The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (21 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

The eastern Roman domain was shrinking. Not drastically or all at once, but a little at a time. The Persians had chipped away at the eastern border. To the west, invasions of Bulgars and Slavs into Thracia were growing more persistent; so in 512, Anastasius decided to build a wall against them.

Wall-building against barbarians was an old and honorable solution: Hadrian’s wall in Britain was only one of many erected in an attempt to keep invaders out. But the building of a wall was also an admission of defeat. It divided land into civilized and uncivilized, Roman and barbarian, controlled and uncontrolled; and Anastasius’s wall, the Long Wall, gave Thracia away. It was fifty miles long and stood thirty miles west of the city. “It reaches from one shore to the other, like a strait,” wrote the sixth-century historian Evagrius, “making the city [of Constantinople] an island instead of a peninsula.”

14

The Long Wall saved Constantinople, but it temporarily reduced the Roman holdings west of Asia Minor to the capital itself and the land immediately around it. Despite the lingering threat of Persian attack, this reoriented the entire empire towards the east, away from the west. From this point on—with Italy lost to Theoderic and his Ostrogoths, the remnants of the western empire gone beyond recovery, growing hostility between the bishop of Rome and the bishop of Constantinople—the eastern Roman empire began its transformation into something slightly different: Byzantium, an empire that was less Roman than eastern, less Latin than Greek, and increasingly less

catholic

in the eyes of the bishop of Rome.

*

I

RONICALLY, WHILE

A

NASTASIUS

was building the Long Wall to protect his empire from barbarians on the outside, barbarism on the inside of the wall became a much greater threat.

Since the time of Constantine, the traditional Roman sport of gladiatorial combat had been systematically replaced by chariot-racing, which was not as closely associated with worship of the old Roman gods. In the larger cities of the eastern empire, chariot-racing dominated the sports and entertainment scene: like stock car racing in Charlotte, North Carolina, or hockey in Toronto, it was a citywide phenomenon, part of the background of daily life even for citizens who weren’t particularly involved in it. Everyone in a city the size of Constantinople knew who the star chariot-drivers were; everyone had at least a passing acquaintance with the race results; and a good percentage of the city’s inhabitants identified themselves, however loosely, with one of the chariot-racing teams.

These teams were not defined by individual drivers and their horses. Different associations and companies in the city sponsored the races, paying for horses and equipment, and each one of these sponsors used as its symbol a color: red, white, blue, green. A number of different horse-and-driver pairs might race under the color blue, and spectators of the races became fans, not of individual performers, but of the color under which they raced. The Blues were one group of fans, the Whites another; and like modern boosters, these fans (largely young men) were fanatical in their devotion to their color.

15

They also hated each other with a zeal that scholars have tried to explain by finding deeper reasons for the hostility: perhaps the Reds were aristocrats and the Whites were merchants; maybe the Greens were inclined to Chalcedonian Christianity, while the Blues preferred the heresies of monophysitism. None of these explanations really hold up. The fans hated each other irrationally, like soccer fans who beat each other senseless at half-time.

By the time Anastasius died of old age in 518, the fans had settled into two opposed factions: the Blues, who had absorbed the Reds, and the Greens, who now encompassed the Whites. They were increasingly violent, always ready to seize any excuse to murder fans in the other faction. In fact, three thousand Blues had been killed at Constantinople in a 501 riot over chariot-race results, and other riots in 507 and 515 had been almost as bloody.

16

Anastasius left no son, although he had nephews who were anxious to claim the right to rule. In their place, though, the imperial bodyguard elected its own commander, the seventy-year-old career army officer Justin, as the new emperor.

Justin was shrewd, experienced, and had the support of the Blues. He also had the firm support of his nephew Justinian, a soldier in his thirties. In 521, Justin made his nephew consul, the highest official position in Constantinople below that of emperor, and Justinian began to take a greater and greater part in the government of the empire.

He was a competent administrator and an accomplished military leader. But he was also an ardent Blues fanatic who did little to quell the growing violence of the racing fans in the city. Their excesses grew worse and worse. “They carried weapons at night quite openly,” writes Procopius, “while in the day time they concealed short two-edged swords along their thighs under their cloaks. They used to collect in gangs at nightfall and rob members of the upper class in the whole forum or in narrow lanes.” The people of Constantinople quit wearing gold belts or jewelry, since this was an open invitation to be mugged by a gang of Blues or Greens; they hurried home at sunset so they could be off the street before dark. It was a state of affairs that would persist for the next fifteen years before breaking out into open conflagration.

17

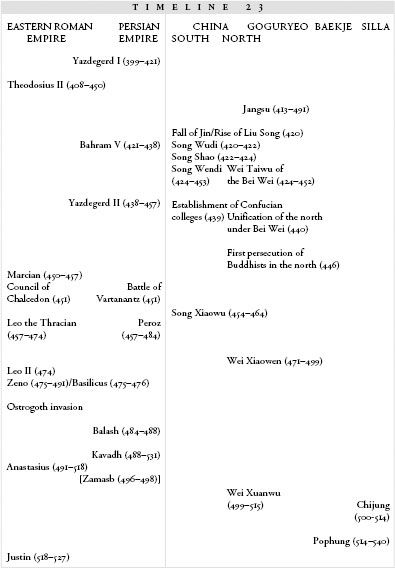

Between 471 and 527, the Bei Wei of the north expand to the south, while Goguryeo continues its conquests, and Silla moves carefully towards nationhood

T

HE

B

EI

W

EI

in the north of China were strong and warlike, the Liu Song in the south fading. Despite the imbalance, the two kingdoms had sworn a temporary truce. They had spent more time fighting over boundaries than figuring out how to strengthen their own states, and both needed to pay attention to neglected domestic matters. “Our ruling ancestors have worked hard to reign,” the Bei Wei emperor Wei Xiaowen remarked, “but to establish an internal norm was an uphill task.”

1

Wei Xiaowen was the great-great-grandson of the Taoist emperor Wei Taiwu, who had died barely twenty years before Wei Xiaowen’s coronation—an oddity produced by the fact that each of Wei Taiwu’s successors had begun fathering sons at the age of thirteen or fourteen. Wei Xiaowen himself was crowned in 471 at the age of four. At first he was under the control of his grandmother and regent, the dowager empress Feng, a woman who only had power because she had managed to defy the traditions of the Bei Wei. The ancient custom of the nomadic Tuoba clan, the not-so-distant ancestors of the Bei Wei royal family, decreed that the mother of each crown prince be put to death so that she could not influence the politics of the court; Feng, who was Chinese by blood, had maneuvered her way out of execution. She then exercised her considerable energy and ingenuity in order to gain as much power as possible, inadvertently proving the point of the bloodthirsty Bei Wei custom.

As her grandson grew, the two managed to work out a power-sharing arrangement that turned them into co-rulers. Together, they began to transform the Bei Wei court into a place that drew more and more from the Chinese heritage of the empress Feng, and more and more shunned the traditions of the Xianbei nomads who had originally formed the kingdom. Chinese officials gained high places in the government; no one was allowed to wear the traditional nomadic dress of the Xianbei; the two even outlawed any use of the Xianbei language, decreeing that only Chinese could be spoken, and forced the great families to adopt Chinese surnames in place of their traditional clan names.

2

Taoism remained a strong thread in the tapestry of northern Chinese religion; in fact, the peculiarly magical form of Taoism practiced by Wei Xiaowen’s great-great-grandfather, focused as it was on the preparing of elixirs (Wei Xiaowen himself had a court alchemist who spent many years trying to make the emperor a potion for immortality), was the bedrock on which medieval Chinese advances in pharmaceutical and chemical formulations were built.

3

But Confucianism and Buddhism provided the Bei Wei throne with much more useful tools for rule. As it had for centuries in China, Confucianism supplied a model for a state hierarchy; it provided a picture of the world in which properly ordered, properly structured government was an essential part of an orderly and moral universe.

Buddhism offered something else entirely: a model for kingship.

The Buddhism of northern China was Mahayana Buddhism, which (in contrast to the Theravada Buddhism of India and southern Asia) had developed a whole series of deities, each exercising a kind of kinglike power. These deities were not quite a pantheon. Rather, each one of them was Buddha in a different manifestation. These manifestations were called bodhisattvas; they were enlightened ones who had reached Nirvana and “release from the cycle of rebirth and suffering,” but who had chosen to turn back and remain in the world, refusing to depart into Nirvana until all were saved.

4

This was a departure from the intensely individual focus of Theravada Buddhism. Instead of simply honoring those who withdrew into solitude, Mahayana Buddhism praised those greater and more accomplished believers who worked on behalf of the less powerful. The bodhisattvas were the very models of kindly kings, and the Buddhism of the Bei Wei gave the emperor the power of ideology, the sanction of an entire system of doctrine to undergird his claim to extend a wise and benevolent rule over his people. Wei Xiaowen and his grandmother built lavish Buddhist temples, provided land and money, and stamped the imperial sanction firmly on the religion by commissioning enormous Buddhist sculptures to be carved right into the soaring cliffs near the northern Bei Wei capital of Pingcheng.

5

Under their patronage, scores of Buddhist monks migrated from the south and west into the Bei Wei kingdom, and Buddhist monasteries sprang up all through the country. One of the most famous of these, the Shaolin Monastery on the sacred mountain Song Shan, was established by the Indian monk Batuo; the monks of the monastery were bound, by the terms of their royal endowment, to pray for the emperor and for the peace of the Bei Wei people. As part of their prayer and meditation, the monks followed a set of physical exercises intended to focus the mind. According to legend, Bei Wei generals who visited the monastery saw the monks carrying out their exercises, recognized the value of the systematic movements for fighting, and adopted them. These movements are considered the source for the martial art of kung fu.

6

In 490, the dowager empress died, leaving Wei Xiaowen, at twenty-three, in sole power. He observed three full years of mourning for her—the traditional period of grief for a mother, not a grandmother (who typically got twenty-seven days).

7

With the mourning over, he rounded up the clan leaders of the Bei Wei—now doubling as court aristocrats with Chinese names—and led them on what he claimed would be a military reconnaissance into southern China. Instead, he halted the party at the ruins of Luoyang, the old Jin capital that had been starved and sacked into submission in 311. “Pingcheng,” he told his men, “is a place from which to wage war, not one from which civilized rule can come.” Luoyang, five hundred miles farther to the south, was the pinnacle of his plan to turn the Bei Wei into a fully Chinese kingdom. He intended to rebuild it and to move the entire government from the old capital of Pingcheng; and he planned to recarve the giant Buddhist sculptures on two cliffs overlooking the river that ran through Luoyang, so that the divine eyes would still be watching the new capital city.

8

The rebuilding took nine years, and Wei Xiaowen did not live to see it finished. He died of illness in 499, at the age of thirty-two, and was succeeded by his sixteen-year-old son, Wei Xuanwu. At its peak, the reconstructed city was home to over half a million people, with walls eighty feet thick protecting them and five hundred Buddhist monasteries inside. Only Chinese was spoken inside, and the Chinese classics had been gathered into a great city library for the education of the future officials of the Bei Wei. The ex-barbarians were coming closer and closer to eclipsing the glories of the Jin.

9

T

O THE EAST

, the little Korean kingdom of Baekje—worried about the swelling size and power of Goguryeo, to its north—sent an appeal to the Bei Wei court asking for protection and alliance.

10

The great Goguryeon king Guanggaeto the Expander had been followed by his son Jangsu, who ruled for seventy-nine years and earned himself the epithet “The Long-Lived.” For decades, Jangsu had been carefully transforming Goguryeo from a collection of conquered territories into a state.

Twenty years into his rule, he moved his capital city. His father had ruled from the ancient capital city of Guknaesong, on the Yalu river: it was a good and defensible place for a fortress, but with Goguryeo’s territory expanded so far down the peninsula, Guknaesong was now too far north to act as a center of government. Jangsu decided instead to rule from Pyongyang, farther south, on the broad plains of the Taedong river.

11

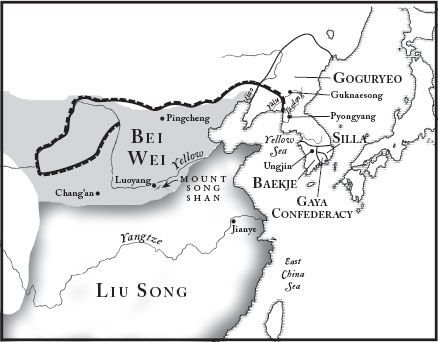

23.1: The East in the Era of King Jangsu

This suggested a new focus on the south and alarmed the two southern kingdoms of Silla and Baekje. Both realized that help would have to come from the northern Bei Wei; the Liu Song were no longer powerful enough to tip the balance of power.

Bei Wei armies were dispatched to help Baekje out, and Silla allied with its neighbor as well. But even this triple defense proved inadequate. In 475, King Jangsu of Goguryeo led his armies against the capital city of Baekje. He captured the king of Baekje in battle and beheaded him, and the remaining Baekje government was forced south to the city of Ungjin.

Baekje had almost been destroyed by the conflict. Meanwhile Goguryeo had expanded its borders to cover a massive territory stretching far up to the north and even over to the west.

But despite the ruination of its neighbor and ally, Silla survived. In part, this was because Goguryeo saw Baekje as a threat and Silla as an afterthought; Silla had lagged behind the other two states. In 500, when the Sillan ruler Chijung came to its throne, Silla still had little industry, almost no foreign trade, rudimentary administration. So unformed was its sense of nationhood that the country did not even have a single accepted name.

Chijung became the catalyst for Silla’s awakening as a nation. He took, for the first time, the Chinese title of king (

wang

) instead of the traditional title of

maripkan

, which was closer to “governing noble.” He began to outlaw some of the more ancient and unpleasant Sillan customs, such as burying slaves along with their masters. He brought Chinese consultants in to teach the people of Silla how to plow with oxen (something they had never done) and to demonstrate how to construct an underground ice-cellar to preserve food in the hot summer months.

12

Like the king of Bei Wei, the monarch of Silla saw Chinese government, Chinese technology, even Chinese dress and Chinese names as the keys to strength. With Chinese customs as his tool, he shaped Silla into a nation. His mythical stature as the father of Silla is preserved in the tales about him, which explain that Chijung had trouble finding a wife because his penis measured seventeen inches long.

13

Chijung’s successor, King Pophung, came to the throne in 514; under his direction, Silla’s government solidified into a true centralized state with a written code of law (published in 520) and a state religion. It was also during King Pophung’s rule that Buddhism finally came to Silla.

Baekje and Goguryeo had been Buddhist for over a hundred years, but in 527 Silla was still unconverted. In that year, the Indian monk Ado arrived in the capital city just in time to help the king of Silla out of an embarrassing dilemma. According to the traditional account

Haedong kosung chon

, the king of the Liu Song, in southern China, had sent an ambassador to Silla bringing gifts of incense, but neither the king nor his court knew what the incense was (or how to interpret the gift).

Ado, who was present in the court, explained that you were supposed to burn it, upon which the Chinese envoy bowed to him and said, “So monks are not strangers in this country after all.” Immediately, the story adds, King Pophung “issued a decree permitting the propagation of Buddhism.” Not long afterwards, Pophung went a step further and declared Buddhism to be the

state

religion. The story reveals, with unusual openness, a court full of barbarians who know their own shortcomings and are saved from humiliation in front of the infinitely more sophisticated Chinese ambassador.

14

The only way to prevent further humiliation was to become even more Chinese. Before long, the people of Silla had developed their own version of the past: Yes, Buddhism had come to Silla late, but Pophung claimed that royal builders, while excavating for new foundations, had uncovered Buddhist stupas from long ago and more: “pillar bases, stone niches, and steps,” remains of an ancient Buddhist monastery. He was refashioning the tale of Silla’s past: Buddhism had been part of its history for centuries, even longer than it had been a part of the history of the neighboring kingdoms. With a mythical past behind it, Silla was ready to give Goguryeo a run for control of the peninsula.

15