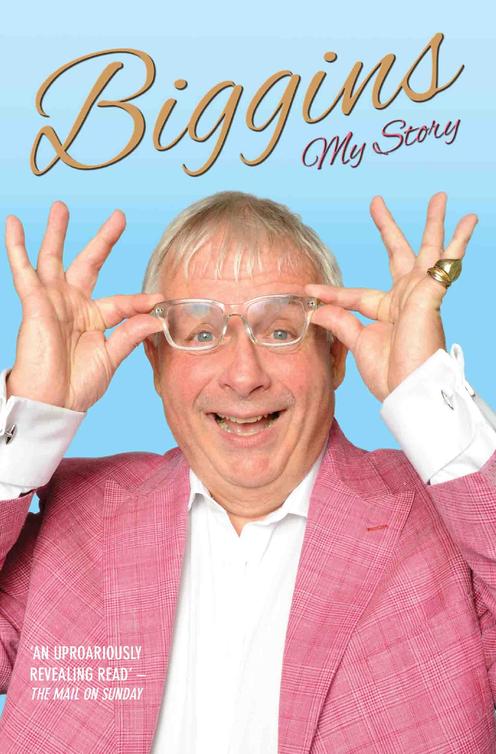

Biggins

Authors: Christopher Biggins

To my parents, Pam and Bill;

and to Neil Sinclair

Thanks to Neil Simpson for his help with writing the book. Thanks also to Lesley Duff and Charlie Cox at Diamond Management.

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue –

Waiting and Worrying -

- 1

A Boy from Oldham - 2

Finding My Voice - 3

Stage School - 4

On the Boards - 5

The RSC - 6

Roman Holiday - 7

Living Large - 8

The Real Me - 9

Double Takes - 10

Panto Dames - 11

The Reverend Ossie Whitworth - 12

Hollywood – and Back - 13

East End Boy - 14

Oh, Puck – It’s Liza - 15

My Golden Girls - 16

The VAT Man – and Neil - 17

Men Behaving Badly - 18

Fabulous at 50 - 19

Back on Stage - 20

The Jungle – and Beyond - 21

The Big Party - 22

Sad Days - 23

Saying No! - 24

There’s Nothing Like Another Dame - 25

A Last Word for Cilla -

- Plates

- About the Author

- Copyright

F

ive men and five women face the cameras at the lavish Versace Hotel on Australia's Gold Coast. After just one day of luxury, they are divided into two groups, put in helicopters and boats, then led off into the jungle. It's November 2007, time for the latest series of

I'm A Celebrity⦠Get Me Out Of Here!

and these ten faces will soon be the most talked-about people in Britain.

I wasn't one of them.

I didn't even know who any of them were.

When Malcolm McLaren got cold feet â and Janice Dickinson and Lynne Franks had their first fabulous row â I was locked away in a sky-high suite in another, slightly less glitzy Australian hotel. I was in seclusion. No television. No internet. No newspapers and no phone calls home.

A charming assistant â or was she my jailer? â seemed to be outside my room at all times. She even vetted the

room-service staff, so I didn't get any clues about events in the jungle. I was going to be the surprise late arrival in that year's

I'm A Celebrity

. And I was absolutely terrified. In little over a year's time I would be 60. Why on earth had I agreed to spend up to three weeks sleeping in a hammock, showering in a stream and eating food from a bonfire? This was not the Biggins way.

Shame about that no-telephone rule. Good job I'd smuggled in a spare mobile. So for a few glorious moments I thought I might get some vital information from the UK. I rang my partner, Neil. âHas it started? Is it on? Who are the celebrities?' I asked, desperate for an idea of what might lie ahead of me.

âThere's a real monster of an American woman,' Neil told me. Who could that be?

âAnd then there's the girl fromâ¦'

There was a loud, angry knock on my door. My assistant had heard my whispered conversation. The mobile was confiscated, my knuckles were rapped and my last link to the outside world was removed. âThe girl from where?' I asked myself. And it would be a while before I found out the monster's name.

I gazed out over the golf course from my hotel suite for two long days and nights. By now I imagined that the other celebrities would all have bonded and be living happily in their camp. I wasn't sure they would want a late arrival. Would I be welcome? Would I know who anyone was?

The more I thought about the show the more I worried. And the more I was told about the jungle the worse it got. Dr Bob and his team certainly didn't sugar-coat the pill

when they came round to tell me about the hazards I might face. It was all poison this, bite that, danger the other. Looking back, I think I can see why Malcolm headed home. It's suddenly made very clear that this is no sanitised television studio. Serious things can happen.

âAre you ready?' my minder asks.

I'm smiling. âAs I'll ever be.'

And off we go for my one, very brief spell at the Versace. I do some photos, give some final interviews, then it's back into a blacked-out van for an hour and a half's drive to a grimy little motel in the middle of nowhere. As instructed, I've got my regulation three pairs of underwear and two pairs of swimming trunks, and I'm given the pack of other clothes that I'll have to wear from now on.

Â

It's very, very early in the morning, though I don't know the exact time. My watch has been taken from me, and the crew who lead me into the jungle have theirs covered with masking tape. The mind games have begun. No words are spoken. I follow when the crew indicate that I should. I stop when they hold up their hands. All I know is that it's prime time back in Britain and that I'm doing a live trial. The crew leave me behind a tree and after a few moments I hear familiar voices. Ant and Dec.

Then I hear something else.

The dulcet tones of one Ms Janice Dickinson.

When I'm told to, I leave the safety of my tree and walk in front of the cameras.

This is it. But what have I done? In the next few moments everything is hysterical and fabulous and terrifying in equal measure. I realise, in one moment of

absolute clarity, that I have given up all control of my life for the duration of the show.

I was on the

I'm A Celebrity

rollercoaster, the public could chuck me off at any moment and there was nothing I could do except be myself.

I hugged Janice, shook hands with Ant and Dec and took a very deep breath.

Would I be able to cope? What would the public think? Was I making the biggest mistake of my life?

I

t is fair to say that my earliest reviews weren’t good. ‘He won’t make old bones,’ pronounced my grandmother, looking down on the little lad in his mother’s arms. There was none of the traditional ‘Oh, what a beautiful baby’ messing around for good old Grannie Biggins. I’ve always been a straight talker. No prizes for guessing who I get it from.

And Grannie B wasn’t the only critic to think I was in for a very short run.

‘He’s so tiny he’ll be blown away in the wind when you take him home,’ the maternity nurses told my mother, perhaps a little too cheerfully for her liking. Then came the worst review of all. ‘If you don’t get your son out of Oldham, he’ll die,’ said the doctor. It’s hard to ignore a closure notice like that.

Like all bad reviews, it seemed a little unfair. Despite

the nurses’ comments, I was actually a pretty healthy weight – a decent 9lb, thank you very much. The problem was my constitution. I wasn’t strong. I had bronchitis, gastric problems and the staff seemed to think I was at risk of pneumonia.

‘It’s all the smoke in the air,’ the doctor explained after another examination. ‘His lungs are too weak to cope with it and he won’t ever be able to breathe around here. Isn’t there somewhere else you could go, at least for a while?’

That was all the encouragement my mother needed. She had been up north for less than a year. On balance she felt it had been a year too long. We made the move in January 1949, when I was just three weeks old. I was wrapped up in a big, soft nest of cotton wool and set down on the passenger seat of a huge Pickfords lorry.

‘We’re going south,’ said my mother with a very broad smile. South was her idea of civilisation. Oldham, it’s fair to say, was not. She had been happy enough to give it a go. But the initial signs hadn’t been good. The first time my father came home from work on his motorbike, his face had been so covered in black soot from all the cotton mills, the coal mines and the factories that she hadn’t recognised him. She likes to call herself a Hampshire hog. The Lowry lifestyle simply didn’t suit her.

She tells me she sang all the way down the old A6 when we left town that cold January day. All except for the bit of the journey where we knocked over a water hydrant and left a brand-new fountain in our wake. As an actor I’ve always known the value of making a big entrance. At three weeks old it was nice to have made such a spectacular exit.

Fortunately, my dad was more than happy to give up his job and start a new life down south. He was Oldham born and bred but he’d seen the world in the Royal Air Force, where he’d met my mum before being posted out in Africa. So he was prepared to see a bit more of England now he had a sickly little lad to consider as well.

Our removal van dropped us off in the gloriously beautiful town of Salisbury. I always joked that I didn’t need to be in a Merchant Ivory film (though it might have been nice to be asked). Instead I got to grow up in one. The buildings are picture-postcard perfect. We had the river, the cathedral, the parks, the half-timbered houses, you name it. Trouble was, beautiful surroundings don’t pay the bills – a lesson I would need to learn and relearn many times in the years ahead. Nor did the fresh southern air solve all my medical issues overnight.

The first problem was that I had proved to be allergic to cotton wool. So being wrapped up in the stuff for half a day on the journey south hadn’t been a great idea. It took quite a while for those rashes to pass, Mum says. And I still come out in blotches if I touch the stuff.

And while the doctors in Salisbury weren’t quite as negative as the ones up at Boundary Park Hospital in Oldham, they too thought I needed a lot of work. My main doctor was a man who became a dear friend of the family. Dr Jim Drummond visited us up to three times a day when I was at my weakest, and he saw all of us through a lot of tough times. He helped me build up my strength and let my lungs develop at their own pace. It’s probably because of him that I

have

made old bones.

Mum and Dad had met in the sergeants’ mess at RAF Colerne near Bath in 1943. My dad, Bill, was a Leading Aircraft Man or LAC, while my mum, Pam, was a Leading Aircraft Woman or LACW. I remember seeing photos of them, proud and young in their forces uniforms. Back then the world was a frightening place. If you found love, you grasped it fast in case the war snatched it away from you. So, when something clicked at RAF Colerne, my parents didn’t hang around. They were married in St Paul’s church in Salisbury within three months of meeting. But wartime love affairs weren’t easy. They tried to have a honeymoon – though going to a home for retired priests in Fleetwood hardly sounds the most romantic of destinations. And the holiday was interrupted by my father’s call-up, which may well have been for the best.

Dad was sent out to Africa. Mum stayed in the forces on the home front, but, although they were both demobbed in 1946, they were left half a world apart. My mother headed back to Salisbury to look for work, and Dad was left nursing an injury in Cape Town while he waited for a space on a boat that could bring him home. Or would a boat take Mum out to him instead? Servicemen could take their wives out to Africa for £100 and get leave to stay for 12 months to see if they liked it. Dad could easily have got a job in a garage out in the sunshine of the Cape but my mother said no. If only she had known that the alternative to Cape Town would ultimately be Oldham.

They moved north for one simple reason: to find work. The krugerrands my father had brought back with him didn’t last long. And his first job, in a post office in Southampton, wasn’t for him. So after less than a year

they were on the road. Dad was going to work at Middleton Motors in his native Oldham. My mother was going to have a baby. Everything was going to change.

I was born on 16 December 1948. It was just three years after the end of the war and the country was still coming to terms with how tough victory would be. Mum and Dad were grafters. They didn’t take charity. But, like everyone, they struggled. The ups and down that have always been a feature of my life were already a feature of theirs.

When we arrived back in Salisbury, we were doing well. We moved into a tiny flat above a tailor’s shop. It was perfect because all we had were a few borrowed pieces of furniture from Mum’s family. But even that got lost when a fire in the shop spread upstairs.

Our next stop should have been better. We had a house – Mum’s parents’ old home – on Devizes Road on the edge of town. But it looked to have been a leap too far. Mum and Dad both worked all hours: Mum in hotels and bars, Dad in garages and petrol stations. But it was never enough to keep up the payments, so after a couple of years we moved out of there as well.

This time the three of us were going down the housing ladder. We moved out of town and into a caravan propped up on bricks in the corner of a muddy farmyard. It was a cold, crowded place and we stayed for two cold and crowded years. I don’t remember a lot of it – though putting my hand on a red-hot electric grill and saying, ‘Is this on?’ seems to stand out. My hand bubbled up like an omelette and out came the dreaded cotton wool to patch it up and make a bad job even worse. Outside the van I

also remember finding a rat trap. But looking at it wasn’t enough. I had to put my hand in it, to see what it did. ‘It traps you, Biggins, it traps you.’ One of the farm workers heard the screams and rushed over to help release the spring. To this day my fingers don’t quite sit straight.

Self-inflicted injuries apart, the time we spent in that caravan did teach me some pretty important lessons. One was that you can never expect your life to run in a straight line. Another was that life is what you make it. Living in a caravan with a small child is no party. But Mum and Dad did at least try to keep up appearances. Our caravan was clean and we certainly didn’t starve. We made the most of what we had. We survived.

I learned how to put on a show in that draughty old caravan. My mum taught me. I watched her get ready for work at a clothes shop in town and at the High Post Hotel just on the outskirts. She got into character for each role. Every day she put on the performance of her life. She was a glamorous, sparkling woman. Money and make-up were still pretty scarce in the early 1950s. But when my mum was serving behind her counters you would never have known she had got ready in a caravan. She dressed well and knew how to charm the customers. Showbusiness is all about smoke and mirrors, painting on a smile and carrying on with the show. I learned that early. I had a feeling I would end up being pretty good at it.

Dad’s lessons were just as important. He simply never gives up. When his garage work didn’t bring in enough cash during the week, he manned petrol pumps at another one at the weekend. When the River Avon rose six feet, burst its

banks, flooded his first premises and destroyed most of his equipment, he just started all over again. And he put on a performance as well. He’s the best salesman I know. He can talk the hind legs off a donkey and win jobs with charm alone. That’s another useful skill in showbusiness.

‘Christopher, I need you to help me pack. We’re moving.’ Mum’s smile was as wide as I had ever seen it. Dad’s was just as broad. It was 1953 and we were heading back into Salisbury, to a two-up, two-down house backing on to the railway line on Sidney Street. It’s a stretch to say the good times were going to roll. But we were certainly on the up.

Having people my own age around was a revelation in our new home – in fact, having any neighbours at all was a little different after the farmyard. But I wasn’t actually that keen on all the other kids. I think I was already getting to like being the centre of attention. Sharing the limelight with other children was never going to be my thing. So I didn’t mix that well during our first few years back in town. Mum remembers me playing with the rest of the so-called Sidney Street gang, but I only really remember playing with one of the kids from the newsagents’ shop opposite, Noyce & Sons. Kay, the owners’ daughter, was that one early pal. We played Doctors and Nurses, the way you do. That’s when I discovered the female form, though strictly as an observer.

Where I did have fun was Southampton with my other grandparents. Lil and Jack Parsons had a little flat there and I was always desperate to visit. Lil was very theatrical, which I already loved. She was always singing and she could play the piano by ear. She also gave me my first taste

of real theatre. She had a huge extended family and one of her brothers was a leading light in amateur dramatics. I never got the chance to see him in a play – at this point I’d never even been inside a village hall, let alone a theatre. But I listened when he talked about his rehearsals and performances. It all sounded so thrilling, so magical. I wanted some of that excitement to rub off on me. So, while Grannie cooked a meal and Granddad sat around in his long johns and vest chain-smoking untipped cigarettes, I set up my own little fantasy world.

I would hang a sheet up in my bedroom to look like a theatre curtain. And I would put on little shows for the Southampton branch of the family.

Back in Salisbury our family’s only other very loose link with the entertainment world was a friendship with the Neagles, a trio who sang on cruise ships and had moved to Florida before I had even met them. Dad missed them and didn’t just talk about them all the time – he tried to talk like them as well. The head of the Neagle family had given him a Star of David as a keepsake. So Dad put on a cod-Jewish voice that made me laugh and drove Mum mad. ‘I don’t know what he’s talking about. He’s not even circumcised,’ she said after one particularly long impression.

‘I won’t take my coat off. I’m not stopping.’ That’s what Grannie B would always say when she arrived from Oldham. Then she would stay for weeks. Sidney Street always seemed to be crowded. Yes, it was a lot bigger than the caravan. But it wasn’t exactly a palace. We had an outside toilet – everyone did back then. And our toilet was

never empty. We had a very big resident spider. I was terrified, quite terrified, of spiders back then, which meant going to the toilet as a boy was all a bit of a nightmare. Now, after the jungle, I have learned to take both spiders and outside toilets in my stride.

Monday night was bath night on Sidney Street. Dad dragged out the standard-issue tin bath and Mum filled it up with water boiled up on the fire in the front room. Then I got in for my weekly wash. Now, having a bath in front of your parents is bad enough. But I had a bigger audience. Every Monday, every single one for around 16 years, my mum’s friend Maisie came round. The regularity of it drove Mum mad. The embarrassment of it nearly did the same to me.

Maisie’s husband Les would go out to the pub with my dad and she would settle down for the night as I got undressed and began my ablutions. Yes, I already liked having an audience and being the centre of attention. But this was ridiculous. Couldn’t Maisie arrive later or leave earlier? Did her visits always have to happen on a Monday? Some weeks when my bath water had been drained away, Mum would change into her nightdress and put her curlers in to try to persuade Maisie it was time to leave. But she never got the hint. I was so pleased when we finally had enough money to have an indoor bathroom put in. Maisie still came round every Monday night until I was well into my teens. But at least I was no longer the main attraction in the middle of the living-room floor.

Monday must have been one of my mum’s rare nights off. She had a new job in a cocktail bar at the Cathedral Hotel

on Milford Street in the middle of town. Today it’s a sad and tired-looking place. But in its heyday, in Mum’s day, the hotel and its main bar absolutely glittered. People dressed up to drink there. Nights out were few and far between, so everyone felt a sense of occasion when they enjoyed them. And the job could hardly have suited Mum more. She was so glamorous, so gregarious.

The place suited me just as well as it suited my mum. The hotel manager and his family lived upstairs and I would hang around with their daughter, Pam, while our parents worked. I think Pam and I were supposed to do our homework and play games. But we found something else. We discovered the wonder of room service. We rang down for whatever we wanted. Beans on toast. Strawberry milkshakes. Cheese sandwiches. A matter of minutes later, as if by magic, our orders would arrive. Men and women in uniform would bring them, on trays and trolleys, the white china plates covered in shiny silver domes and resting on starched white cloths. It was divine. And there was something else. Pam and I were kids. She was the manager’s daughter. So we never had to pay the bill. For many, many years I don’t think I realised that with room service there was a bill. The pattern of my life was already beginning to emerge.