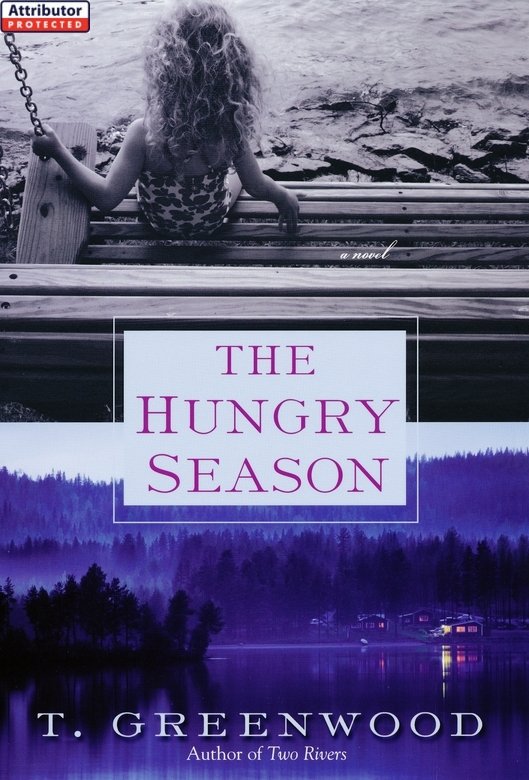

The Hungry Season

Authors: T. Greenwood

B

OOKS BY

T. G

REENWOOD

OOKS BY

T. G

REENWOOD

Two Rivers

Undressing the Moon

Nearer Than the Sky

Breathing Water

THE

H

UNGRY

S

EASON

H

UNGRY

S

EASON

T. GREENWOOD

KENSINGTON BOOKS

http://www.kensingtonbooks.com

http://www.kensingtonbooks.com

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

For my beautiful family

Hunger cannot be ignored ...

You cannot live without hunger.

Hunger begins your exchange with the world.

You cannot live without hunger.

Hunger begins your exchange with the world.

—From

Hunger: An Unnatural History

by

S

HARMAN

A

PT

R

USSELL

Hunger: An Unnatural History

by

S

HARMAN

A

PT

R

USSELL

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thank you first to Beya Thayer, who helped me survive that NaNoWriMo November and get through to the

first

end.To Vas Pournaras, Maria Mechelis, and Alexis Katchuk for helping me get the details right.To Henry Dunow, Peter Senftleben, and everyone at Kensington for their continued and tireless championing of my work. And to my family, who sacrificed so much so that this family’s story could be told.

first

end.To Vas Pournaras, Maria Mechelis, and Alexis Katchuk for helping me get the details right.To Henry Dunow, Peter Senftleben, and everyone at Kensington for their continued and tireless championing of my work. And to my family, who sacrificed so much so that this family’s story could be told.

In addition to the books mentioned in my notes, I am indebted to Todd Tucker for his book,

The Great Starvation Experiment,

and to Sam Shepard for his powerful and haunting play,

Fool for Love

.

The Great Starvation Experiment,

and to Sam Shepard for his powerful and haunting play,

Fool for Love

.

Lastly, I am tremendously grateful to the Maryland State Arts Council for their financial support of this project.

B

EFORE

.

EFORE

.

O

nce. Not that long ago, Sam believed that they would always be happy. That they had found the secret, stumbled upon it by accident perhaps. Or maybe they had done something to earn it. Regardless, they had found what had managed to elude everyone else: all those miserable bickering families, the ones they saw and pitied (the couples who love each other but not their children, the ones who love their children but not each other).

Happiness

. They had this. He was full of it, smug with it, bloated and busting at the seams with it. He basked in it, in the cool softness of it, thanked his lucky stars for it. But what he didn’t understand (or couldn’t, not then) is that everything is precarious. That even the sweetest breezes can change directions, that not even the moon is constant.

nce. Not that long ago, Sam believed that they would always be happy. That they had found the secret, stumbled upon it by accident perhaps. Or maybe they had done something to earn it. Regardless, they had found what had managed to elude everyone else: all those miserable bickering families, the ones they saw and pitied (the couples who love each other but not their children, the ones who love their children but not each other).

Happiness

. They had this. He was full of it, smug with it, bloated and busting at the seams with it. He basked in it, in the cool softness of it, thanked his lucky stars for it. But what he didn’t understand (or couldn’t, not then) is that everything is precarious. That even the sweetest breezes can change directions, that not even the moon is constant.

Here they are before:

Early summer evening when everything was still possible, Mena was in the kitchen of the rented cottage, washing lettuce from their summer garden. Sam could see her from where he sat in a wooden chair in the yard. The light from the window made a frame around her. She was standing at the sink, running water over the green leaves, her hands working. She caught his eye, smiled. Held his gaze until he blew her a kiss. Through the open screen door, he could smell dinner. Something Greek; there would be olives in a chipped porcelain bowl from the cupboard. Soft cheese.Warm bread. Franny would save the olive pits on a wet paper towel, bury them in the garden with her small fingers, hoping to grow an olive tree by morning.

Finn was down at the water’s edge, ankle deep in the lake, his naked chest white in the half-light. He had a red plastic bucket for the polliwogs. He was soundless in this task. Single-minded and intent. In the morning, Sam would go into town and get him a fishbowl. Most of them would die, but one or two might grow legs, eyes bulging. Franny was swinging in the tire swing that hung from the giant maple tree near the edge of the woods. She leaned backward, and her long curls spilled onto the ground. She had also abandoned her clothes in this rare June heat. They were six. It was twilight, and everything was possible.

Sam was thinking, of course, about the words that might capture this. Words were the way that he tethered the world, kept it close. Mena didn’t understand this need to articulate a moment, all moments. To convey

moonlight, water, hair kissing the ground

. She didn’t understand this inclination, this necessity, to render everything in prose.

Just eat,

she said. But Sam could not just eat. First, he needed to classify:

casseri, calamata, ouso.

moonlight, water, hair kissing the ground

. She didn’t understand this inclination, this necessity, to render everything in prose.

Just eat,

she said. But Sam could not just eat. First, he needed to classify:

casseri, calamata, ouso.

They sat at the rickety picnic table Mena had covered with a batik cloth that smelled of mothballs, of cedar. She lit the tea lights with a pack of matches she pulled from her back pocket. When she bent over to light them, he could see the soft swell of her breasts pushing against the edges of her tank top.

No peeking.

She smiled.

She smiled.

Aidani,

he thought, skin like wine, contained but threatening to spill.

he thought, skin like wine, contained but threatening to spill.

Olives!

she said, and Franny came running. Sam intercepted, picking her up and swinging her around until they were both dizzy.

she said, and Franny came running. Sam intercepted, picking her up and swinging her around until they were both dizzy.

Daddy,

she said. The best word of all.

she said. The best word of all.

Finn joined them reluctantly, holding the bucket with both hands, plastic handle and skinny arms straining with the weight of lake water and tadpoles. The water sloshed onto the grass at his feet, and it took all his strength to set the bucket down on the table next to the moussaka.

Mena:

tsk, tsk,

and she lifted the bucket, examining its contents before lowering it gently to the ground. Inside, the tadpoles swam blindly in dark water, bumping into the edges.

tsk, tsk,

and she lifted the bucket, examining its contents before lowering it gently to the ground. Inside, the tadpoles swam blindly in dark water, bumping into the edges.

They ate. Red tomatoes, purple eggplant, black pepper and lamb. They drank wine; Franny and Finn had their own small glasses, jelly jars, which they clanked together so hard you’d think everything would shatter.

Their voices, tinkling like glass, were the only ones here. It was the beginning of the summer, dusk, and the lake was theirs. They had been coming here, to Gormlaith, every summer since even before the twins were born. This is where Sam grew up. Home. Nestled in the northeastern corner of Vermont, on the opposite side of the earth from where they spent the rest of the year, it was a secret summer place. Undiscovered, for now.Theirs.

After dinner, the wine was gone. Finn had abandoned the polliwogs in favor of fireflies that flickered intermittently, teasing, in the hedges surrounding the house. Mena brought him a glass jar, the lid riddled with nail holes. He caught them easily with his clumsy little hands; they were more sluggish than you would think. Sam remembered this from his own childhood: the easy capture, the thickness of wings and the flickers of light. Finn was like Sam; he understood the need to contain things.

Franny twirled on tippy-toes, her bare feet barely touching the grass, her arms outstretched. Her ribs made a small protective cage around her heart, which Sam imagined he could see beating through her translucent skin, that miraculously transparent flesh of childhood that reveals every pulse and the very movement of blood. She spun and spun and spun and then collapsed on the grass, laughing, examining the twirling sky above her.

Mena sat down next to Sam in the other Adirondack chair, facing the water. Franny came to her, still naked, but cold now that the sun had set. Mena offered Franny a sip of her hot Greek coffee—

vari glykos,

very sweet

—

before placing the cup where it wouldn’t spill. She pulled Franny into her lap, enclosed her with her arms. Sam watched as Mena’s fingers wound in and out of Franny’s curls, listened as Mena hummed along with the music that wound

its

fingers through the night. Chet Baker crooned. Bullfrogs croaked and groaned. Crickets complained.

vari glykos,

very sweet

—

before placing the cup where it wouldn’t spill. She pulled Franny into her lap, enclosed her with her arms. Sam watched as Mena’s fingers wound in and out of Franny’s curls, listened as Mena hummed along with the music that wound

its

fingers through the night. Chet Baker crooned. Bullfrogs croaked and groaned. Crickets complained.

There must be a word for this,

he thought. It was on the tip of his tongue. He struggled, but it wouldn’t come. A sort of panic buzzed as he reached for it. Without the word, he was almost certain he would lose this. The lid would open, the fireflies escape. The bucket would spill, and the polliwogs would swim through the grass.

he thought. It was on the tip of his tongue. He struggled, but it wouldn’t come. A sort of panic buzzed as he reached for it. Without the word, he was almost certain he would lose this. The lid would open, the fireflies escape. The bucket would spill, and the polliwogs would swim through the grass.

Finally, it came.

Storg

,

,

he remembered. Mena once gave him the Greek words for love.Whispered them each, her breath hot in his ear:

agap

, er

, er

s, philia, storg

s, philia, storg

.

.

A gift.

Storg

.

.

And so, for now, everything was safe.

Storg

,

,he remembered. Mena once gave him the Greek words for love.Whispered them each, her breath hot in his ear:

agap

, er

, er s, philia, storg

s, philia, storg .

.A gift.

Storg

.

.And so, for now, everything was safe.

Other books

Mad Delights by Beth D. Carter

The Shark Mutiny by Patrick Robinson

Up Your Score by Larry Berger & Michael Colton, Michael Colton, Manek Mistry, Paul Rossi, Workman Publishing

Emerald Fire by Monica McCabe

Pines by Crouch, Blake

Naughty Girl by Metal, Scarlett

The Wild One by Melinda Metz

Rescuing Regina by Lee Savino

Too Much Temptation by Lori Foster

Biggins by Christopher Biggins