The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself (13 page)

Read The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself Online

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

Despite these reverses many of the early enthusiasts kept faith. Pietro Martire d'Anghiera was an influential friend. His letter of November 1494 celebrating ‘this Columbus, discovered of a new world’ coined a usage that has remained current to this day. The term passed into general use, reinforced several years later when d'Anghiera published a highly influential account of the New World discoveries,

De orbis novo

. But the drama of the later voyages no longer had the same resonance in correspondence and print. In pragmatic mercantile circles the failure to discover the elusive western passage to Asia diminished interest in America. The news that the Portuguese had imported significant quantities of spice via the Cape route in 1499 and 1501 caused, as we have seen, far more turbulence in the financial and commodity markets.

22

In 1502 the exploration of the Brazilian coast by Amerigo Vespucci provided definite proof of the discovery of a new continental land mass. Vespucci was also a gifted self-publicist. His description of this voyage, undertaken in the service of Portugal, was quickly published in several languages and multiple editions.

23

Interestingly, this was the first of the great travel narratives to find a large resonance in Germany, where it was published in German translation in at least eight different cities. This suggests a telling contrast with the earlier Columbus expeditions. Discussion of the first oceanic voyages focused very much on their political implications, hence the particular interest they excited in Italy, where the Spanish Pope Alexander VI was heavily involved in resolving the resulting jurisdictional quarrel between Spain and Portugal. The Portuguese Crown, despite being first with the news of Columbus's extraordinary feat, made no attempt to publicise it: it was hardly in their interest to do so. Ferdinand and Isabella, and Pope Alexander in Rome, on the other hand, actively promoted publicity of the expedition's success. North of the Alps there was a curious lack of resonance, despite the success of Columbus's first account. Here there was a certain ambivalence towards Spanish ambitions, reinforced by the emerging Habsburg connection

with the Spanish Crown. The pronounced preference in France and Germany for news of Portuguese success (Portugal was a traditional French ally, as well as a counterweight to Spanish expansion) thus also has its political aspect.

Over the course of the sixteenth century publications about New World colonisation would multiply. As the full extent of the new Spanish possessions became clear, Europe's northern powers found themselves drawn inexorably into the unfolding Atlantic geopolitics. Taken on their own, the accounts of the first Columbus expedition provide an interesting snapshot of the news market at the end of the fifteenth century. To carry the first news to Spain and onwards to Italy, Columbus and his backers relied primarily on correspondence. In quantitative and qualitative terms this remained the most important and quickest form of super-regional news distribution. Correspondence provided precise, rapid information for those who needed to know. Letters had a limited distribution, but a high degree of reliability.

24

Print played a different role. Print allowed news to reach a broader public, those who could not expect to be in receipt of privileged information. Often what was presented as news was intended to serve the wider public debate that followed after significant events. This was the case with the publications that followed the fall of Negroponte (1470), one of the first news events to be widely discussed in print.

25

The disastrous loss of this key Venetian citadel in the eastern Mediterranean to the Turks provoked a flurry of print commentary, much of it in verse. But few readers of these works would have been learning the news for the first time. The plight of the garrison was well known, and news of their capitulation was swiftly disseminated from Venice around Italy, by letters and word of mouth. Here the publication of news pamphlets played a part in an acrimonious debate about political responsibility; they also allowed Italy's eager humanists to display their literary virtuosity on the subject of a contemporary tragedy.

At this early date print was a sporadic, occasional medium. It could not yet provide the constant flow of information necessary for those in positions of responsibility for whom critical decisions could depend on remaining fully informed. When Columbus arrived back from his first voyage, the full potential of print as a news medium was only just beginning to be recognised. That would await Europe's next resonant news event, the Protestant Reformation.

The Wittenberg Nightingale

There were many reasons why what became the Protestant Reformation should have come to nothing. Martin Luther was an unlikely revolutionary: a conservative middle-aged academic, who had made a distinguished career in the

Church. There seemed no reason for him not to esteem an institution that had nurtured and rewarded his talent; he certainly thought of himself as a devout Catholic. When his stubborn determination to hold to his controversial propositions on indulgences led him into irreconcilable confrontation with the church hierarchy, he found ranged against him the full might of Europe's most powerful institution. The Luther affair should have ended there, with the disgraced friar stripped of office and incarcerated, and quickly forgotten.

What saved Luther was publicity. When he formulated his ninety-five theses against indulgences, he sent copies to several potential disputation partners, including his local bishop, Albrecht, Elector of Mainz and Archbishop of Magdeburg. The theses soon found their way into print, and into the hands of a circle of interested intellectuals in Nuremberg and Augsburg.

26

From there news of Luther's angry denunciation of indulgences spread quickly around northern Europe. This was wholly unexpected. From any perspective Wittenberg, a small town tucked away in the northeastern reaches of the German Empire, was an unlikely focus for a major news event. Wittenberg was far removed from Germany's major communications network, and in the years that followed Luther would not always find it easy to keep up with the tidal wave of events unleashed by his protest. Both he and his friend Philip Melanchthon complained about the difficulty of getting news in Wittenberg.

27

If the papacy was slow to react, it was partly because the Church authorities in Rome could not conceive of anything of any significance emanating from such a backwater.

From the time that Luther's defiance became a public event, the torrent of publicity that accompanied each stage of the drama was quite unprecedented. News of Luther's developing critique of the Roman Church and the ominous steps taken to bring him to heel punctuate the correspondence of Europe's educated elite. Erasmus was fascinated by Luther, and initially inclined to sympathise with a man who seemed to share his withering contempt for some of the more debased and commercial aspects of the medieval Church.

28

But it was print that won Luther a wider audience, and ultimately ensured his survival. Luther made the first decisive move when he published – in German rather than the Latin of academic controversy – a sermon defending his criticism of indulgences.

29

By expanding debate beyond the closed circle of qualified theologians and engaging a wider public, Luther threw down the gauntlet to his Church critics. By 1518 he was Germany's most published author; by 1520–1, when the Pope finally pronounced his excommunication and the new Emperor Charles V endorsed this sentence, Luther was a publishing sensation. His writings were effecting a wholesale transformation at the heart of the European printing industry.

The Reformation was Europe's first mass-media news event. The quantity of books and pamphlets generated by interest in Luther's teaching was quite phenomenal. It has been estimated that between 1518 and 1526 something approaching eight million copies of religious tracts were placed on the market.

30

This was a very one-sided contest. Luther and his supporters were responsible for over 90 per cent of the works generated by the controversy.

The Reformation also provided a lifeline for a struggling industry. The bankruptcy of many of the first printers in the fifteenth century had brought about a substantial contraction in the numbers engaged in publishing printed books. By 1500 about two-thirds of Europe's books were being published in just a dozen cities, mostly major commercial centres like Venice, Augsburg and Paris. The industry was dominated by large firms with deep pockets, able to sustain the financial outlay (and raise the venture capital) to cope with the frequently long delays between publishing and selling large books. For the German publishers and booksellers who had previously struggled to make money from printed books, the Luther controversies offered a new way forward. For the books of the Reformation were different. Many of Luther's writings, and those of his supporters, were short. The vast proportion were published in German at a time when most books published for the international scholarly community were in Latin.

Short books, with a largely local market, which sold out quickly: these were the ideal product for small, less well capitalised print shops. As a result of the Reformation printing returned to, or was established for the first time in, over fifty German cities. Wittenberg itself became a major centre of print.

31

The Reformation was also responsible for substantial changes to the design of books, changes that would be highly influential in the subsequent production of news pamphlets. Much of this design innovation emanated from Wittenberg itself. Here again Luther was lucky. His patron, Frederick the Wise, had succeeded in attracting to the city Lucas Cranach, one of Europe's most distinguished painters. Cranach was not only a fine painter, he was also an exceptionally shrewd businessman.

32

He established both a busy painting workshop and a business for the production of woodcut blocks, used to illustrate some of Wittenberg's earliest publications (including, rather ironically in the light of Luther's later criticism of indulgences, a glossy catalogue of Frederick's relic collection). Although Cranach would cheerfully fulfil commissions for Catholic clients to the end of his life, he was an early and sincere supporter of Luther. His Wittenberg workshop was soon playing an important role in the promotion of Luther's cause.

It is to Cranach that we owe the iconic images of Luther that marked the stages of his career from idealistic preacher to mature patriarch.

33

Thanks to

the woodcut portraits taken from Cranach's sketches, Luther's was soon one of the best-known faces in Europe. Cranach's artfully presented portrait iconography of the solitary inspired man of God did much to build the mystique of Luther. In an age where few outside the ranks of the ruling classes would ever have had their portrait taken, this gave Luther a celebrity status that greatly enhanced his aura. It was as a celebrity that Luther was greeted and mobbed as he made his way through Germany to face the Emperor at the Diet of Worms in 1521. It was because Luther was a celebrity that the Emperor could not follow the private advice of his advisors, and deal with Luther as the Council of Constance had dealt with Jan Huss: that is, withdraw his safe conduct, arrest and execute the heretic.

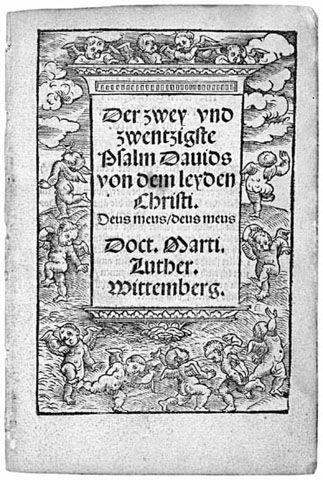

Safely back in Wittenberg, Luther continued a frantic regime of writing, preaching and publishing. The work was shared around Wittenberg's growing band of publishers who, with the benefit of Cranach's woodcuts, achieved a remarkable degree of design coherence. All the Reformation pamphlets, or

Flugschriften

as they were called, were produced in the convenient quarto format (about 20 by 8 centimetres) used for most short works at the time. They were often as few as eight pages long, and seldom more than twenty. In the first years these pamphlets were austere and functional, but as Luther's fame spread, Germany's printers exploited their greatest asset with increasing confidence. Luther's name was carefully separated from the main title on the front: the title-page text was wrapped in an ornate woodcut frame. This was the major design contribution of Lucas Cranach's workshop, and it became the distinctive livery of the Wittenberg

Flugschriften

.

34

It served as a visual marker that would identify Luther's publications on a bookseller's stall. Many of Cranach's designs were eye-catchingly beautiful: works of art in miniature to honour the words of the man of God. The success of the Reformation pamphlets also helped printers and booksellers appreciate the commercial benefit of brand identity, a significant step towards the development of serial publication. Customers responded by binding the pamphlets together in an impromptu anthology, which is how many have survived today.

The

Neue Zeitung

In the field of communication the Reformation was remarkable for a number of features, each in its own way a first: the manner in which a theological quarrel became a political event; the speed with which Luther attracted the support of a broad public; and the enthusiasm with which the printing industry exploited a commercial opportunity. In the outcome, the consequences for

the publishing industry were almost as profound as they were for the Western Church.