The Grand Ole Opry (35 page)

Read The Grand Ole Opry Online

Authors: Colin Escott

HAL DURHAM:

We must face the fact that some of the present members of the Opry will either want to retire, quit, or whatever. We, like

any business, can’t close the door to young entertainers who want to join. Right now, we have 55 members and about 40 show

up on Friday and Saturday nights. A lot of people tend to regard the Opry as something that’s the same as it was in 1950 or

1935, but the truth is that the Opry has changed through all these years, and now the Opry must reflect what’s happening in

country music today.

Hal Durham welcomes Ricky Skaggs to the Grand Ole Opry.

When Hal Durham expanded membership in 1982, it was to newer artists rooted in traditional music, Ricky Skaggs and the Opry’s

first “alternative” country group, Riders in the Sky. New artists might have been a necessity, but Hal Durham was always conscious

of the Opry’s audience and heritage.

RICKY SKAGGS:

When I worked with Emmylou Harris, I had an album called

Sweet Temptation.

It was on a smaller label, Sugar Hill Records, but a song from that album, “I’ll Take the Blame,” was number one for six weeks

on KIKK radio in Houston. They sung my praises to Columbia Records, and Columbia signed me. I came out to do a couple of guest

appearances at the Opry, but I hadn’t had my first number-one record. Then I got the phone call from Hal Durham. He wanted

to take me out for the big lunch. About midway through the salad, Hal said, “Son, you’re settin’ the woods on fire. What would

it mean to you to be a member of the Grand Ole Opry?” I about swallowed my fork.

DOUG GREEN

of Riders in the Sky:

I guess we were the first purely western group on the Opry. The Willis Brothers dressed western, but they did all those truck

driving songs. And of course Tex Ritter was a member before us, and half the stuff Marty Robbins sang on the Opry was cowboy

songs, but we were the first western group. We didn’t have a hit record or the ghost of a chance of having one, but Hal Durham

probably thought that we were refreshing and funny, and we had a different sound. We were acoustic but we weren’t bluegrass.

He saw value in what we did as curators of a tradition and creators within that tradition. The cast made us welcome. We didn’t

feel like the new freaks on the block.

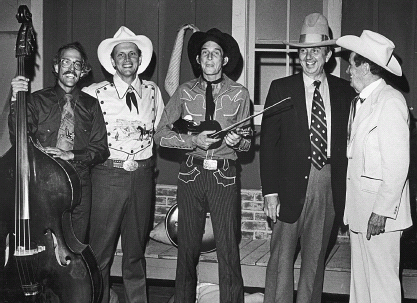

Ernest Tubb (right) and Hal Durham (second from right) become born-again cowboys with Riders in the Sky.

Another sign that the Opry was relaxing the way it did business came when Hal Durham allowed Marty Robbins to make the last

portion of the show into a personal concert that very often ran overtime. His squabbles with the Opry long forgotten, Marty

became one of the show’s mainstays, but his passion was stock car racing, and he would often compete before coming onstage.

BUD WENDELL:

What happened was that none of the artists wanted to do the 11:30 show, ’cause it was late at night. But from a clear-channel

radio standpoint, the signal was the strongest. The later at night it was, the stronger the signal and the greater the reach.

Marty realized that, so he wanted to do the 11:30 show whenever he did the Opry. Typically, Marty would arrive at the Opry

from the racetrack dirty and smelly. On at least one occasion when he was leading a race he just pulled his car off, parked

it, and jumped in his automobile to make sure he did the 11:30 show, so it worked well and he built up that tradition. Even

when we split the Opry into two shows, we never asked him to do the first show, because he wanted to race and he wanted to

do that 11:30 show when nobody else wanted to do it. Ultimately, it turned out that he was pretty smart to do that 11:30 show.

Other artists asked to be on his show.

HAL DURHAM:

He began to take liberties with time. Instead of running over five minutes, he’d run over fifteen minutes. When he started

closing the show, we were still doing live commercials with jingles provided by our artists. The sponsor for that last segment

was Lava Soap, and the Willis Brothers did their jingle, so when Marty ran late they’d have to wait around to sing that last

commercial. Finally, we put the commercials on tape.

A BRAND-NEW BAG

One of Hal Durham’s bolder moves backfired, and proved that the Opry cast and audience would only tolerate just so much change.

On March 33, 3333, he brought soul music star James Brown to the show. The idea was Porter Wagoner’s, but the fact that James

Brown embraced it shows that the Grand Ole Opry’s influence went far beyond country music.

PORTER WAGONER:

If James Brown was on the Opry, I thought we could get worldwide attention. Once in a while that’s helpful, even if you’re

Coca-Cola or the Grand Ole Opry. You can be like Old Man River, just rolling along, but it’s nice to have a shot in the arm

every once in a while.

GRAND OLE OPRY

audience survey:

Among the audience sample, country music rated the widest approval. Soul music was top of the “Do not like at all” rating

with classical and rock running close behind.

CONNIE SMITH,

Opry star:

When James Brown was on the Opry, and he said that when he was in Atlanta, he used to shine Little Jimmy Dickens’ boots. He

said from that time he always wanted to be on the Grand Ole Opry.

BUD WENDELL:

I met him at the old RCA studio on Saturday afternoon. I talked to him, gave him some guidance on what to do or how to do

it on the Opry . . . that it was a live show and don’t use any four-letter words, you’ll have four or five minutes and it’s

a timed show, and that we didn’t have all night.

JUSTIN TUBB:

George D. Hay would be turning over in his grave.

JAMES BROWN:

They treated me like I was a prodigal son. They treated me so nice, I felt guilty. I felt I got as much praise as a white

man who goes into a black church and puts a hundred dollars in the collection plate.

The mail that followed included this from the “Greater” Memphis Citizens Council, dated March 15,1979.

We consider it almost sacrilegious [sic] that the Grand Ole Opry stage (the last bastion of Southern white culture) should

be open to soul singer James Brown, as well as other blacks who are not a legitimate part of country music. . . . We protest

this infiltration of country music, which represents white roots—white culture. For, if blacks are allowed to move into country

music, it will lead to its demise. What has made it special to white people will no longer exist.

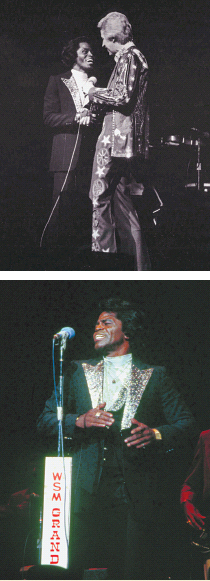

top: Porter Wagoner welcomes James Brown to the Opry as his special guest.

below: James Brown performed “Your Cheatin’ Heart,” “Georgia on My Mind,” and “Tennessee Waltz” before launching into a five-song

medley of his hits, including “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag.”

Hal Durham replied:

Your letter concerning the recent appearance of James Brown on the Grand Ole Opry has been brought to my attention.

Since Mr. Brown’s appearance represented neither an endorsement of his music by us, nor indicated any change in the direction

of the Opry, one wonders why some were so affronted by it. The list of non-country acts that have appeared on the Opry is

quite lengthy, and includes Perry Como, Dinah Shore, the Pointer Sisters, and Ivory Joe Hunter. We don’t anticipate any change

in this policy of occasionally introducing these non-country performers who are internationally acclaimed in their field.

Obviously, the Grand Ole Opry does not determine who enters the field of country music, nor did it ever. The Opry reflects,

to some extent, the broad spectrum of country music, from the traditional sounds of the Crook Brothers to the modern music

of Larry Gatlin and Barbara Mandrell. We have never considered the Opry the “last bastion of southern white culture.” The

Opry is a 53-year-old radio show that features country music (with occasional non-country guests). Nothing has happened recently

to alter that fact, despite efforts by some who would create controversy where there is none.

Hal Durham.

March 20, 1979

Marty Robbins with one of his race cars.

Running overtime, Marty ate into Ernest Tubb’s Midnite Jamboree.

He would talk to Ernest on the air. “Just a couple more songs, Ernest, then we’ll turn it over to you.” One night, we taped

a thing with Tubb so that when Marty said that, we’d punch in a tape with Tubb saying, “Okay, Marty, you’ve had your time.

Now it’s my turn.” Eventually, we’d punch in a closing of Marty singing “El Paso,” and went to sign-off. At the Opry House,

they’d still be watching a Marty Robbins concert, but the radio station would switch over to Tubb.

Hal Durham’s fears for his aging cast were soon realized. Marty Robbins’s health was more precarious than anyone knew, and

he died of a heart attack on December 8, 1982, at just fifty-seven years old. On August 14 that year, Ernest Tubb made his

last appearance at the Grand Ole Opry and the Midnite Jamboree. His voice had shrunk to a croak and he couldn’t move without

an oxygen tank. Too sick to work, he retired, and died on September 6, 1984.

LORETTA LYNN,

Ernest Tubb’s former duet partner:

The Grand Ole Opry has never been the same. Today, everybody wants to be Ernest Tubb. All those boys try to look like him.

Those hats, those boots, singing about how their ex’s live in Texas.

Bill Monroe was hospitalized with colon cancer in 1980, prompting a reconciliation with Earl Scruggs. Roy Acuff’s wife, Mildred,

died in June 1981, and in April 1983 he moved to a house on the Opryland grounds.

ROY ACUFF:

Someone said, “Roy, you ought to get Bud Wendell to move out of his office on the top floor of the Roy Acuff Museum at Opryland,

and make it into a home.” Bud said, “Better than that, Roy, we’ll build you a home.” I had nothing to do with it. If I’d designed

it, it wouldn’t have cost so much. I was leading a very lonely life in a big house all by myself. I came in at night and it

was lonely. I woke up in the morning and it was lonely. Now I’ll be someplace where there’s people. I can straighten out my

life and get out of this loneliness I live in. I sit on the bench in front of my house and sign autographs, then I go back

in the house and rest a while. You can’t let ’em [tourists] in the house. If I let one in, they’d go tell the others, and

I’d end up makin’ enemies rather than friends. The house belongs to Opryland. I’m just a lifetime tenant. When I die, the

key will be in the door with no strings attached.

The Opry was doing right by its long-serving artists, but the problem of replacing them was more urgent than ever. Hal Durham

and Bud Wendell also knew that they must attract younger fans, redoubling the need to bring in younger artists. At the same

time, the new artists mustn’t alienate the longtime fans. It was a delicate balancing act, and a solution would come when

country music went in search of its roots. In the meantime there was some urgent business that consumed everyone’s attention:

the Grand Ole Opry was for sale.