets published in Germany were devoted to chronicling the engagements and campaigns of the conflict with the Turks, on land and at sea.

42

The land war, in particular, was very close to home for the German city states; at various times the seemingly inexorable progress of Turkish arms threatened to envelop the eastern Habsburg kingdoms, markets in which the German merchants had important investments. Pamphlets that kept readers in touch with these events found an eager, if anxious audience.

This was by no means the whole of the news agenda. Printers also seized opportunities to share news of floods, earthquakes and destructive fires, celestial apparitions and notorious crimes. But these sorts of news events were not particularly common in the pamphlet literature. They found a more natural home in the ballad sheets and illustrated broadsheets that also play an increasing role in the news market of this period.

43

These were the genres of news sensations: in contrast the

Neue Zeitungen

were generally rather sober and restrained in tone. The title-pages took pains to emphasise that these reports came from authentic sources. Very often the title-pages declared that their text was ‘received from a trustworthy person’ or reproduced a letter sent from abroad ‘to a good friend in Germany’.

44

Sometimes they reproduced verbatim a despatch written by a captain from the camp or scene of battle.

45

In this way the news pamphlets invoked the trust that reposed in correspondence as a confidential medium between two persons of repute, to

bolster the credentials of publications that were now commercial and generally available. In keeping with these principles the news pamphlets are also generally careful to avoid any sensationalism. The titles are far more likely to emphasise that the despatch was ‘reliable’ or ‘trustworthy’ than shocking or astonishing. That sort of reporting was left to other parts of this increasingly sophisticated and diverse news market.

The market for news pamphlets was not confined to Germany. The Low Countries were another important news hub; a significant number of news pamphlets were also published in England, many of them, particularly in the last decades of the sixteenth century, verbatim translations of news from France or the Low Countries.

46

But news pamphlets were very much a phenomenon of northern Europe. It required really major events, such as the victory over the Turks at Lepanto in 1571, to stir Italian publishers to a significant output of news pamphlets; the Italian Peninsula, to this point the hub of the European news market, was in this respect beginning to diverge from the north European norm. The German pamphlets were unique in their success in establishing such clear brand identity. No other print tradition developed anything to match the

Neue Zeitungen

. These were the first publications in the new era of print to acknowledge on their title-pages that the bringing of news of current events was their primary purpose. They shared this news, often of faraway places and events, with a broad and expanding public – and at a modest price. They made possible the wide circulation of information that had previously only been available to a privileged few opinion-formers. In this respect alone the emergence of this new print genre represents an important moment in the development of a commercial market for news.

CHAPTER 4

State and Nation

T

HE

rulers of medieval Europe devoted much time and effort to making their wishes known to their subjects and fellow citizens. As we have seen, this became an important part of the information culture of the age. Decrees and ordinances were made known by public reading; trusted lieutenants were informed by letter. With the invention of printing much thought was naturally given to how the new technology could be applied to simplify this task. In the compact city states of Italy, such a use of print may have seemed superfluous. Most citizens could be made aware of changes in law or regulation by proclamations in the marketplace or citizen gatherings. The larger nation states faced a different problem. Here it was likely that different instructions would have to be drafted for the governors and sheriffs of the disparate provinces. It was the restless mind of Maximilian I that helped inspire the first sustained experiments in the use of print for official purposes. The year 1486 witnessed the publication of several texts celebrating Maximilian's election as King of the Romans (confirming that he would succeed his father Frederick III as Emperor). Printers in seven different German cities took part in the publicity campaign.

1

The press could serve the prince, but it could also bite. Maximilian received an object lesson in these dangers when, two years later, his attempt to impose his authority on his truculent subjects in the Netherlands ended in disaster. On 31 January 1488 he was stopped at the gates as he attempted to leave Bruges, and hustled away to the castle. There Maximilian was held until, under duress, he had conceded to the demands of the rebels. The humiliating treaty was promptly published in Ghent; only then was he released. Several gleeful accounts of his discomfiture were circulated in Germany.

2

The bruised but ever resilient Maximilian determined to make the printing press his own instrument. Over the next thirty years he made repeated use of print to

publicise treaties, new legislation, meetings of the German Diet, instructions to officials and the raising of taxes. Under his father, all of this would have had to be done by handwritten circular letters. Maximilian achieved not only greater efficiency but far greater public awareness of the workings of government.